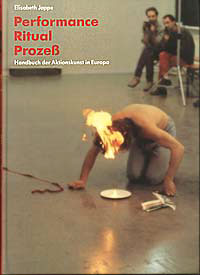

Elisabeth Jappe: Performance, Ritual, Prozess - Handbuch der Aktionskunst in Europa

Prestel-Verlag: München-New York, 1993

(book review)

Performance, Ritual, Prozess offers a brief survey of the European Performance Art

from the beginning to its current forms, with a special emphasis on the

performance of the seventies and eighties. The volume consists of four

units: the study, the "Protokolle", the artists´ interviews, and

the "Lexikon".

Performance, Ritual, Prozess offers a brief survey of the European Performance Art

from the beginning to its current forms, with a special emphasis on the

performance of the seventies and eighties. The volume consists of four

units: the study, the "Protokolle", the artists´ interviews, and

the "Lexikon".

This handbook written and compiled by Elisabeth Jappe is a useful tool for those who are conversant with the labyrinth of the European performance or for the adventuresome who are ready to set out for the unknown as they only wish to skip through either the quality colour photos that document the actions or through the entries of the "Lexikon" that present the artists briefly but to the point. The "Protokolle" or record of Performance Art displays 32 performances with the help of texts and photographs while the "Lexikon" or dictionary lists 160 performers, and they undoubtedly form the most precious part of the work. These depict the delicious pall-mall of the art of the sixties, seventies, and eighties in its complexity-a heterogeneity that defies systematization. Memories are the primary media of documentation, Jappe claims. The record does not intend to provide a systematical overview of all the various forms of performance, neither does it attempt to offer an art historical classification, nor an analysis or interpretation. Its purpose is to invoke the original emotional impact that the works had made on the audience, to grasp the passing and unreproducible. In the case of performance, however, which is a genre that is not concerned with the product but with the process that takes place in time, and with the aura created by the artist´s presence, the author´s goal might seem paradoxical but, at least, hardly attainable. Yet the record and the dictionary (the latter includes the artists´ biography, their method of work, and a description of a characteristic work), provide a rather tangible image of those non-recurrent events that are mainly to be documented by remembrance.

In this respect, the task of interpretation and art historical classification falls on the introductory study. Relying on the categories listed in the title of this volume (action, ritual, process), Jappe starts to construct a conceptual base which, if it had been applied consequently, could have served as a frame of reference for the interpretation of the matter at hand. Action as the expression of an idea or a world view in an act, the author says, is rooted in human culture. This act may be sacral like ritual or profane like the social critique of Diogenes who searched for a reasonable man with a lantern in his hands in Athens in broad daylight. Well then, Performance Art and performance in a narrow sense is ready to draw from ritual (the most prominent example to this might be Joseph Beuys) yet we should always be aware of the difference; while the form of ritual is essentially defined (it must be produced the same way every time), performance is never carried out as it was before. The notion of process has made its way into art through action painting and happening intending to attack the traditional idea which defined the aim of art as the creation of a product. Thus process is a method of art, a technique, which has become central with Expanded Performance. Process and ritual form two different aspects of Performance Art. On gaining new content, they are, from time to time, integrated into performance and enrich it with fresh meanings.

A promising start, as it is, is abruptly broken at this point. After two pages, the author throws away the frame of reference she has just constructed and embarks a new project. In the rest of her study, she cites data with great care and accuracy and makes them into a decent story of the evolution of Performance Art. She guides the reader from the romantic image of the artist at the turn of the century to the satire of Ubu Roi to the shift of paradigm in the art affected by the avant-garde to the revival of Performance Art in the trauma resulting from the II. World War, step by step. Then the antecedents and forerunners of performance are listed from John Cage to Yves Klein to Happening to Fluxus to Vienna Actionism, as well as artists and art forms that made a direct impact on performance, namely Joseph Beuys, Vito Acconi and Bruce Nauman, Body Art, Land Art, and Concept Art. The volume gives a detailed account of the difference between American and European performance, of the significance of "De Appel" in Amsterdam, which served as a meeting point for the non-official international art world from 1975 on, of female, social-political, and ritual performances, of the crisis of the eighties, of the expansion of performance, of its use of new materials, and of its relationship to media, and especially to video. Finally, it treats Spanish-Portugese and Eastern European performance (performance conceived under totalitarian regimes) in a separate chapter-including Hungarian works as well (those of Gábor Altorjay, Miklós Erdély, the Indigó Group, Tamás St Auby, Endre Tót, and Tibor Hajas). A performance by János Szirtes made in Fészek klub in 1988 and another by Böröcz-Révész called Hajnal (Dawn) is listed in the record, too. Unfortunately, Elisabeth Jappe leaves no space to interpret these works or put them in a context. For want of a better, I recommend a catalogue about these artists published by Artunion, Műcsarnok and Soros Foundation in 1988.

(Agnes Ivacs)