Kassel, 18 June – Documenta 7

Kassel. Two Hungarian periodicals – Művészet [Art] and Mozgó Világ [World on the Move] – have published articles on the Documenta 7, Kassel exhibition, so there is enough information available about this event. What makes it still worthwhile to talk about Kassel is the open, stimulating and thought-provoking milieu experienced by those who arrived here for a breath of fresh air from the stagnant indifference of the Hungarian public art scene.

Approaching the exhibitions and other events by driving into the city from the Autobahn or walking from the train station was made very easy for motorists and pedestrians alike by a system of road signs especially set up for this purpose. There was a separate little pavilion at which you could sort through a maze of brochures and leaflets giving information about the other cultural events going on in the city, some of which were taking place within the framework of the Documenta Urbana series of events. Anyone was free to place an advertisement in the pavilion… Galleries, theatres, cinemas and individual artists advertised their own events. Quite a few events, exhibitions and actions were organised with the purpose of giving a voice to different opinions and thus functioned as a kind of criticism or counterpoint to Documenta.

It was simply a great feeling that in the first line of the descriptive little brochures that served as entrance tickets to the exhibitions it read that the arts manager of Documenta 7 was Rudi Fuchs. Perhaps other people didn’t even notice this but – having been accustomed to reading invitations to Hungarian arts events – we did. This was especially true when we read into the accounts and criticisms of Documenta, or, in a more positive light, if we watched the openly critical one-hour programme on German television on Documenta, Kassel. However, it turned out that the arts manager, Rudi Fuchs – similarly to his predecessor, Harald Szeemann and others before him – had his own idea about how the exhibition should be organised and what was perhaps the most surprising for us was that he was able to implement it with the help of a team he himself had formed (van Bruggen, Celant, Gachnang and Storck) even though at the time when the idea was being drafted a frenzied debate had broken out. Documenta = the art of today as Rudi Fuchs sees it. You can agree with him or can still have discussions and criticise him … because this was a real debate with real issues and participants. In Kassel the works were not selected by an anonymous jury, and the exhibition concept was not created by an unidentifiable, unaccountable and incompetent fine arts association or arts directorate like in Hungary.

Of course Documenta attracted artists and the general public… and what took place around the exhibitions, in Friedrichsplatz – the square in front of the Museum Fridericianum –, at other locations in the city, in galleries etc. was at least as interesting as the exhibition itself. Whoever walked around, stayed alert and observed all the gatherings large and small or who searched around watching like a hawk to gather every bit of paper that was lying on the ground could be a part of the several “unofficial” art events that were taking place.

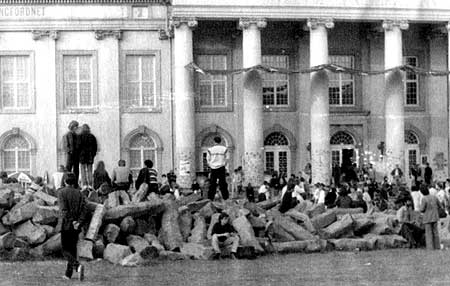

The work that caused the most controversy was Beuys’ 7,000 granite blocks and the tree planting action that went with it. This project was clearly aimed at the German citizen and not at the profession. Each one of 7,000 granite blocks transported to Friedrichsplatz was to be dug in the ground next to a freshly planted oak tree, so the more new oak trees were planted the fewer stones there would be left in the square. In a circular letter Beuys and the International Free University (FIU) invited the population to take part in the 7,000 oak tree event by buying and erecting one or more trees (at 500 DM a piece). Armed with the FIU stamp and Beuys’ signature the tree planters also got a “Tree Diploma” issued to their names. Beuys’ project attracted as least as many opponents as it did supporters. In the German television show about Documenta many happy tree owners declared what a good thing it was that artists were using their art to promote an issue (environmental protection) important for society.

