Gábor Klaniczay

Tormented body, torn clothes

The roots of performance art – two contributions from cultural history*

Performance art emerged at a time, in the sixties, when academic and avant-garde art were both trapped by museum conventions and the art market. The only way out for radical ‘art-wanters’ was to completely destroy the boundaries between art and life by declaring “Everything Is Art!” With its experiments to blend and mix everything performance art was a perfect vehicle for this ambition. Performances were put on but instead of going on the traditional stage, ‘performers’ performed in galleries and other cultural venues, even before cameras were set up in their own homes. The raw materials and techniques of the fine arts were used but instead of making artworks in the traditional sense, they created documentation. The performances were rituals but did not associate themselves with any particular religion (even though they made allusions to it). They delivered shows for the public but when performed during the intermissions of rock concerts they were perceived as unpleasant, disturbing and aggressive artistic acts; they had complete disregard even for the aesthetics of the entertaining subcultural genres (although performers gave preference to these venues over the art salons they utterly despised).

In performance art artists perform something but – as opposed to the theatre – their performance is unique, irrevocable and unrepeatable, reflecting upon the eternal questions of ‘high art’. It uses the body as its important medium – carrying the kernels of what was to become ‘body art’. The body of the performing artist(s) must endure severe things during the performance in order to perceptibly render the ‘truth’ and pathos of the work of art being created and to shock the audience into realising that what they are watching is not mere entertainment. (It is well known that this problem has been addressed many times in the area of the theatre too by Artaud, Grotowski, Stanislavski and their followers.) If blood, tears, suffering, torment, and even death were not real, the message that the performer-artist intended to howl into the world through the primary, biological energy of the tormented flesh was regarded as having no credibility.

In the history of culture Avant-garde and performance art were not the first to use the messages of the body and suffering as a complex system of symbols. In this essay I will put two early examples ‘under the scalpel’.

I.

The topic being performance art, let me first provide three famous examples from the relatively recent past.

First, let us examine the case of the Vienna Action Group. The events put on by Hermann Nitsch, Otto Mühl, Günter Brus and their friends are not referred to in art history as performances but actions, yet what these artists did at the time had a lot in common with what came to be known as performance art. The actions of Nitsch, Mühl and Brus erupted in the mid-sixties from the psychological tensions generated by the Gemütlichkeit in Vienna, and entered art history as being among the most brutally chilling, ghoulish and blasphemous performances. Everything was covered with blood, sperm, urine and excrement – the most sacred symbols of religion and humanity were dragged through the mire in the name of a new and aggressive ideal of freedom.

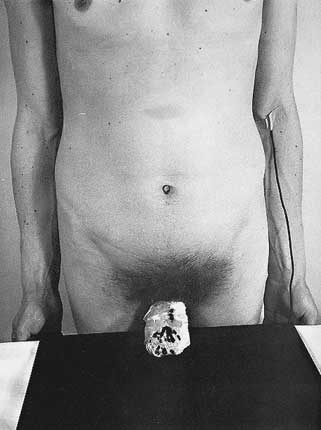

There was a heated debate in the Hungarian literary periodical titled Holmi (This and That) between László Földényi F. and Sándor Radnóti from September to November 1993 about one of the leading figures of actionism, Rudolf Schwarzkogler. Schwarzkogler committed suicide in 1969, and according to rumour he was the victim of an artistic act he inflicted upon his own body: ‘he cut off his own penis’. This was not completely ungrounded. In his 3rd action in 1965, dissected dead fish were tied with gauze bandages onto the body of a naked man, after which the penis of the model was wrapped in white gauze and laid on a black glass table top; a fish previously carved up with a razor blade, scissors and surgical instruments was tied to the penis, and they pretended to do the same to the penis. (Fig. 1)

1. Rudolf Schwarzkogler: 3rd Action, 1965

In his 5th action Schwarzkogler also came on the stage. He pasted white paint on the sex organ of Hermann Nitsch, who was wearing a long blonde wig, and carefully wrapped it in gauze (Fig. 2). That is, the penis was ‘the centre of attention’, but the story about the artist’s death resulting from self-castration which spread from 1972 proved to be a rumour. This Origenian pathos apparently did not appeal to his fellow artists, who contented themselves with grumbling about the ‘gutter press’.

2. Rudolf Schwarzkogler: 5th Aktion, 1965

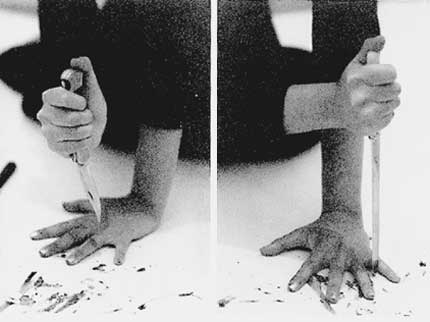

The second example is linked to an important Serbian representative of action art, Marina Abramović, who began her performance series in 1971, referring to them as rhythms, which comprised short instructions and the documentation of their execution. In Rhythm 10, for example, Marina Abramović put her left hand on a sheet of paper and kept stabbing with one knife after another between her stretched-out fingers, following a particular rhythm. When she cut her finger, she stopped and re-started the rhythm. The blood marks left on the paper were traced by her during more rhythms in which she tried to repeat the same gashes. A game that cuts into the flesh. (Fig. 3)

3. Marina Abramovic: Rhythm Nr. 10, 1974

In her action performed in 1974 (Rhythm 2) Abramović took medication in public that had an effect unknown to her, and she remained before the audience suffering through the consequences. In another action (Rhythm 0) she set out 72 objects on a table, each of which could be used on her. She wrote on her body that she regarded herself as an object, and for two hours the participants of the exhibition were able to use the objects on her body in any way they pleased without being held personally responsible.

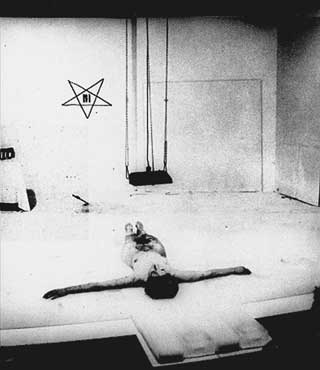

In her 1975 action, titled Lips of Thomas, Marina Abramović ate a kilo of honey and drank a litre of red wine (organic and Catholic dimension!), carved a five-pointed star onto her stomach with a razor (the red star of Communism!), whipped herself bloody (penitence and sex!) (Fig. 4), and finally lay on a cross-shaped ice block. Her body was burnt by an infrared light shining from above (the force of the elements - ordeal!) (Fig. 5).

4. Marina Abramovic: Lips of Thomas, 1975

5. Marina Abramovic: Lips of Thomas, 1975

This made her star-shaped cut to start bleeding heavily. According to accounts, the audience was able to tolerate this ‘aesthetic experience’ for thirteen minutes, and then dragged the artist off the podium of her suffering at which point the performance was over. Marina Abramović continued to exercise self-destruction in various forms in her later performances too. For example, in the 1977 performance Breathing in/breathing out she and her partner kept kissing with their noses plugged in until both of them fainted and reached a state of acute asphyxia from the used-up air they exchanged (Fig. 6).

6. Marina Abramovic - Ulay: Breathing In, Breathing Out, 1977

The third example that seems fitting here is that of Tibor Hajas (1946-1980), who represented the bloody world of body art in Hungary. Below is a detail from his writing titled Performance: Death’s Sex Appeal (The Aesthetics of Damnation) [Performance: a halál szexepilje (a kárhozat esztétikája)].

