2014 - the last year of Artpool - ?? | media feedback

17 April 2014, Magyar Narancs [Hungarian Orange] (kislátószög [small angle]), Kriszta Dékei, pp. 30-31

Artpool to be closed down

The power of documentation

Artpool to be closed down

The power of documentation

It seems that Artpool Art Research Center, which was established in 1979 and is Central Europe’s biggest and internationally esteemed collection of contemporary art, will have no choice but to close its doors in 2014. Despite a signed contract with Artpool, the Ministry of Human Capacities has not transferred any support to the institution since January.

In order to understand what a treasure is being neglected (or destroyed intentionally) by cultural policy through closing down Artpool, we should look at the institution’s unique significance – its history.

Spies and stamps

Artpool is primarily the ’brainchild’ of sculptor György Galántai, and its history can be traced back to the Balatonboglár Chapel Studio exhibitions between 1970 and 1973. The chapel – which at the time was no longer used for its original function – served as a venue for premiering works by many members and trends of the Hungarian Neo-Avant-garde, predominantly categorised by the cultural policy of the time as banned, rather than tolerated (members of the Szürenon and Iparterv groups, conceptual artists, geometrical-constructivist "school", as well as action and performance art), complemented by works by many progressive artists of Central Europe. Galántai had a sharp eye for recognising that besides providing the opportunity for trends neglected by the official art policy but linked to international art to "breathe" it was just as important to document them. An important factor in this was the authority’s disapproval of the unfolding underground art of the time: the exhibitions were threatened with uncertainty from the beginning, all the way up to the beheading of the ’hippy movement’ that contravened the morals of socialist society and then led to the existential destruction of the artists. The ’embryonic form’ of Artpool was constituted by the big size flip folders that contained works and reproductions of works that remained at the venue after the exhibitions, as well as photographs of the events (a so-called slide bank), a ’diary’ written by the visitors and the artists of the Balatonboglár Chapel Studio exhibitions, and folders documenting the archived correspondence with the authorities (police, council, public health service). After the change in the political system in Hungary, the latter was supplemented by the reports submitted by spies before the change.

Artpool’s other ’parent’ is Júlia Klaniczay, who György Galántai met in the mid-1970s and later married. The two of them also invented the name of the archive. The concept of Artpool first of all separated Galántai’s activity as the head of an archive of underground art from his activity as an artist, while it also adopted the theory of the genetic pool, which emerged around the time (it refers to a genetic tank in which the gene pool has incredible diversity, from where anything can be born anew). The name also alludes to the Carpathian Basin, and, playfully, to the fact that the window of the flat of the Galántais opens onto Komjádi swimming pool. Moreover, Artpool also became one of Galántai’s ’surnames’ since he was only able to collect mail addressed to Artpool after entering it as his alias in his membership booklet issued to him by the Fine Arts Association.

In order to understand what a treasure is being neglected (or destroyed intentionally) by cultural policy through closing down Artpool, we should look at the institution’s unique significance – its history.

Spies and stamps

Artpool is primarily the ’brainchild’ of sculptor György Galántai, and its history can be traced back to the Balatonboglár Chapel Studio exhibitions between 1970 and 1973. The chapel – which at the time was no longer used for its original function – served as a venue for premiering works by many members and trends of the Hungarian Neo-Avant-garde, predominantly categorised by the cultural policy of the time as banned, rather than tolerated (members of the Szürenon and Iparterv groups, conceptual artists, geometrical-constructivist "school", as well as action and performance art), complemented by works by many progressive artists of Central Europe. Galántai had a sharp eye for recognising that besides providing the opportunity for trends neglected by the official art policy but linked to international art to "breathe" it was just as important to document them. An important factor in this was the authority’s disapproval of the unfolding underground art of the time: the exhibitions were threatened with uncertainty from the beginning, all the way up to the beheading of the ’hippy movement’ that contravened the morals of socialist society and then led to the existential destruction of the artists. The ’embryonic form’ of Artpool was constituted by the big size flip folders that contained works and reproductions of works that remained at the venue after the exhibitions, as well as photographs of the events (a so-called slide bank), a ’diary’ written by the visitors and the artists of the Balatonboglár Chapel Studio exhibitions, and folders documenting the archived correspondence with the authorities (police, council, public health service). After the change in the political system in Hungary, the latter was supplemented by the reports submitted by spies before the change.