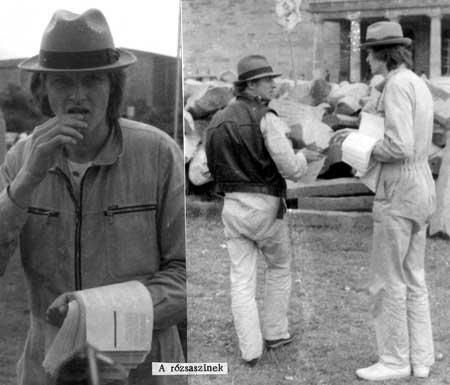

Other people regarded Beuys’ work as something that takes up a huge amount of money (mining the granite blocks and transporting them to Kassel) and one that would ruin one of Kassel’s most beautiful squares and architectural complexes for at least 11 years, and not just for the 2–3 years that Bueys believed it would. A group protesting against Beuys painted half of the granite blocks a ghastly pink the night before the Documenta opened. On the afternoon of the next day the same people dressed up in pink overalls and distributed their manifesto on Friedrichsplatz, in which they explained the reason for their action: they used the ghastly pink paint to ruin the square yet further in order to draw the public’s attention to their view that the pile of stones that would lie in front of the Fridericianum for 11 years would not draw praise for Kassel but rather serve as a mark of shame.

At the same time Beuys turned up next to the stones and a heated debate soon broke out between him and the public. Of course the stones didn’t stay pink for long: a clean-up team scoured off all the paint within three days using a high-pressure water jet.

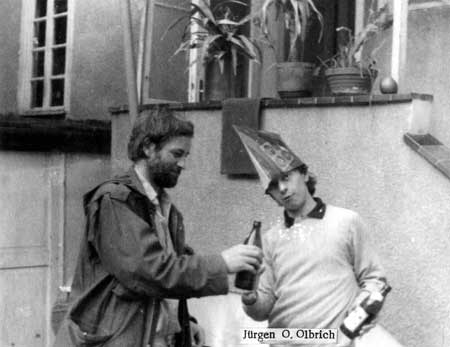

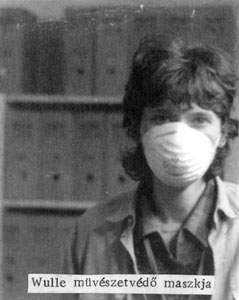

Simultaneously with Documenta, an event also called Documente (=documents) was going on for 100 days at an artistic space at Kunold Strasse 34, organised by Jürgen O. Olbrich. Each day of Documente – accompanied by a voluminous catalogue – featured a different artist each of whom was given the chance to present their art. The one hundred artists who participated included Ko de Jonge, Michael Gibbs, Janos Urban, Klaus Groh, Robert Rehfeldt, Wulle Konsumkunst, Klaus Staeck, Rod Summers, and others. Detailed archived documentation was available on every artist on the spot. The rooms of the house and the garden were filled with new exhibits every day. The presence of the artists made it possible for a huge number of cheerful, personal meetings to take place.

Jürgen Olbrich has been frantically organising arts events for years. Kunold Strasse 34 is the venue for regular performance art events and art actions. Jürgen organised several international competitions, either based on an invitation, such as the “Garden Exhibition” (1981), or on free participation, like the action called “In a Small Frame” (since 1980). In Kassel he is best known as an action artist. (Significant feedback was drawn by his one-week action called “I’m a Witness” and the exhibition that followed, calling attention to the fact that everybody is a witness to the events and changes around them and that indifference and the “it’s not in my backyard” attitude are no excuse and do not excuse anyone from their responsibilities.) His other works – mainly collages and assemblages – often provide social criticism. His activities mark out an alternative path as opposed to commercial, organised and official art.

Jürgen Olbrich’s house was the base for the artists and critics who arrived in Kassel from every part of the world for the 100 days of Documenta and Documente. This is where we met up with our American friends Buster Cleveland and Diana, who set off from Budapest to Kassel at the same time as we did – after two frantic days of work. (Before this they had spent about six months travelling around Italy funded by the money Buster had made from his collage exhibition in Brescia. It was from there that they had sent us a letter saying that they would like to visit us on their way to Kassel.) They arrived in the city a day before we did and by the time the exhibition opened they had plastered Cavellini stickers all around the venues.