“The painter makes a gesture he was not ready for. The message arrived through his hand, his body, hence it is unrepeatable. It is clear talk. The body is the only medium that can be trusted for real. He no longer dares touch the picture. Something has come into being that he can no longer control and the rules of which he does not know. He brought to life something larger than himself and of which he can never be certain if it would turn on him. An artist must have something self-endangering. But it brings no satisfaction by itself. He received an unforeseeable gesture of redemption that did not come from him, an act of grace, something not of his choosing but having chosen him, and now he wants to perform and have performed this on himself. He forces himself into becoming an artwork; he becomes his own Golem... The performer enters his own vision. Looking back from there, every extant thing is a mere illusion, hallucination and an inferior reality. Everything is on a lower level of existence compared to what is worth living. Two underworlds, two hells staring at each other.”

Another, similar text by Hajas is titled Draft of an animation film concept [Animációs filmterv vázlata], in which he says: “There is no such thing as animation. Animation is impossible. Hence, it is forbidden... It is a sin because it offers no chance of triumph, which could be the source for new laws and new reflexes. Animation can only be achieved through deception... The theatre is a deception. Films are a deception. Animation is such a shameful deception that it is only right to treat it as a hoax.” Art cannot tolerate such deception. “I cannot deny any of my personal responsibility. No deceptive winks, no mitigating circumstances. The half-abstract panics in the brain and the pressure to decide, still in this life.”

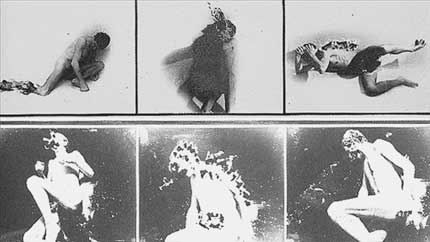

The above texts are rather shocking, especially given the threatening and profound series of Hajas’ actions performed at the time (around 1978-1980). His photos, ‘flesh paintings’ show the artist’s naked body having been defaced and ‘whipped,’ (Fig. 7) tightened by real ropes, loops, and wires, pricked by sharp needles or scorched by cadmium sparks and electricity during the increasing number of performances. (Fig. 8)

7. Tibor Hajas: Surface Torture (Fossils), 1978

8. Tibor Hajas: “Chöd” (performance), 1979

In a desperate attempt, the gestures of performance and body art endeavoured to restore the seriousness of art in a situation when it was virtually impossible. The next section is a commentary on this subject, from the perspective of the distant past. It will discuss medieval religious rites, images and descriptions in which medieval thinkers attribute religious significance to the suffering body and the torn clothes. Chronologically speaking, the second example is closest to performance art, although it will touch upon the attire of those forming part of the subculture of the period from the fifties to the seventies. Both of these examples seek to illustrate how in a milieu living by its own rules a moment comes when people display their own bodily suffering in public and assign a general message to it.

These examples from a remote era must be seen as models. After their overview, some space in this essay will be devoted to the evaluation of performance art.

II.

When discussing the medieval approach to the suffering human body, the first images that come to mind are the horrors endured in Hell and Purgatory. Eloquent accounts of these can be read in apocryphal writings dating to Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, in sermons, vision literature and texts about ‘otherworld journeys’, such as the popular stories of Tundal’s and Owein’s journeys to Hell, and of course in Dante’s Divina Commedia. Medieval theology faced an interesting and peculiar problem: if the soul of the deceased separates from his body, how can it bear the punishment to be dealt to it? Agony in those days was apparently only envisioned in physical form: through various instruments of torture, wounds, broken bones, howling; hence, the souls tormented in Purgatory and Hell were attributed a new physical existence, even inflicting various degrees of suffering depending on which body parts they sinned with.

A late medieval account of a journey to hell by two Hungarian knights, György, son of Krizsafán, and Lőrinc Tar, survived from the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries. The two men relate what they had witnessed from the sufferings in the otherworld in Ireland, in “Saint Patrick’s Purgatory”, in a pilgrim’s cave on Station Island in Lough Derg. Below is a vivid description from György, son of Krizsafán.

“In Purgatory, he saw a fiery iron wheel with countless souls hanging off it into the fire, tied by their throats and necks with snake ropes, twine, and white-hot iron chains. The wheels were incessantly turned and rotated in the fire by a lot of hideous-looking devils with great force and at speed, and the souls were constantly being bitten by a sea of fiery snakes. This is the punishment specifically imposed upon the haughty for the sin of pride.

Secondly, he saw numerous metal pans and pots on the slope of some hillocks; these were filled to the brim with fiery, smouldering, liquid gold, silver and other metals. He also saw countless souls lying on their backs, who were tied up tight with ropes of snakes and fiery chains so that they were unable to move. The devils forced the mouths of these souls wide open and kept pouring fiery, liquefied metal – gold, silver and other metals – down their throats into their stomachs; at times they hurled these souls into bubbling pots and pans. This is the punishment imparted to the greedy…

Thirdly, he saw numerous male and female souls who were dealt two horrible punishments: a collective and an individual one. The common punishment was that every soul had a solid fiery stake pierced through the middle of his or her stomach, i.e. their navels, which also penetrated their kidneys and groins. The devils held both ends of the stake and turned the wheel in the fire rapidly as you would a mill-wheel. This is the collective punishment to the lustful, for the sin of lust…

He saw many women here who, in addition to the common punishment, had their wombs pierced by a fiery iron rod and were suffering in agony. He also saw men who had bent iron instruments attached to their penises and were suffering in unutterable pain…”

And the list could go on. While theological treatises discussed in rather abstract terms how souls suffer in the other world as if they were bodies, such descriptions as the one quoted above as well as the miniature depictions and frescos (Fig. 9–10) treating these themes painted a horrid picture of the agonies sinners would have to endure in the next world. In the other world, bodily suffering represented the moment of truth, and justice followed the pattern of the worldly judicial courts, at times modifying it and not infrequently exceeding it by imposing even more severe bodily ordeals as punishment.

9. The Vision of Tnugdalus of the Hell, Visio Tnugdali, Early 14th Century

10. Punishment in Hell, Book of Hours, mid of 14. century

In the Middle Ages, the visual representation of bodily suffering served as more than just a vehicle to deter people from sinning. The connection between bodily ordeals and justice formed the basis of judicial rituals. The most archaic of these were the trials by ordeal, in which guilt or innocence was decided by the elements, but primarily by fire and water. In some cases the tried person had to fish a ring out of a cauldron filled with boiling water, in others they had to walk barefooted on nine smouldering plough-shares, in the trial by water the accused was lowered into water to see if he or she would sink or be ‘found light’ (i.e. guilty), and at times they had to hold a fiery iron rod (such ordeals by red-hot iron were carried out in Hungary at the tomb of Saint Ladislas in Nagyvárad, which is recorded in the thirteenth-century Regestrum Varadiense). In a dispute the tried and tormented bodies of the parties proved who was right by their ability to resist the ordeal or the quickness of recovery.

In the more rational society of the Late Middle Ages, the ordeals by trial, which had an uncertain ending, were replaced by the inquisitional judicial method, during which bodily suffering continued to play an important role in exploring the truth. The intense physical pain that was inflicted upon the accused – who was virtually always found guilty – was looked upon not only as a means of finding justice but also as part of the deserved punishment. This explains why the ‘first act’ in death sentences was additional torture and then public execution, which served as a ritual of deterrent, no less so than the still more extravagant continuation of purposeful torture, while dismemberment was designed to inflict the suffering of death not just once but thousands of times upon the condemned. All of this is well illustrated in Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, which begins with a detailed description of the marathon-like execution of Damiens in 1757 for his attempted assassination of King Louis XV.

