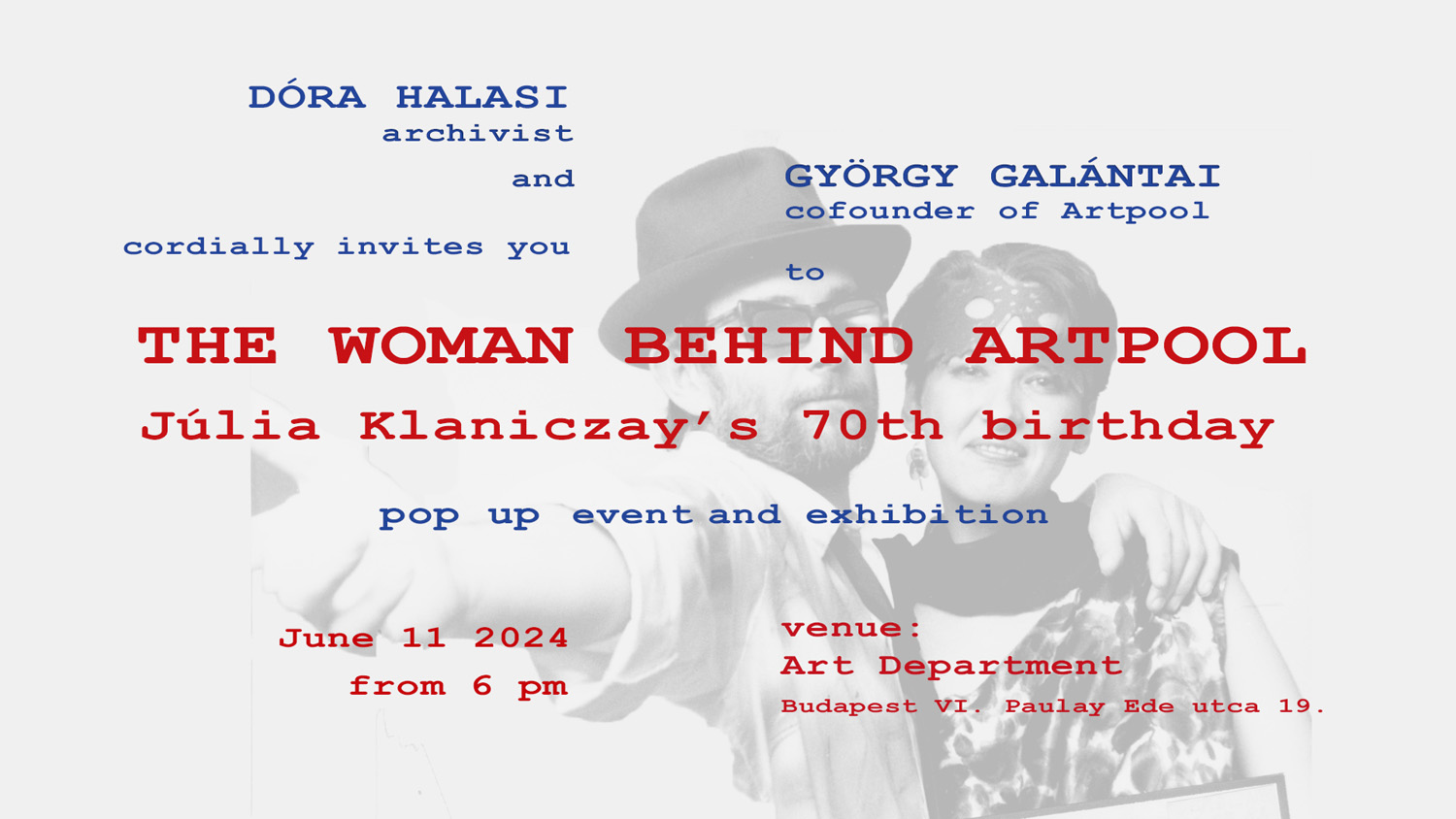

Birthday messages and memories on the occasion of the 70th birthday of Júlia Klaniczay, co-founder of Artpool