Artpool’s other ’parent’ is Júlia Klaniczay, who György Galántai met in the mid-1970s and later married. The two of them also invented the name of the archive. The concept of Artpool first of all separated Galántai’s activity as the head of an archive of underground art from his activity as an artist, while it also adopted the theory of the genetic pool, which emerged around the time (it refers to a genetic tank in which the gene pool has incredible diversity, from where anything can be born anew). The name also alludes to the Carpathian Basin, and, playfully, to the fact that the window of the flat of the Galántais opens onto Komjádi swimming pool. Moreover, Artpool also became one of Galántai’s ’surnames’ since he was only able to collect mail addressed to Artpool after entering it as his alias in his membership booklet issued to him by the Fine Arts Association.

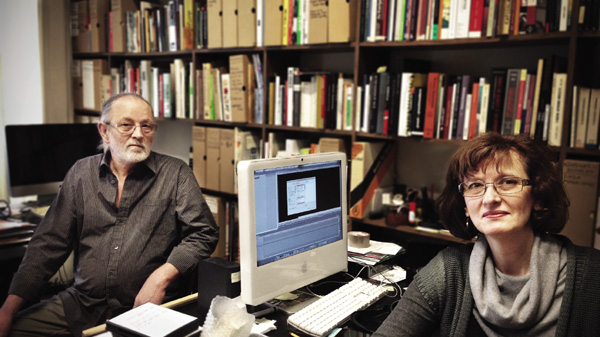

György Galántai, Júlia Klaniczay

Photo: Gábor Sióréti

Artpool’s operation was made possible by the postal service, or more exactly by a postcard made for an international Mail Art exhibition and posted in 500 copies as well as the replies sent to it. But Galántai only regarded Mail Art (art work using postcards, envelopes and stamps complying with the postal standards) as a tool (despite the fact that he was considered to be the most active Mail Art artist in Hungary), a means of communication to be used in Correspondence Art, and a kind of organisational catalyst. It was thanks to the postal service that the Buda Ray University project was realised including the Hungarian and international “responses” to and interpretations of a drawing by Ray Johnson, the actions connected to it (e.g. the Everybody with Anybody rubber stamp action), a telephone concert simultaneously taking place and being heard in Vienna, Berlin and Budapest, as well as the material of the 1984 (banned) exhibition announced with the title “Hungary Can Be Yours!”. Besides organising exhibitions and projects as well as collecting international and intermedial works ousted from "high art", Artpool published a newsletter (Pool Window) from the outset and a – samizdat – periodical titled AL (Artpool Letters) from 1983 to 1985. AL functioned as an arts forum for the underground culture and was an attempt to gather together the contemporary Hungarian art scene as well as provide an opportunity for different views to interact and be documented. The results of these efforts are not only crucially important for the researchers of the art history of the period but also for historians.

Fluxus edition

The changes in 1989 opened a new chapter in the process of Artpool becoming an official institution, not only because the archive finally had the opportunity to move from the private to the public sphere by leaving the flat – that started to resemble a document-cemetery –, but also because in its new identity as a research centre it had new responsibilities added to its operation, such as systematisation, categorisation and making the material available for research. Being pioneers in this respect, they employed young art historians for these tasks, thus also creating the conditions for art history students to conduct their museum internship at Artpool. As a result, the thus far hidden connections in the underground art scene of the 1970s-80s gradually became researchable; moreover, Artpool’s activity expanded and became literally visible (Fluxus banners and texts exhibited on street boards on Ferenc Liszt Square, and Újkapolcs Gallery linked to the Valley of the Arts [Művészetek Völgye]). The various events (discussions, exhibitions) were organised around a new project every year (e.g.: Fluxus, Performance Art, the Internet, the genre of installation, numbers, and the impossible). ’Appearances’ by the ’big shots’ of intermedial genres also took place (including Anna Banana, Geoffrey Hendricks and Ben Vautier). They summed up their activities thus far in an English language catalogue (our review in the column Visszhang [Echo]).

At the moment we have 600 running metres of material available for research. To bring a comparison, Kecskemét College has a Reference Library of Technology and Economics, which occupies three times as large a floor space as Artpool’s archive, and they store 750 running metres of material. Artpool’s material is actually far bigger than this since the backbone of our archive (besides the books and catalogues) is formed by the so-called small prints (invitations, leporellos, artist’s books, posters, stickers, stamps, postcards, envelopes), and it also includes cassettes of experimental music as well as photographic, slide and video collections.