Of course judicial torture did not start in the Middle Ages but much earlier. The well-known passions of the early Christian martyrs in medieval Christendom preserve the memory of Roman ‘methods’ of torture, for example. Martyrs attested to their faith with their own blood and death, and endured the most horrendous physical suffering in the hope of being welcomed in the next world. Sometimes they were roasted to death like Saint Lawrence, skinned alive like Saint Bartholomew, or thrown to lions and other wild animals (such as the famous martyrs of Lyons or Perpetua and Felicitas of Carthage), while others had their bodies broken on wheels like Saint Catharine of Alexandria, and some were beheaded, their eyes gouged out and other parts of their bodies cut off. Pious descriptions and devotional pictures demonstrate all of this with vivid naturalism.

The most horrific suffering was meted out to the female martyrs. In legends, the merciless executioners went about their work with the indifference of a butcher, cutting up the chaste bodies of female martyrs whose only sin was often no more than they were unwilling to marry the governor’s son or refused to worship Caesar’s statue. The most gruesome stories originate from the Near East. After a judge demanded that she denounce the Christian God and get married, Febronia, a Syrian woman living a chaste life, answered in a contemptuous voice that she already had a nuptial bed in heaven, where her betrothed was awaiting her. At this the judge had her flogged, bits of flesh torn out of her body, and burned with white hot iron tongs, asking intermittently if she was willing to relent. Of course the heroic, virgin martyr was unwilling to recognise the pagan gods. To this the judge had her teeth wrenched out and her breasts, hands and feet cut off in that order – and in the end, although a bloody writhing mess was all that was left of her, Febronia still refused to submit. According to the legend people began to wail and beg the martyr to relent and for the executioners to desist – but to no avail.

Beyond giving accounts of the suffering of the martyrs, passion narratives played an important role in the miracles of healing that formed part of the cult of saints. Martyrs became capable of relieving the earthly suffering of others in a supernatural way precisely because they themselves had suffered and heroically endured the torturous deaths meted out to them by evil authorities. All of this, as Peter Brown pointed out in his splendid book on the veneration of saints, is highly reminiscent of the legends pertaining to the initiation of shamans. The older shamans would pull the shamans to-be into their ceremonies to participate in various trials but also so that they could take apart their bodies and then count their bones (to establish if they had the ‘extra bone’ of the shaman), after which they put the body of the initiated back together. If anyone goes through such dismemberment and is then able to reassemble themselves, they will be capable of doing the same for others and of healing the bodies of the sick.

Of course – ultimately – the suffering of the martyrs was nothing other than the emulation of Christ. The key conceptual element of the Christian faith is the teaching that the son of God became incarnate as a human being, and in order to redeem the sins of mankind he underwent torture and crucifixion. The greatest symbol of Christian faith, therefore, became Christ’s suffering human body. This partially explains why the medieval saints and ascetics expressly sought physical suffering as a way of imitating Christ.

Pain and revulsion for the physical body as a central motif of Christianity was influenced by other late antique traditions of asceticism. The fakir-type approach, which was, so to speak, to biologically completely conquer physical feelings and desires, may have played as great a role as did Gnosticism and Manicheism, two versions of dualism which radically rejected the body. The practise of asceticism inspired by antique tradition became defining in the brutal penitential habits of the early medieval hermits (hairshirt, stone beds, etc.). However, in the Late Middle Ages all of this was supplemented by a completely different interpretation of the renunciation of the body and the endurance of suffering. From the twelfth century onwards asceticism, self-flagellation and fasting were increasingly used by adherents to experience the suffering of Christ through their own physical reality. The vir dolorum, or Man of Sorrows – the body of Christ covered in wounds – became a central element in religious thought in the Late Middle Ages. In this period, people leading a religious life often drew attention to themselves as imitators of Christ, first in the cells of monasteries and then increasingly in the public sphere through a display of flamboyant penitent acts and their own tortured bodies to demonstrate their religious devotion.

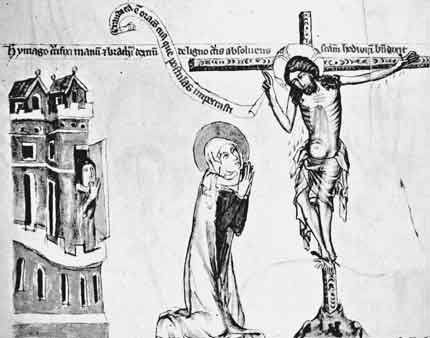

Of the many examples that can be quoted here, one is the legend of Saint Hedwig of Silesia (1174-1243) from the thirteenth century, the aunt of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, in which the following is recorded:

“So that she might live for Christ, who died for us all, the blessed Hedwig daily mortified her body with punitive lashes here on earth. Daily she accepted the cross of chastisement. With manly steps she followed Christ, unafraid of being a sacrificial lamb for the love of Him who, in his great love for all mankind, allowed himself to be crucified.” (Fig. 11)

11. The Self-Flagellation of Saint Hedwig

Many similar passages could be quoted from the lives of female saints from late medieval Italy, the Netherlands or even Eastern Europe, who, as the famous fourteenth century German nun, Elsbeth van Oye, known for her dreadful self-scourging, sought to “identify [with Christ] in the bloodiest manner possible” (die allerblutigste glicheit). Why did this happen exactly then? And why did this need to manifest in this way?

In the Early Middle Ages, God was glorified in splendid churches with magnificent liturgies and beautiful Gregorian songs in a ceremonial and ritual form that was due Almighty God. In contrast with this, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries people’s attitudes to all of this perceptibly changed. Far more attention was devoted to the Gospels and to the passion of Christ placing the story of one man’s suffering at the centre of the Christian faith. This might have given rise to the idea that perhaps Christianity could reach its moral objectives with renewed efficacy if the faithful were to again try and experience the suffering of Christ through understanding, following and, ultimately, sacrificing themselves in a Christ-like fashion to redeem others.

An interesting contradiction developed in this time. On the one hand, there was the official institutional system of the Church with its numerous religious orders, the papacy and the hierarchy of the secular clergy, the liturgy of the Church and the complex system of dogmas, all put to work to facilitate and mediate the salvation of Christian society. On the other hand, there were the lay religious movements, often declared heretical. Its members believed that the Church’s role as an intermediary was discredited since it was proclaiming the word of the poor Christ yet immensely wealthy itself. They, therefore, offered a thorny path, which could be undertaken by anyone: the ‘apostolic life’ of following Christ in poverty, to bear his cross, and together with him suffer to redeem the sinners.

The members of heretical sects that appeared on the scene in the eleventh and twelfth centuries contributed to the religious controversies what they had ‘at hand’: their bodies, their tools of physical expression. They thus attempted to demonstrate that through their own bodies they were truly practising and carrying out the teachings of the Gospels. The majority of the wandering preachers of the early twelfth century showed up in front of their public as Henry of Lausanne, a monk in southern France who left his order and around 1115 would preach in the city of Le Mans in the dead of winter, barefooted and with long, dishevelled hair. He would sleep on the thresholds of houses, and knock on doors begging for food. The adepts of the great heretical movements of the late twelfth century, the Catharsand theWaldenses, were also dressed in the torn rags of the poor and the beggars. Wearing these disturbing dress symbols, they burst onto the scene of religious disputes and were easily able to win over the faithful from the priests who opposed them from the backs of their horses dressed in expensive clothes and episcopal vestments.

