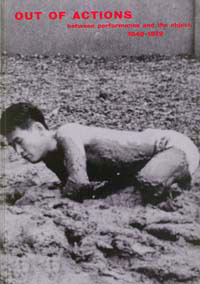

OUT OF ACTIONS: BETWEEN PERFORMANCE AND THE OBJECT, 1949-1979

Paul Schimmel (ed); with essays by: Guy Brett, Hubert Klocker, Shiniciro Osaki, Kristine Stiles, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles - Thames and Hudson,1998

(book review)

This

book was published on the occasion of the identically entitled exhibition

that was organized in Los Angeles this year (February - May1998) and was

on display in Vienna for almost three months from June on. The body of

the quasi-legendary photo-documents is accompanied by lengthy essays out

of which the first one, Leap Into The Void , presents a chronological

survey of the 30 years' production of the widely construed 'action art'.

(What is more, there is an exhaustive chronology of actions on the last

pages of the book.) 'Production' means the records of the actions as well

as the objects that came out of the actions (cf. the title!). Beside

the production, the essay deals with the circumstances (especially the

historical ones) that led to action as art form. According to this, the

changes in art and in the conception of art that occured in the fifties

can be traced back to the unprecedented horrors of the second world war

- such as Hiroshima and the Holocaust. These devastating events threw

light upon the fragility of creation and existence and, on the other hand,

the primacy of the act. As a projection of all this in art was the questioning

of the position of the art object (= a created object). More important

than that has become the process of creation. But not as an endevour

to produce something, rather as an action which evolves before an audience

and which incorporates time into art.

This

book was published on the occasion of the identically entitled exhibition

that was organized in Los Angeles this year (February - May1998) and was

on display in Vienna for almost three months from June on. The body of

the quasi-legendary photo-documents is accompanied by lengthy essays out

of which the first one, Leap Into The Void , presents a chronological

survey of the 30 years' production of the widely construed 'action art'.

(What is more, there is an exhaustive chronology of actions on the last

pages of the book.) 'Production' means the records of the actions as well

as the objects that came out of the actions (cf. the title!). Beside

the production, the essay deals with the circumstances (especially the

historical ones) that led to action as art form. According to this, the

changes in art and in the conception of art that occured in the fifties

can be traced back to the unprecedented horrors of the second world war

- such as Hiroshima and the Holocaust. These devastating events threw

light upon the fragility of creation and existence and, on the other hand,

the primacy of the act. As a projection of all this in art was the questioning

of the position of the art object (= a created object). More important

than that has become the process of creation. But not as an endevour

to produce something, rather as an action which evolves before an audience

and which incorporates time into art.

Within the wide-ranging chronology the Abstract Expressionists´ heroic gestures as well as the reductive tendencies of the Minimalists and the objectlessnes of Conceptual Art is discussed. The origins are Pollock, Cage, Fontana, and Shimamoto; when talking about them it would be difficult to separate the artist and his work, the art object and its making since here the subject of art became its own making. Pollock´s canvas, laid on the ground, was more of Òan arena in which to act than a space in which to reproduce" (Rosenberg). As a consequence, there is no lasting work of art that can be exhibited; but in return the record of the action and the residual objects that came out of the actions will operate almost the same way as the original actions. This way it will not be the art object but the person of the artist that the cultural fetish is made of. Fontana in Italy and Shimamoto in Japan, completely independently from one another, challenged in almost identical ways the claims of painting to create the illusion of 3-dimensional space on a 2-dimensional surface: they violated the canvas by puncturing it and cutting into it, thus creating, not only representing, real space. They also initiated tendencies that combine painting with spatial elements. (The artists of the Nouveau Réalism of the sixties, for example, made their assembleges out of everyday objects.) Cage, too, meant to eliminate the life / art opposition in his chance operated actions as well as in his happenings where he rejected the traditional performer / viewer hierarchy. This ever accepted Òcast" was again challenged by the activities of such artists and trends as Yoko Ono, George Brecht, the Gutai group and the Fluxus whose works are only completed by the participation of the viewer (who, fulfilling the artist´s instructions, advances to be a quasi-author) or whose works are to be experienced rather than passively observed. Audience participation becomes of even more importance in the happenings of the sixties when the viewer, upon entering the gallery, interacted with what he/ she found there: with objects and with simultaneous but independent actions. Performances of the seventies require the participation of the audience in a ruder and rougher way. They place the viewer in uncomfortable and provoking situations, or - as the performers engages more and more frequently in self-endangering actions - cast him/ her in the roll of the abetting eye-witness. The appearance of the human body as another "material" for art, and endangering it as another theme can be connected again with the brutal experiences of the XXth century. Such phenomena can be considered as reactions to the threatened status of existence and they assert the primacy of humans over inanimate things. - Explanations of this kind and placing the individual incidents in wider historical or philosophical context is not so much characteristic of the first text as of the following four. The first essay, admittedly, only attempts to provide a road map through the extensive material. This is why it makes no attempt at defining things, nor does it inquire into the difference between performance, happening or installation. It focuses on 'action' meaning a kind of artistic activity that is visual and performative at the same time. There is one sole definition of Happening which could be applied to describe installation as well: "participatory environments that incorporated a chaotic assemblage of fragments of daily life". The same elusiveness is reflected in using combination labels such as "performance or performative sculpture/ installation", "action collage", and "interactive or performative environment".

The following three essays discuss in theoretical depth the artists and movements introduced in Leap Into The Void; the material being divided according to geographical groupings. Action in Postwar Japan (written by Shinichiro Osaki ) focuses on the events that took place in Japan and underlines their independence from those in Europe. In The Gesture and the Object Hubert Clocker compares the North American and the European trends, concluding that those in Europe were more strongly influenced by the socio-political and historical context of the period and that action operated as a liberating gesture in this area. Guy Brett, author of Life Strategies, dwells on the work of artists commuting between Europe and Latin America. The very last essay, Uncorrupted Joy, does not focus on one particular geographical territory but it is perhaps the most thorough writing of the volume, with many sided action-analyses. It also asks the question why this kind of art sometimes feels boring and/ or intolerable. Beyond the obvious answer that bad performances - performances full of idiosyncratic allusions and ideological contents - are inevitably insignificant, Kristine Stiles is also up to draw the attention of the spectators accustomed to passivity by the instantly consumable show business to the crucial fact that good (action) art, too, require more than a single glance, one has to enter into a committed relationship with it. Or as H. Clocker put it very thoughtfully in his essay: "the aesthetisized object is, so to say, a test case for society's willingness to communicate".

(Beáta Hock)