Artpool’s situation is unique in an international context too. Its ’heterogeneous’ collection is open to all materials linked to the underground art scene, unlike, for example, that of the Cavellini Museum, which only receives works about Cavellini, and Enrico Sturani’s collecting approach, which focuses not only on artistic but all kinds of postcards. Many archives of underground art – similarly to the conceptual works that were integrated and/or launched on the art market in the early 1990s – have been purchased by museums (for example, Jean Brown’s Fluxus collection can now be found in the Getty Museum). In recent years, Artpool had negotiations with several public institutions on integration (e.g. with the Museum of Fine Arts and the Petőfi Literary Museum) but ministerial concepts thwarted these attempts.

It is obvious that the ministry’s budget would not be bankrupted by the monthly two million forints support that would be required by the maintenance and operation of the Artpool library, exhibition space, the costs of the storage of artworks and installations, as well as administrative costs, the salaries of the archivist able to assist Hungarian and international researchers, and the various material costs. Taking a positive approach, we could even say that what we have here is merely a lack of awareness or professional competence. But if we look at the situation realistically – considering the processes of annexation and termination of artistic institutions, including those of contemporary art that have been going on since 2010 – we have a feeling that it is not in the interests of the current political power parading itself in the guise of national culture and rewriting history on a daily basis to make an important chapter of the past available. Especially, since it is documented.

Kriszta Dékei

Fluxus edition

The changes in 1989 opened a new chapter in the process of Artpool becoming an official institution, not only because the archive finally had the opportunity to move from the private to the public sphere by leaving the flat – that started to resemble a document-cemetery –, but also because in its new identity as a research centre it had new responsibilities added to its operation, such as systematisation, categorisation and making the material available for research. Being pioneers in this respect, they employed young art historians for these tasks, thus also creating the conditions for art history students to conduct their museum internship at Artpool. As a result, the thus far hidden connections in the underground art scene of the 1970s-80s gradually became researchable; moreover, Artpool’s activity expanded and became literally visible (Fluxus banners and texts exhibited on street boards on Ferenc Liszt Square, and Újkapolcs Gallery linked to the Valley of the Arts [Művészetek Völgye]). The various events (discussions, exhibitions) were organised around a new project every year (e.g.: Fluxus, Performance Art, the Internet, the genre of installation, numbers, and the impossible). ’Appearances’ by the ’big shots’ of intermedial genres also took place (including Anna Banana, Geoffrey Hendricks and Ben Vautier). They summed up their activities thus far in an English language catalogue (our review in the column Visszhang [Echo]).

At the moment we have 600 running metres of material available for research. To bring a comparison, Kecskemét College has a Reference Library of Technology and Economics, which occupies three times as large a floor space as Artpool’s archive, and they store 750 running metres of material. Artpool’s material is actually far bigger than this since the backbone of our archive (besides the books and catalogues) is formed by the so-called small prints (invitations, leporellos, artist’s books, posters, stickers, stamps, postcards, envelopes), and it also includes cassettes of experimental music as well as photographic, slide and video collections.

Artpool’s situation is unique in an international context too. Its ’heterogeneous’ collection is open to all materials linked to the underground art scene, unlike, for example, that of the Cavellini Museum, which only receives works about Cavellini, and Enrico Sturani’s collecting approach, which focuses not only on artistic but all kinds of postcards. Many archives of underground art – similarly to the conceptual works that were integrated and/or launched on the art market in the early 1990s – have been purchased by museums (for example, Jean Brown’s Fluxus collection can now be found in the Getty Museum). In recent years, Artpool had negotiations with several public institutions on integration (e.g. with the Museum of Fine Arts and the Petőfi Literary Museum) but ministerial concepts thwarted these attempts.

It is obvious that the ministry’s budget would not be bankrupted by the monthly two million forints support that would be required by the maintenance and operation of the Artpool library, exhibition space, the costs of the storage of artworks and installations, as well as administrative costs, the salaries of the archivist able to assist Hungarian and international researchers, and the various material costs. Taking a positive approach, we could even say that what we have here is merely a lack of awareness or professional competence. But if we look at the situation realistically – considering the processes of annexation and termination of artistic institutions, including those of contemporary art that have been going on since 2010 – we have a feeling that it is not in the interests of the current political power parading itself in the guise of national culture and rewriting history on a daily basis to make an important chapter of the past available. Especially, since it is documented.

Kriszta Dékei

English translation: Krisztina Sarkady-Hart

2014 - the last year of Artpool - ?? | media feedback