It was precisely as a result of this recognition that the mendicant orders, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, formed at the beginning of the thirteenth century, learning from the preceding one hundred years of disputes with the heretics. Saint Francis came from a wealthy family of merchants in Assisi in central Italy. After an idyllic period as a child and young man Francis turned to religious life upon suffering captivity and sickness, which was then followed by visions. In the main square of Assisi he tore off his fine clothes, gave them to his shocked father, then stark naked he donned the rags of a beggar. This change of dress demonstrated the kind of religious life he had embarked upon. Hopefully, it may not come across as too profane if I point out that these parable-like, thought-provoking scenes were at the same time highly theatrical and in many ways bring to mind the genre of modern performance art, and in a certain sense were its forerunners. The deeds performed by Francis contain shocking and spectacular scenes in the hundreds: how he preached to the birds (Fig. 12), how he sent out Brother Rufino to preach naked and how he tamed the wolf of Gubbio – all of these can be read in his ample collection of Latin legends, and the bunch of anecdotes rendered in the Italian vernacular, titled Fioretti (Little Flowers of Saint Francis).

12. Giotto: Saint Francis Sermon to the birds

The stories often relate how Saint Francis endured extreme forms of physical trials for the sake of showing solidarity with sufferers. One such, for example, was when he ate from the same bowl as a leper, whose “body was covered in scabs and pus, and mainly his fingers with which he was eating, were stumpy and bloody, and every time he reached into the bowl the blood flowed from them.” By sharing the bowl Saint Francis demonstrated that even until his last breath he was willing to take communion with the most outcast of society, lepers, who medieval society kept completely segregated.

In the context of medieval practices forming the roots of performance art, it is important to mention that Saint Francis of Assisi is also held to be the originator of late medieval religious theatre. When in 1223, in Greccio, some fifteen days before Christmas, he had a crib erected because – as he said – “I want to conjure up the memory of the infant of Bethlehem, and with my own eyes behold the limitations and discomforts of the child; I want to see how he was placed in the crib and how the horse and the donkey lay on the straw.” It is at this point that a change in religious concepts is manifest: attention increasingly expanded to the material reality of the tiniest details, and spirituality became closely embedded in objects and bodies.

The most alarming miracle performed by Saint Francis took place in the bodily realm: two years before his death, the stigmata of Christ appeared on his suffering, tortured, sick body on the mountain of La Verna.

“He saw in the vision of God a man, having six wings like a Seraph, standing over him, arms extended and feet joined, affixed to a cross. ... he greatly rejoiced, and was much delighted by the kind and gracious look … but the fact that the Seraph was fixed to the cross and the bitter suffering of that passion thoroughly frightened him … [meanwhile] … Signs of the nails began to appear on his hands and feet, just as he had seen them a little while earlier on the crucified man hovering over him. His hands and feet seemed to be pierced through the middle by nails, with the heads of the nails appearing on the inner part of his hands and on the upper part of his feet, and their points protruding on opposite sides… His right side was marked with an oblong scar, as if pierced with a lance, and this often dripped blood, so that his tunic and undergarments were frequently stained with his holy blood.”

The wounds were discovered only after his death (although, allegedly, one or two initiated brothers knew about them). The legend of his stigmatisation encapsulated all that the fellow members of his order thought of him in a spectacular bodily metaphor. They referred to him as Alter Christus, i.e. one who experienced the sufferings of Christ so that they would also cause changes upon the body. The Franciscans needed this story, disseminated by Elijah of Cortona, because – it seems – even the most fitting metaphor was not convincing enough in the Middle Ages if it was not confirmed by visible bodily marks (Fig. 13).

13. Cimabue: Saint Francis

The example of Saint Francis may not only have exerted so great an effect because he was supported by the papacy and one of the most influential orders of the Late Middle Ages. Another major factor that contributed to his influence was that he actually embodied a model of behaviour and mores that had been forming for one and a half centuries, which had become triumphant and was made accessible to huge crowds through his example. In the diverse urban culture of thirteenth-century Italy, we can clearly observe the popularity of the two directions marked out by Saint Francis: the theatrical, or what could be deemed performance-like religious manifestations, and the profound, emotional identification with Christ’s suffering.

As far as the theatrical religiosity is concerned, the example of the Italian Alleluia of 1233 is edifying. This mass peace movement was led by Dominican and Franciscan friars. One of the initiators, Giovanni da Vicenza, would parade through various little towns dressed as John the Baptist in a hair shirt and barefooted, carrying an enormous trumpet and accompanied by large groups of children. He would declare that from then on there would be peace, blessed be the Father, and at this point he would blow the trumpet while the children sang in chorus: Alleluia…and the Son…Alleluia, and the Holy Ghost – Alleluia… And it was from this that the movement derived its name, and soon spread to dozens of towns with wave after wave of new preachers, each of them adding some kind of novel attribute and idea. The squares and streets were full of such people who moulded their questions about religion in a theatrical form, and condemned the Church to a secondary role.

The centuries of the Later Middle Ages resounded to the clamour of similar mass movements. The most flamboyant were the Flagellants,who in 1260 set out from Perugiain their procession of penitence, which was later revived during the period of the Great Plague in the fourteenth century, between 1348 and 1350, as one of the tools of expiation and self-reproach after the calamity (Fig. 14).

14. Flagellants, Illustrated Chronicle (Chronicon Pictum)

The success of the Flagellants lay in their ability to combine theatrical performance techniques with an open display of bloody suffering. Their spectacular processions of penitence were elaborately choreographed to symbolically match the 33 days of Christ’s years on earth; moreover, they were open for anyone to join. Similar to this was the network of processions all over North Italy in 1396 by the Bianchi, who flogged themselves while dressed in white cowls.

Innovative theatrical religiosity found its own official feast day towards the end of the thirteenth century: the Corpus Christi feast, the celebration of the Real Presence of the body of Christ in the Eucharist, was introduced in 1264. In many places the urban processions were accompanied by mystery plays which each guild created and performed on moving carts, using amateur actors from the respective professions, at times with an inventiveness and ‘modernity’ impressive even to the modern eye. For example, in the fourteenth century English ‘pageant’from the Wakefield cycle the crucifixion scene was presented, in quite a profane manner, by the nail-making smiths from the perspective of their own craft. Additional steps towards religious theatre were the sermons based on the tableaux vivants, which were chiefly applied by the Franciscans. The scenes took place as the sermon was given by the preachers who in the appropriate moment would pull the veil off the actors who would then enact a particular scene, such as Christ being flogged.

However, not everything took place in the public eye. It is only from the accounts given by nuns, the confessors or ‘spiritual guides’ that we know how women living a secluded, religious life locked in cells followed the example of Saint Francis.

It is pertinent at this point to cite four stories on the development of the female religious ideal in the Later Middle Ages, which not only serve as illustrations but also highlight the ambitions of the ones concerned to outdo each other in regard to using the most original and extreme methods.