We were sitting on Beuys’ stones, watching the crazy buzz in front of the Fridericianum and the floods of people coming in and out for days: a woman in a rusting mermaid costume made out of a green, blue, and pink foil-like material with a metallic lustre was walking about in front of the museum or majestically sitting on Beuys’ basalts. A man painted as a bronze statue set up his pedestal in various points of the square, positioned himself there and surveyed the sky motionlessly for hours with bronze coloured binoculars. Others made a giant ball of about three metres in diameter by wrapping ribbon around an aluminium tubular frame structure; they then left the completed ball on the square and the public rolled it all around for days after. A group of artists set up two Art Vending Machines at the entrance to the Fridericianum, where people could buy various individual works of art by 18 artists by inserting three DM. Beuys’ students at the Free International University set up two stands where all sorts of printed matter, photos autographed by Beuys and posters, etc. could be bought.

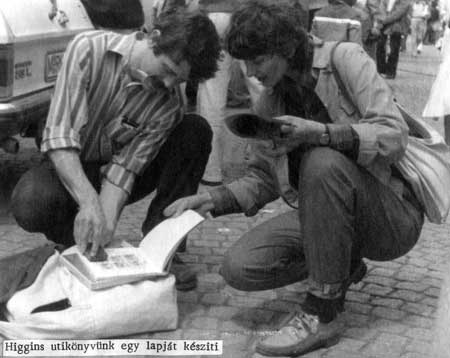

Turning up all at once in this bustle were the New York stamp artist, E.F. Higgins III, Pete Horobin from Scotland and Monty Cantsin (István Kántor) from Canada, the founder of Neoism, and Peter Below from Würzburg, who we had not been able to find on our way to Kassel the previous day, so we had left a message for him in the post box. It was just like a fairy tale because we only knew each one of them through correspondence. It turned out that they had arrived together for a day and had come from Würzburg, where a week-long First European Neoist Training Camp was to start the following day. (We would also have participated in the training camp if we had received the invitation that Below had posted months before or if he had got our letter in which we wrote that we were going… in any case, at that point we could not change our travel plans.)

Everybody had a lot to show the others so for the evening we agreed to meet up in the beer garden behind the Orangerie. This was Jürgen Olbrich’s and his friends’ regular haunt and Wulle Konsumkunst – whom we met a few days later in his studio in Cologne – also came here. Everyone was totally spaced out by this unexpected meeting!… Buster and Diana were full of praise for Hungary, and Monty Cantsin said that after the training camp he would be coming to Budapest and we could probably meet up… We started swapping stamps with Ed Higgins – he has some pretty amazing Xerox-stamps…

Since every member of our company took part in the World Art Post exhibition organised by us, we were very excited to be able to show them what at the time was a very new artistamp catalogue and we were happy to hear their praise.

We only managed to really see Documenta on the third day of our stay in Kassel. We ran into Géza Perneczky in the Orangerie; he invited us to Cologne for the next day… He too had diligently collected scraps of paper around Documenta, and one or two hours later he was walking past a few metres from us in Friedrichplatz searching around. We bought some more postcards in the Documenta bookshop to supplement our collection, but unfortunately we could only stand and marvel at the sight of all the books but mainly the sound poetry and experimental music records and cassettes.

We spent the last evening in Kunold Strasse with Jürgen Olbrich, who was always clowning around, and an ever-increasing company of artworks. What will be here in 100 days? – we thought. Upon our saying goodbye we were presented with a unique assemblage: a big stitched-down, screen-pressed paper bag containing all the rubbish of Documenta: pieces of unused photos, packaging materials left over from works, thrown away bills, and all manner of litter that Olbrich had collected from the artists working in the exhibition – a documentation redolent of life.