Who has not lain in the grass, perchance biting on a blade of grass, and keenly watched the clouds, only to become captivated by their perpetual and inexplicable movements? Who is not familiar with the childlike, naïve amazement and tremor awakened by the infinity of nature? How can an artist transform this peaceful, meditative contemplation into an artistic manifesto, and applying an obstinate consistency, turn it into a kind of individual mythology? Lengyel links geometry and myth, making the relationship between clouds and the triangle (a rational shape which at the same time is determined by the laws of nature) virtually the sole element of his art.

“It is my fixed idea that there are moments when the constellation of the clouds fills the visible dome of the sky so that holding my canvasses up the depictions continue outside their boundaries, blending into the spectacle of the moment. I do not use models for these pictures; they are conceived by my experiences of staring and wondering.

Why do I paint clouds? Because they are the manifestation of the changing nature of material. This is not ethereal but heavenly. These paintings are the continuation of a childhood dream: like Leonardo, seeing figures in amorphous patches...”

András Lengyel’s unrelenting interest in the cloud motif makes him the most active member of the Cloud Museum. The first time this motif appeared was in 1975 in his series entitled Marmara Sea from the Window of Rákóczi’s House in Tekirdag, and then on two slides the artist made on the two shores of the Bosporus, on the boundary between Europe and Asia.

It was on the Road Signs series (1978) that clouds and the triangle first appeared together, marking the beginning of their organic unity: the signs warning of danger first including a number of "dangerous" elements of nature (birds, bugs, torrents) were complemented by the cloud. The towering masses of clouds in these paintings express protest with a romantic cavalcade of colours – might it be that they forewarn us of the illusion of painted skies?

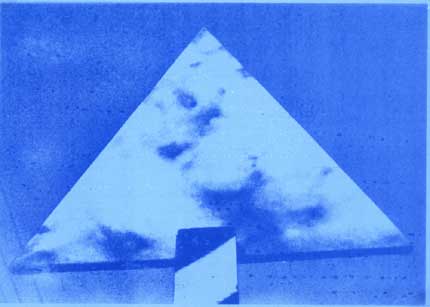

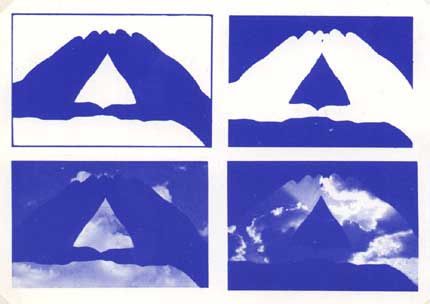

Blown-up cloud drawings of the Cloud Ladder placed in between the rungs – the stations of our potential journey into infinity are clearly modelled on Jacob’s ladder. The Cloud Pyramid (in its painted and objectified versions) is an allusion to the artifacts of great civilizations embodying perfection where, as at a distinguished point of the universe, cosmic radiation is amplified – is it perhaps the heavenly counterpart of these artifacts? Once the artist even climbs into it, as if building it around himself – emphasizing the artist’s individuality does he make himself the vantage point where everything is condensed and from where it is then projected? The Cloud Pillow is absurd: it fondly objectifies what is ungraspable; its softness and puffy triangle quality is a materialization of dreams. Clouds and triangles have continued to be a theme of his paintings: the forms of clouds exuding impersonality on triangle-shaped canvases reappear in devotional, fine and soft colours on the geometrical shapes of his Caleidoscope series, and on a canvas executed with a child’s naiveté, depicting three puffy, colour, fleecy clouds floating on a three-legged easel.

In one of the postcards Lengyel made for the Cloud Museum the viewer can look into the clouds through a triangle shaped by two hands – a blasphemising gesture of trinity – (clouds cover, cover up, and truth is concealed?) and see a starry sky with triangular constellations (Triangulum – the symbol of divine music), and a storm cloud with the vowels of the Greek alphabet before it (the overlap of natural and man-made order, civilisation as the imitation of the laws of nature?). In one of his last works, entitled "Sky over Italy" (1991, Italy), a blue sky is represented. This series revisits his earlier, more romantic cloud paintings, the artistic cloud patterns, and the enlightenment brought on by waiting with an accumulated sense of absence leads on to a clear, bright, blue sky. An open book placed with its pages facing down also resembles a triangle, and although, undeniably, Lengyel’s attraction to books is not rooted in formality their frequent use nevertheless fits in with his conception of triangles.