Angela of Foligno (1248-1309) was a great mystical saint of the late thirteenth century who after certain tribulations – being widowed and suffering the death of her children – began, in her later years, to see visions in the Church of the Convent of Saint Francis in Assisi. Her visions provided a popular form for the imagination of a new religiosity adopted by laywomen, and were recorded by several scribes, one of which was her relative, the Franciscan friar Arnaldo. Angela’s visions were expressed in metaphors with enchanting sensuality her unquenchable love for her Heavenly Bridegroom, whom she had loved as an infant and then as a man, and mourned as a tortured victim. It is interesting that although her stories were imbued with a warm tone and exuded an Umbrian cheerfulness, akin to the spirituality of Saint Francis of Assisi, they were also suffused by the morbid tone of death and suffering. In one of her most famous visions she found herself, on Holy Saturday, in Christ’s tomb, hugging the dead Saviour’s body, kissing the wound in his side and his mouth, while feeling inebriated with the sweet scent that emanated from him. A surprising correspondence with the symbolism of this vision came ten years later, when, in a moment of depression and faltering self-confidence, she planned to deny the veracity of her own visions by parading naked through the town of Foligno with dead fish and rotting meat hanging from her neck to loudly proclaim: “I lied to you, I am a worthless, wicked and vain woman, and the rotten embodiment of all manner of sin and purification.” Her faithful followers prevented her from carrying any of this out, but it is duly stomach-churning to envision the physical metaphor in which her plan was to take shape. This episode demonstrates the kind of passions, emotions and energy mobilised when quite literally “the Word became incarnate” in the Later Middle Ages.

Lukardis of Oberweimar (1262-1307) was a contemporary of Angela. She lived in a monastery and was paralysed, or almost paralysed. She was afflicted by the most terrible physical suffering and condemned to immobility. However, her ill fortune took a turn when the Holy Virgin appeared to her, and fed her with fried chicken as well as enlivening drink, her own motherly milk. After this the suffering Christ himself appeared in her visions, with his body steeped in blood. Christ then told Lukardis, who had fallen to the base of the cross, to stand up and help him. “How can I help you Lord?” she asked, and when she raised up her eyes, she saw that Christ’s right hand had come loose from the cross and that this was clearly causing Him terrible pain. “Help my hand,” Christ implored. Lukardis was unable to do this at first. “Attach your own hand to mine,” said Christ, “and your foot to my foot, your chest to my chest. And if you hold your body tightly to mine, you can relieve my suffering.” It was at this moment that Lukardis understood: she had to take Christ’s sufferings upon herself, and this made sense of her own suffering. All of this was at first only the stuff of visions, but two years later the holy wounds really appeared on Lukardis’ body, and then began to bleed. This usually happened on Fridays, but more especially on Holy Friday, which everybody of course took to be a miracle. A similar vision of the moving crucifix also occurs in the contemporary legend of Saint Hedwig of Silesia (Fig. 15).

15. The moving crucifix is blessing St. Hedwig

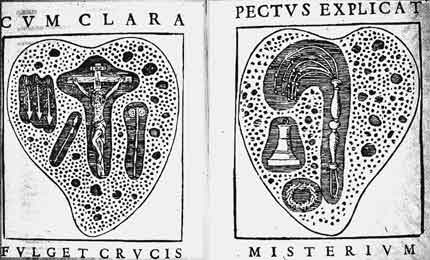

Clare of Montefalco (1268-1308) had a vision in which Christ stabbed her in the heart with a crucifix and planted in her the instruments of His suffering (Fig. 16). News of this of course soon spread. Out of curiosity, or more out of a desperate desire for miracles, after Clare’s death her fellow nuns immediately extricated her heart, and there within it – lo and behold – were the instruments of Christ’s suffering: the crown of thorns, the scourge, the vinegar-soaked sponge, the spear, the crucifix and the nails (Fig. 17).

16. Christ implanting his Cross in the heart of Saint Clare of Montefalco

17. Clare of Montefalco’s Heart

This is all linked to the cult of Arma Christi, which emerged in the early fourteenth century, with the Italian Dominican, Venturino de Bergamo, being its passionate proponent. Looking back from the perspective of modern art, devotion having been transferred to the instruments of suffering (which again usually took the form of bodily suffering and bloody flagellation) brings to mind a saying by Joseph Beuys: “When you cut your finger, bandage the knife.”

The most well-known female mystic of the Later Middle Ages was Saint Catherine of Siena (1348-1380). It was through her that late medieval religious spirituality, built upon the destruction of the body, manifested in the most extreme fashion. As a girl she ignored the pleas of her parents to desist from the awful blows she inflicted upon herself along with extreme penances, as she was not to be deterred from the path of suffering she had willingly embraced, which were soon enhanced by additional tortures inflicted upon her by the devils she saw in her visions as well as by Christ-like agonies: she was given a crown of thorns, and Christ drove a nail through one of her hands. One day when she was filled with aversion at having to dress an old woman’s wounds and thus beset by pangs of guilt, she suppressed her disgust, and sucked the liquid pus from the wounds, the taste of which she described as heavenly. In a vision following this Christ rewarded her by allowing her to drink from the wound in His side; and since she was able to conquer her human nature Christ bestowed upon her His very life-blood, seen as the elixir of life in medieval Christianity. Finally, as the crowning glory of all this suffering, Catherine of Siena also received the stigmata of Christ in 1375, in Pisa, while falling into ecstasy before his picture (Fig. 18). It was thanks to her popularity that the Dominican order was able to catch up in this field with their chief rivals, the Franciscans.

18. The Stigmatization of Saint Catherina of Siena

These few examples already illustrate the contradictions that characterised the changes in religious concepts in the Later Middle Ages. In response to the problems of society, suffering, sickness and exclusion, the religious movements revived the message of the New Testament propagating self-assumed, voluntary poverty and the renunciation of worldly things. They tried to make religious penitence a collective experience through concrete acts – the rending of clothes, inflicting bodily torment, practicing repentance and atonement, as well as organising public self-flagellation processions – and thus managed to bring the teachings of the Gospels close to people and invested in them a social content. During this process physical suffering was an end in itself, lacking any altruism: it was a means of identifying with the Word Incarnate, and the redeeming sufferings of Christ. However, none of this could abrogate the earlier concept of aversion felt at the sight of the body, which, like a memento mori, a dance macabre, bore the warning signs of the agonies of Hell to come.

III

In order to take a closer look at the more recent roots of performance art, we should take a huge leap in time to the twentieth century and examine the dress styles, values, and the approach to the body in the different subcultures of the period. Let me disregard for now the imperfect nature of the conceptual tools we have available for the analysis of the different levels of culture, such as ‘subculture’ (meaning culture underneath what we regard truly ‘culture’), and ‘counterculture’, a category emerging from the ‘rainbow palette’ of the political ideologies in the sixties.

The emergence of subcultures was one of the typical features of nineteenth and twentieth century urban reality. These were the cultures of social layers and groups that were unable or unwilling to conform to the modern, uniform, mass civilisation that had evolved in cities, and thus created in the ‘urban jungle’, the ganglands and hidden corners out of reach for the disciplinary authorities, their own way of communication and cultural manifestations reminiscent of the ‘communal’ life form and the ‘primitive’ wilderness of old civilisations. The culture of workers, sailors, immigrants, tramps, beggars, criminals, racial and ethnic minorities and young people in gangs had a wide range of manifestations, including communal rites, slang, argot, folk genres (jokes, stories, songs, legends) and musical versions of the performing arts, all of which were discovered and exploited by the commercialised culture in cities where people were longing for a kind of urban romanticism. And to return to my original train of thought, one of the most characteristic media or manifestations of these subcultures was the body – a carrier of gestures, hairdos, scars, tattoos, and idiosyncratic or even alarming clothes.