András Müllner

The life of the archive and the female surplus

For Júlia Klaniczay’s birthday

Archives do no stay alive, unless they are kept alive. Even those who administered the classical state archiving systems back in the day knew that archives only stayed alive if they changed (grew, expanded and diversified), but they did not accept the life concept (while they were unable to control it), according to which it is not only the archived materials that expands but also the image formed of it(self). Archives stay alive because they are continuously re-inventing themselves; indeed, this happens all the time but it’s often ignored. Perhaps one manifestation of freedom is when those sustaining an archive realise the impact of their ideas on their archive, what is more, they actively “reidealise”, re-conceptualise it, and re-haul the archive as a medium with their concepts (medium rehaul). Júlia Klaniczay knew nothing about all this in 1954 because she was zero years old, although born to an art historian-archaeologist mother and a literary scholar father, she must have heard stories about collecting, archiving and running databases in her childhood. The words archaeologist and archivist have the same etymology: both can be traced back to the Greek term arkhē, meaning ‘originating source’, ‘cause’, ‘principle of knowledge’ and ‘basic entity’. At the same time, establishing an archive is an act of creation, that of separating things worth being archived from those that are not, which is not a single act but continuous acting – at least in the concept of the living archive. Establishing an archive is in the present continuous: those looking after an archive, recreate it again and again.

The creation of an archive is often only associated with spectacular actions. While these play a fundamental role in continuously reviving and sustaining the archive, a less spectacular gestures of creation should also be remembered: those that provide the basis for the archive, as it were. In the following, I will discuss an allegorical example of this, and, importantly, address the issue of the invisible female contribution; indeed, more than addressing the subject, I will place this kind of work at the focus of my example.

The activity of Artpool, founded in 1979, began with a museum visit (I believe it was no coincidence), taken by the founders to Guglielmo Achille Cavellini’s self-museum in 1979 as a first step in their international networking activity. The Cavellini connection continued in 1980 in Budapest: a Cavellini exhibition was organised, and a living statue project, the Mukhina Project, was realised on Heroes Square, with György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay performing the living statue, and Cavellini playing a prominent part in the statue being transformed into a performance act. In the interview volume titled The Mukhina Project. Interpretations of Being in György Galántai’s Oeuvre, Galántai discusses the context and implementation of the project in detail. He talks about how the Mukhina Project could have not been realised without Cavellini’s conceptual method of self-historicisation. Cavellini was important not only as an inspiring master in this project but also as one of its participants, who extended self-historicisation (writing himself into the history of art) to Galántai.

“The Mukhina theme continued in Budapest because at the time I thought that if according to the Hungarian state’s official point of view we had ‘developed socialism’ in the eighties, then, corresponding to this possible reality (or just testing reality), I could be a ‘developed socialist realist artist’.

While preparing the correspondence material and working on the Cavellini exhibition, I was trying to think how we could spend the time with Cavellini. We needed another joint event. Then I came up with the idea of Cavellini’s inscribed coat, i.e. a clothes action! We had white shirts, white vests and trainers but no white trousers. It may seem pretty strange now but in the ‘shortage economy’ of advanced socialism you could only buy white trousers in summer! Luckily, Julia Klaniczay could sew so we had all the clothes for the action which Cavellini then inscribed. Julia wrote to him about the action we were planning and where we wanted to perform it so he prepared for it and brought everything. A fundamental prop we still needed for the Mukhina Project was a little book on socialist fine arts with a page showing the reproduction of Vera Mukhina’s sculpture; we held this in our hands in the action.” (p. 23, p. 31)

Galántai also talked about Cavellini’s role:

“Cavellini had a little triangular sticker with the names of artists symbolizing the history (development/evolution) of art. It started at the top with Altamira and ended at the bottom with Cavellini. He sent me an altered version of this with Artpool – Cavellini – Galántai in the bottom line. This is how it became a new meme in the meme complex. I suggested that instead of the usual Cavellini self-biography – and of course in connection with the place of the action – that we should inscribe the clothes with a system listing the greats of art history, which Cavellini accepted. However, he decided what names and what order he would write them in. He began the inscribing by writing the names Cavellini and Galántai at the top, on the shirt collar.” (p. 31)