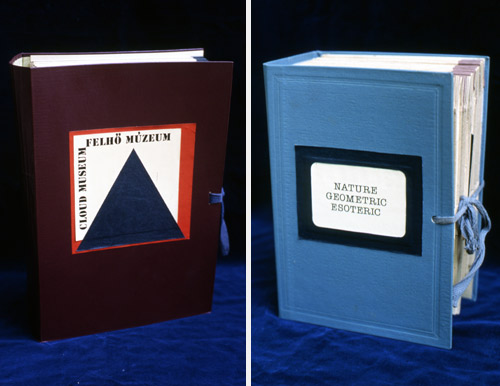

The smallish book-format can be found among Lengyel’s first mail art works and he makes his offset pages as bindable book sheets, too. In his art book, a triangular prism in a black casing placed in-between the colour sheets mysteriously preserves light. Modelled on the Tibetan poti, the sheets of his Rainbow Book are bound with two boards, reflecting the artist’s esoteric interest.

Thus, it is no coincidence that the Cloud Museum also has a book format: an album resembling a folder.

The idea of a small-sized museum derives from Duchamp (his “Portable Museum” contains the small-size copies of his works), whose idea was popular with concept artists since the small size challenges, or questions the idea of a work of art by virtually dematerialising it. László Beke’s Imagination/Idea project and Gyula Pauer’s File Museum (1971) are conceived in a similar vein. This idea was also used by several mail artists, and it was perhaps arranging small-sized mail into a thematic archive that led to the idea of various museums.

Johan van Geluwe’s The Museum of Museums collection, started in 1981, contains postcards of museums for example. The networkers of the second publicity openly made it their aim – using a good amount of irony – to create an institution around their art, equipping themselves with administrative tools to this end and playfully appointing themselves as an institution.

Lengyel made rubber stamps, cloud stamps and even membership cards for the Cloud Museum. Bearing a photograph and signature of its holder these cards pseudo-officially proved someone’s membership in the Cloud Museum.

The name of the Cloud Museum, might seem hard to interpret and perhaps intentionally so: how can the inconceivable and the elusive be captured and arranged in a finite world? However, what we have here is not a scientific systematization of clouds (that is discussed from time to time by the World Meteorological Organisation) but works by mail artists on the theme of clouds. Thus it should come as no surprise that the works are systematized in the alphabetical order of the senders’ names. The items are arranged like in a museum storage and include children’s drawings, paper and cotton ball clouds, a photographic series of Danish clouds (what makes a cloud Danish?), prints, collage works, atomic cloud stamps, computer designs, dream works, a spiral cloud over Budapest, and a non-sterile exemplar not fit for dressing wounds. These works are not covered-in-dust-dead; they are permeated by the scent of communication exuded by mail art pieces.

The Cloud Museum collection is enriched by a number of objects, too, including rainbow-coloured cloud boots (Péter Sarkadi) and a Stone Cloud with a cliché (Róbert Swierkiewicz). The cloud museum and Lengyel’s related collection is a beautiful conceptual game, evoking, true to its pantheistic predecessors, the feelings of man staring at the stars and the sky, seeking for the answers to the questions of the beginning and the end, and standing small in the face of the vastness of the universe:

“The Visible is born of the Invisible.” – Lao Tzu

“We delight in one knowable thing, which comprehends all that is knowable; in one apprehensible, which draws together all that can be apprehended; in a single being that includes all, above all in the one which is itself the all.” – Giordano Bruno

“I stare, therefore I am.” – András Lengyel

See also – Geoff Hendricks: Sky Pillow Cases, Sky Car, Cloud City

András Lengyel and Geoff Hendricks exchanging cloud publications