A noteworthy symbolic overlap is that one of the very first music- and lifestyles that grew out of subcultures, namely ragtime, which had its heyday at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, borrowed its name from the word ’rags’, similarly to one of the earliest medieval heretic movements, called the pataria, which thrived in eleventh-century Milan. The body retained its importance as a medium of expression in the ‘nude fashions’ of the roaring twenties, the swing pants of the thirties, and the famous ‘zoot suits’ in the forties worn by the cultural rebels in California. In this period sociologists identified a new attitude held by working class youths to their work garments: the denim trousers, or blue jeans, leather jackets and T-shirts. While in their leisure time older people took off the work garments and strove to don a more ‘civilian’ look, Marlon Brando type youths wore these clothes in a most provocative fashion, in public – as one could see in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront. They wore with defiance what was seen as their stigma in the eyes of others (Fig. 19).

19. Marlon Brando, 1953

In the early fifties, Normal Mailer discovered a peculiar cultural paradox in regard to subcultures. The up and striving working class youth and the marginalised members of society appeared in the ‘guise’ of the gangster dandy, called the hipster, showing off the traditional dress symbols of this particular subculture in a provocatively gaudy and slick manner. A similar cast were the Teddy Boys, the young ‘ruffians’ parading themselves in suburban pubs dressed in turn-of-the-century Edwardian suits, and tempering their outwardly gentlemanly appearance by razor fights. Paradoxically enough, on the scenes of the urban underworld, it was the intellectuals that represented the more ragged, Marlon Brando type of style. The followers of Allan Ginsberg and William Burroughs, called beatniks, virtually turned their backs on modern civilisation in an attempt to survive the increasingly mono-dimensional reality of the fifties. They acted as cultural guerrillas, tramping along with dirty feet, in torn jeans, drugged, waking up in their own vomit.

The riot of the Beat Generation assumed a mass scale. The “angry young men” appeared in film and literature, smashed the equipment at concerts, and their howling rock music became box office hits (Fig. 20). The new philosophy of the young generation was symbolised by the flannel shirt with rolled-up sleeves and worn-out, torn jeans, in stark contrast to the well-kempt adult society in white-collars and suits.

20. Concert of Bill Haley, 1954

Besides being manifest in the attitudes of the masses of young people, subcultures lived on and retained their unique character. The clashes between the mods and rockers in Bristol 1962, for example, created a remarkable media fury. On one side of the conflict were the rockers, harking back to the fifties, wearing leather jackets and riding Harley Davidsons to show off their masculinity, and kitted out with chains and brass knuckles symbolising brutality; on the other side were the stylish mods, clad in tailored suits and riding scooters, both following the fashion of the day and taking a cynical approach to it. The former had their hair greased and curled, the latter wore it combed to the front. While the rockers adopted the beatniks’ criticism of civilisation, the mods were modernists, and – as Tom Wolfe also points out – they established an urban underground culture that pointed towards Pop Art. Yet, this did not even remotely mean an acceptance of ‘middle-class’ norms; it is enough to think of the aggressive and erotic characters in Clockwork Orange with their artily slashed garb.

The hippy style, which erupted onto the scene in 1967, was also a strange mix. The well-off children of the middle class embraced and optimistically praised naturalness and carnality (Fig. 21). They rejected civilisation, threw away their wrist watches, and only sat in a car when they hitched a ride. They replaced their well-kempt hairdos with dishevelled hair, and opted for the cult of body odour instead of cleanliness. “I love the smell of my armpits,” said Jerry Rubin, although the smell of tramps probably offended even him. Hippies put behind shyness and propagated nudity with an almost ideological rigour, declaring a sexual revolution. “Join the holy orgy, Kama Sutra, everyone.” Yet, this freedom was slightly forced. A psychologist would probably have an idea or two about the deep seated triggers behind the hippy attire of torn jeans already in the sixties.

21. Hippie couple – Isle of Wight, 1970

By the seventies the optimistic body cult of the hippies gave way to a far more tormented body culture. The ‘new nasties’ re-appeared on the scene. One such group were the skinheads. They cut their hair short, had a grim look and wore their clothes – checked flannel shirts, high boots and garters – once again as a stigma. There was nothing aesthetic in their appearance, and they emanated fascist aggression going against the optimistic worldview of the hippies in ways well known from cultural history. In the early seventies, rockers came out of the woodwork with scarred faces and wearing their peculiar armours: leather suits with cuts all over, adorned with chains and wires in a haphazard fashion. Speed and fights were not infrequent occurrences; it is enough to remember the Rolling Stones concert in Altamont, for example, when Hells Angels, acting as brutal stage-guards, beat up and killed a black youth, thus giving a deadly blow to the Woodstock-utopia.

When some artists left behind their studios announcing the principle of everything is art, at a revolutionary time with student riots and other manifestations, the art scene was bound to provide its own response to the series of youth subcultures.

Andy Warhol was a leading artist personality of the sixties and seventies. In his version of Pop Art he did not reject modern consumerism like the beatniks and youth subcultures did but instead tried to show what was aesthetic and entertaining about its artificiality and uniformity. He took on consumerism with an ostentatious, cynical and absent-minded smile and started to play around: first with Coca Cola advertisements and cans of Heinz Baked Beans, and then with actors and singers elevated into stars, and eventually with life itself. His films featured not just stars but ‘superstars’ – Baby Jane Holzer, Edie Sedgwick, Viva, Susan Bottomley, Ondine, Gerard Malanga, Joe Dalessandro – who he selected from among the demi monde divas and amorosos of subcultures. His aim was to prove that anyone can become a star, moreover – as a double twist – to show that it is actually the dilettantism of superstars that enables them to transform into real art what the ‘commercial stars’ – Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe – were only able to do in the ephemeral world of mass culture.

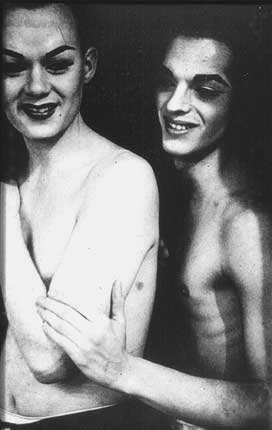

Warhol’s messages pertained not only to stars but also to the body. In his films titled Kiss, Blow Job, Flesh, Trash, Chelsea Girls, My Hustler made between 1963 and 1966, he presented nudity and sexual acts in a shocking matter-of-fact detail, challenging all kinds of taboos. Even though this apparently harmonised with the then topical slogans of the sexual revolution and liberation, it advocated its exact opposite. As Warhol saw it, the ongoing ‘revolution’ was a mere vanity fair, laden with mannerisms and a desperate striving to look free, when in fact it had none of the genuinely liberating and cathartic sensation of freedom. It takes a lot of learning and effort for a man just to be masculine and a woman to be feminine, and there were many who failed in this simple task. According to Warhol, in the laborious role-play referred to as sexuality real success was achieved by those who tried to cross from one sex to the other; for example, by the transvestites, the men who turned themselves into women. The transvestites who gathered around Coney Island were first spotted by the photographer Diane Arbus (Fig. 22), but it was Andy Warhol who made them into cultural icons (for example, Candy Darling and Jacky Curtis). Transvestites conveyed a peculiar artistic message about the human body: while it challenged one of the oldest sexual classifications, the male and female were mixed in their androgynous bodies in an aesthetic way.