So, Cavellini inscribed the living statue, the white clothes worn by György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay with names of artists. The names of Cavellini and Galántai were at the top of the evolution, followed by virtually only male names – which, factually speaking, is characteristic of art history. If we look carefully, the male and female work were distinctly separate in this living state action: a female work (done by Klaniczay) was to create (sew) the white clothes, the passive, receptive surface suitable to be inscribed, while the male work (done by Cavellini) was the inscribing, i.e. the act of leaving a mark. At the same time, as Galántai pointed out, the two of them, he and Klaniczay, were together as one in creating the statue in several ways, almost like each other’s mirror images:

“In the ‘living statue’ with Julia Klaniczay, she and I were not only together but also as one: we were holding the same object (the book), which connected us, and Cavellini did not write the names on us separately but continuously on both of us, line by line, from top to bottom. In this way, the symbolism of cooperation between man and woman was more complete than in the original Mukhina statue.” (p. 33)

The reason I wrote that they were almost each other’s mirror images is because Galántai’s shirt had a collar, while Klaniczay was wearing a collarless white T-shirt. I could say the collar was the ‘male’ surplus, the part missing from the woman’s top that provided the extra surface on which the men’s names, representing the peak of evolution, were written. This is the small detail why this was not the case of complete mirroring: the seeming balance was tipped by the ‘male part’, the lack of which on the female body appears to be the consequence of castration, the loss of power and strength. There is also a surplus, a pair of glasses, on the female face, which might as well restore the balance, but a pair of glasses – an extension or medium, to use McLuhan’s concepts – is an indication of the shortage of something: it is the sign of incomplete vision, in other words: short-sightedness. The gender check, i.e. the gender-based interpretation of the living statue of the Mukhina Project, confirms the lack of power balance between the sexes: the dominance of the male side, characterised by a surplus, and the subservient nature of the female side, characterised by absence.

That is, if we do not look for other interpretations. According to one possible interpretation, the inscriptions could not exist without the white, so-called passive surface. The list of the greats of European art history, which is the same as the archive of the names of the creative male artists, could not have been compiled without a suitable surface. The foundation of the archive was preceded by another, albeit invisible, foundation: “Luckily, Julia Klaniczay could sew so we had all the clothes for the action”. Sewing itself is ‘writing’ in a metaphorical sense: it was the ‘writing’ that preceded the inscribing. The surface is always a surplus, since it contains what is written on it: if it were not, then writing would overspill into space and it would not be visible there as writing. The creation of a surface (its incision and montage-like assembly) thus precedes the act of inscribing. This interpretation is confirmed by another trace of the text, which, similar to sewing, is an act of pre-writing, or pre-foundation. “Julia wrote to him [Cavellini] about the action we were planning and where we wanted to perform it so he prepared for it and brought everything.” If Klaniczay had not written what she had (obviously agreeing it with Galántai), Cavellini could not have “prepared for it”, and the compilation of the list – an archive-creating act that formed part of the performance – would have never happened. This other pre-writing is again an act of communication conveying a surplus which remains in the dark as it is not given publicity within the more strictly defined action, even though it absolutely forms part of its context; moreover, it is the act of its pre-foundation. Contexts like this are virtually matter-of-factly not included in the photographs taken of the action and its exhibition. And even if they are, such as in the book on the Mukhina Project, the reader must scrutinise the pages, so to say, to find them in-between the lines. To find the female strength, which we can present as a surplus, from now on/always.

András Müllner

(2024)

Bibliography

Júlia Klaniczay (ed.)(2018): A Muhina-projekt. Létértelmezések Galántai György életművében [The Mukhine Project. Interpretations of Being in György Galántai’s Oeuvre], Budapest: Vintage Galéria. (book review; download the pdf)