22. Diane Arbus: Transvestites at Coney Island, 1962

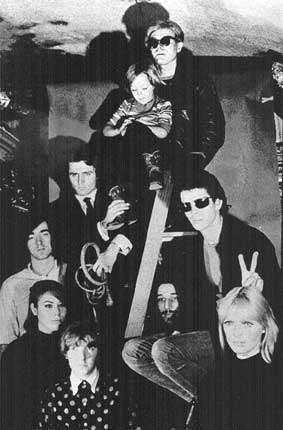

The theme of transvestism took Andy Warhol’s art to a new level, since after including the personalities of the subculture of the day that could be ‘starred’ and exhibited, he made entire milieus and lifestyles into the theme of art. As part of this process, he turned his attention to rock music. Velvet Underground (Fig. 23) was formed in New York in 1966 with Lou Reed and John Cale as its leading members.

23. The Velvet Underground, 1968

(At the top of the ladder: Andy Warhol, down on the right Lou Reed and Nico)

Instead of doing what Bob Dylan and bands that followed in the footsteps of the Beatles did – who showered their fans with love and, thinking of themselves as rebels, took their audience on a journey to a beautiful Woodstock utopia – they wore black glasses, literally played with their backs to the audience, acted out sado-masochistic scenes, and sang about fetishes, shiny boots of leather and whips (Venus in Furs). Instead of the hippies’ rainbow-coloured dream world induced by weed and LSD, they glorified heroin, which lured its users to death. They played the concert that stirred the greatest scandal at the annual dinner of the New York Society of Clinical Psychiatry held in the Delmonico Hotel (where, due to the snobbery and imprudence of the coordinators, Andy Warhol was asked to organise an art performance). The next day’s headlines broke news about a “shock treatment for psychiatrists”: while Velvet Underground was performing its ‘whip dance’ accompanied by deafening screeching, the superstars of Andy Warhol’s studio, called Factory, were running up to the participants bombarding the psychiatrists and their spouses dressed in tuxedos and ball gowns with provocative questions like: “What does her vagina feel like?”, “Do you eat her out?” “Is his penis big enough?”, “Why are you getting embarrassed? You’re a psychiatrist; you are not supposed to get embarrassed!”

Andy Warhol and his associates directed people’s attention to the tensions between the love and hatred felt for the human body. On one end of the spectrum was the milieu of ‘counterculture’ which cultivated the natural state of the body – long hair, Paradise-like nudity, and free love – the utopia we can see in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point. The other end of the spectrum was occupied by the ‘new wave’, which either ironically or playfully embraced pretence and role-playing, being fully aware that it was all forced, moreover coupled with suffering and stigmatisation, but could not care less.

Warhol’s ideas about the body were most closely expressed by David Bowie’s career in the early seventies. Bowie started out as a hippy and based his approach on the hippy attitude to clothes where the outer bodily symbols reflected the inner moral and cultural choices, and highlighted one’s personality. However, Bowie turned this principle inside out and made it into the starting point of the opposite message: outer appearance – the role – appropriated the body and the personality. In other words, Bowie became the incarnation of the characters he himself invented (Ziggy Stardust, Alladin Sane, Thin White Duke). His hair dyed flame-red, androgynous transvestite costumes, on-stage imitations of sex acts by far exceeded the usual stage roles of the performing arts (Fig. 24). They sealed their ironic choice of a role by altering their bodies in a deadly serious fashion (“Shaved her legs and then he was a she…,” to refer back to Lou Reed), yet, after some time, they provocatively replaced these shockingly transformed bodies again and again.

24. David Bowie concert

The stars of counterculture, burdened by ever intensifying tensions, would often try to inflict damage on their own bodies to add more gravity to their howling. This was still done with unleashed carelessness by the first group of the ‘martyrs’ of rock, namely Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison. But then, the proponents of the more aggressive musical styles of the mid-seventies made self-damage part of their expression: Patti Smith, for example, jumped off a platform once and almost broke her spine; Iggy Pop smashed into a loudspeaker and was almost electrocuted. The same tendency reached full swing in the punk movement, which came onto the scene in 1976–1977.

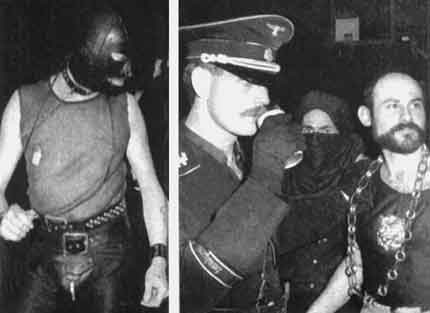

The punk ‘dress code’ demonstratively spat in the face of the lifestyle of both the white collars and the flower children, equally seen as middle class. Going against the exotic, Indian beauty of counterculture, punks pulled drab bin bags on their heads, and instead of pearls, they ‘decorated’ their clothes with toilet chains and plugs, and paraded themselves in torn bras, unzippable leather helmets and handcuffs purchased in sex shops. They proclaimed hatred instead of love, drew swastikas on themselves and wore Nazi armbands. Instead of preaching about emancipation and the sexual revolution, young men would lead their girlfriends, showing provocatively animalistic features, on a lead. It was a zombie aesthetic, a morbid indulgence in using shocking signs, and, again, things cutting into the body, the flesh. The green-lilac zig-zag and the Mohawk hairstyles were indelible signs of the punk identity. Safety pins, rings and chains pierced into earlobes, nostrils, lips and tongues were a new form of tattoo, and enhanced the aesthetic of the shockingly gaudily tormented, deformed and torn-apart clothes. Further emphasis was lent to all this by stars and music bands with speaking names: the Sex Pistols (two of its members being Johnny Rotten, and the soon-to-be rock martyr Sid Vicious), Clash, Stranglers, Siouxsie Sioux and the Banshees. Photographers found a fitting name for the book that introduced this hellish cavalcade: In the Gutter, and it did not take long before fashion designers started copying punk dress ideas (Fig. 25-26), (Fig. 27).

26. Punks, 1977

27. Clients of a sado-maso bar 1977

The culture of clothing reached such an extreme dimension that the members of the subcultural scene all became participants in a gigantic performance, a collective work of art. Indeed, the punks realised Andy Warhol’s initiative by elevating the clothing styles and attitudes of a subculture into the world of art. This was also spotted by the artists of the seventies, such as by David Byrne, who formed Talking Heads, Brian Eno, who mixed experimental and new wave music, and Gergely Molnár and László Najmányi in Hungary. Thanks to the paradoxical messages conveyed by the medium of the body, the symbolism of rock music and the avant-garde got into a close symbiosis in the mid-seventies.

IV

So has the overview of the medieval mystics and then that of the subculture fashions got us closer to understanding performance art?

What needs to be emphasised when drawing a parallel with the Middle Ages and performance art is that the sight of the body and body pain as well as the penitential techniques linked to these had been placed at the centre of religious practices. The boundary that had separated the official church from layman’s practices became penetrable. In the early thirteenth century, the church, which had previously tried to ban laymen from active participation in religious practices and force them into a passive role, realised that in order to be creditable in spreading the Gospel they had to include the laymen. Hence, by allowing Saint Francis of Assisi to preach, a new, in-between genre came into being, laying the foundation for a new tradition in the late Middle Ages: that of religious performance, or religious theatre.

If, somewhat stretching the parallel, the above is applied to modern art, it can be seen that a similar transformation took place in the history of the latter. Elitist art, museums and galleries had their own priests, temples, popes, as well as their own liturgies and conventions. Likewise, they had their own saints and doctors, and a complicated intermediary system that built a virtually impenetrable wall between laymen and artists. And of course there were the heretics of modern art: starting at the beginning of the twentieth century, the old system was challenged again and again by the Avant-garde. Then, sometime in the sixties the Avant-garde rebellion extended beyond the narrow world of artists and reached the masses. A vital role in this breakthrough can be attributed to the fact that the esoteric manifestations of modern art increasingly used the popular medium of the body and clothing to convey their message. The slogan that “everything is art – everybody is an artist”, as well as the diversity of ‘in-between’ genres of the sixties and seventies rejuvenated the world of art to the same extent as the host of religious movements of the late Middle Ages had revitalised Christianity.

The other contributing factor to this transformation can be found in the milieu of subcultures and youth fashions, the other theme of this writing. The inclusion of subcultures in art brought an elemental boost for artists that were disposed in this direction and introduced them to a wide audience. Then this exerted an influence on the subcultures themselves. Real artists were working on enriching the range of subculture styles. Their systems evolved into a cultural philosophy and the conflicts, alternations and revivals of the various styles provided a broad context for artistic manifestations, including performance art. But the greatest significance of the role of clothing and the attitude to the body in subcultures was that they disseminated the ironic-aesthetic approach to culture and lifestyle to a wider segment of society. They widely propagated the importance of masks, symbolic acts and the ‘decoding’ of symbols, thus acquainting people with a kind of sensitivity that was suitable to form the basis of a more popular form of modern art frequently accompanied by rock music.

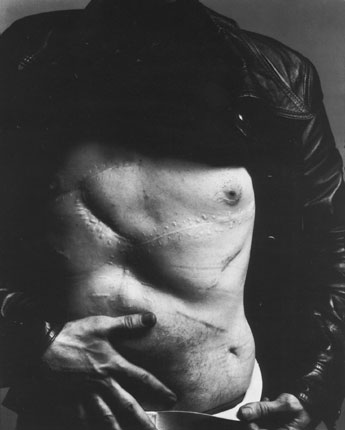

This train of thought can be fittingly illustrated by a photograph that Richard Avedon took of Andy Warhol in 1969, after the artist had survived the bullets shot at him by Valerie Solanis, a feminist superstar in his circle. This photo, titled Andy Warhol. Artist (Fig. 28), shows the artist with stitches in his body and standing as a personification of vir dolorum in a dangerous, modern world. This image also confirms that despite all its cynicism, perversion, recklessness and frivolousness, Andy Warhol’s Avant-garde managed to realise a fundamental truth: an artist, when in the thick of things, will have scars on his body.

28. Richard Avedon: Andy Warhol

The essence of performance art is, in part, the same.

Bibliography:

This text is a revised version of the lecture delivered on 3 May 1995 in the series titled Performance organised by the Artpool Art Research Center, and first published in print in Szőke, Annamária (ed.): A performance-művészet [Performance Art], Artpool – Balassi Kiadó – Tartóshullám, Budapest, 2000. The bibliography is not complete, and only includes the sources of quotations as well as references supporting the main arguments, and starting points for further research.

I. Debate on performance art: László Földényi F.: „Az érzékek purgatóriuma. Rudolf Schwarzkogler (1940-1969)” [Purgatory of the Senses. Rudolf Schwarzkogler (1940-1969)], Holmi, 1993/9 1322-1326.; Radnóti Sándor: „Levágta-e saját farkát Rudolf Schwarzkogler? (Vitairat)” [Did Rudolf Schwarzkogler cut off his penis? (A debate)], Holmi, 1993/10 1482-1488.; László Földényi F.: „A testet felszabadító bécsi akcionizmus (Válasz Radnóti Sándornak)” [Vienna Actionism Liberating the Body (Reply to Sándor Radnóti)], Holmi, 1993/11 1626-1634.; documentation of Marina Abramović’s actions: Marina Abramović, ed. Friedrich Meschede, Edition Gantz, 1993; the Tibor Hajas quotes are taken from the edition in memoriam Hajas published by the Magyar Műhely - d'atelier in 1985, edited by László Beke and György Széphelyi F. (see the bibliography of works on him in that edition).

II. On the concepts of the body in the Middle Ages in general, see the studies and detailed bibliographies in Peter Brown: The Body and Society. Men, Women and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity, New York: Columbia University Press, 1988; and Michel Feher et als. (eds): Zone 3: Fragments for a History of the Human Body, New York: Zone Books, 1989. On how Hell was envisioned in the Middle Ages, see Jérome Baschet: Les justices de l'au-delà. Les représentations de l'Enfer en France et en Italie (XIIe-XVe siècle) Rome: École française de Rome, 1993; Caroline Walker Bynum: Fragmentation and Redemption. Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Zone Books, 1991; ead. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995. The quoted passage from György, Son of Krizsafán’s journey to Hell: Tar Lőrinc pokoljárása. Középkori magyar víziók [Lőrinc Tar’s Journey to Hell. Medieval Hungarian Visions]. Ed. Sándor V. Kovács, Budapest: Szépirodalmi, 1985. 107-108; on Christian martyrs, see Vértanúakták és szenvedéstörténetek, Ókeresztény Irók [Acts and Passions of the Martyrs. Early Christian Writers] 7 Budapest: Szent István Társulat, 1984; for the quoted story of Febronia, see Sebastian Brock, Susan Ashbrook Harvey (eds): Holy Women of the Syriac Orient. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987; for the comparison with shamanism, see: Peter Brown: The Cult of the Saints. Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981; for trials by ordeal, see Talal Asad: “Notes on body pain and truth in medieval Christian ritual”, Economy and Society 12 (1983), 187-327; Robert Bartlett: Trial by Fire and Water. The Medieval Judicial Ordeal. Oxford: Clarendon, 1986; on the medieval concept of suffering in general, see Esther Cohen: “Towards a History of European Physical Sensibility: Pain in the Later Middle Ages”, Science in Context 8,1 (1995), 47-74; Piroska Zombory-Nagy, Véronique Frandon: „Pour une histoire de la souffrance: expressions, représentations, usages”, Médiévales 24 (1994), 5-14; I wrote a detailed documentation about the female saints in the Middle Ages: Tibor Klaniczay and Gábor Klaniczay: Szent Margit legendái és stigmái [The Legend and Stigmata of Saint Margaret]. Irodalomtörténeti Füzetek, 135. Budapest: Argumentum, 1994; the quotation on Saint Hedwig can be found in that volume, 161; the quoted legend on Saint Francis – Thomas of Celano:“The Life of Saint Francis”, in Regis J. Armstrong, J A. Wayne Hellmann and William J. Short (eds), Francis of Assisi: Early Documents. Vol. I. The Saint. New York: New City Press, 1999, 180-310; about stigmatisation, see Chiara Frugoni: Francesco e l'invenzione delle stimmate. Una storia per parole e immagini fino a Bonaventura e Giotto. Torino: Einaudi, 1993; about the body of Christ: Miri Rubin: Corpus Christi. The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991; Leo Steinberg: The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. New York: Pantheon, 1983; on Saint Catherine see Raymond of Capua: The Life of St. Catherine of Siena. transl. George Lamb, Harvill Press 1960.

III. For an orientation on subcultures: Dick Hebdige: Subculture. The Meaning of Style. London-New York: Methuen, 1979; Stanley Cohen: Folk Devils and Moral Panics. London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1972; Jerry Rubin: Do It! Scenarios of the Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970; Andy Warhol & Pat Hackett: Popism. The Warhol '60s. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980; Jean Stein: Edie. An American Biography. London: Panther, 1984.

* Published in Hungarian in Klaniczay, Gábor: Ellenkultúra a hetvenes–nyolcvanas években [Counter culture in the 1970s-80s], Noran, 2003, 2004. English translation: Krisztina Sarkady-Hart, 2017