Kornelia Röder: Ray Johnson and the Mail Art Scene in Eastern Europe

in: Kunsttexte.de, 3/2014

Introduction

The 1983 video Zone,[1] by the artist Jakobine Engel, was recorded secretly in the underground station between East and West Berlin before the wall broke down. ‘Zone’ was an insulting term for the Eastern Part of Germany, and this metaphorical expression gives an idea of the real situation with its lack of communication and understanding during the time of the Cold War. Likewise, the dark tunnel with the lightning spots could be read as a metaphor for the importance of creating an independent network of communication and exchange between the two parts of the world and their different political systems.

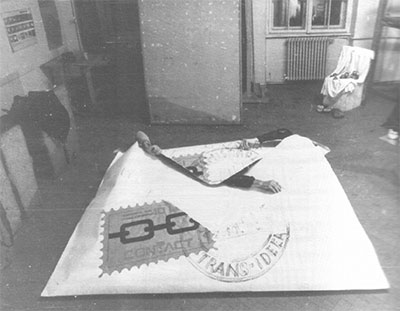

1. Doru Tulcan and Iosif Kiraly, Timişoara, TRANS IDEEA, Performance, October 1982.

The artist Guillermo Deisler, who emigrated from Chile to East Germany in 1986, described the importance of the network of mail art, he called it a window to the world. The performance TRANS IDEEA by the artists Doru Tulcan and Iosif Kiraly from Timişoara (fig. 1) visualised the feeling of many people in the countries of Eastern Europe. These Romanian artists put themselves in a large envelope with stamps, postmark and recipient’s address. To understand the importance of the network it is necessary to emphasize the real life of Eastern Europeans. It was determined by the lack of basic rights like the freedom of thought, of press, of assembly and travel. Censorship ruled all publications like newspapers, books and magazines. The public media - as in TV or radio - was under control of the government. The artistic scenes of theatre, film and fine art were monitored by the state. To print exhibition catalogues and even postcards, you needed official permission. Human rights, which exist in democratic societies, were restricted. Mail control and observation by the intelligence service were everywhere.

In contrast, within the world of the mail art network, the Iron Curtain was more a net with large meshes, because the artists were very inventive. It was a dangerous game with the power of state authorities.

The aim was to be quicker and smarter. Birger Jesch for example used envelopes normally carrying letters of condolence. Paweł Petasz sewed his letters in order to prevent them from being secretly opened by steam. Endre Tót and many others mailed their letters from different cities and/or several times in the hope that one would arrive.

Ray Johnson’s importance for the development of an international network

“I think the New York Correspondence School was truly communicative simply because I was able to wheel the ping-pong paddle and to keep the ball on the move...”[2] - this was the idea of the American artist Ray Johnson (1927-1995).[3] During recent years, a number of catalogues and exhibitions have appreciated his achievements. The exhibition RAY JOHNSON: PLEASE ADD TO & RETURN in the Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA),[4] which finished in February 2010, acknowledged Johnson’s significance as a “key element for the understanding of an epoch and a way of approaching the relationship of the artist with the artistic community of New York.”[5] In my opinion, Johnson's activities and ideas were also the key for the development of the international mail art network, which included Eastern Europe. Perhaps his influence was not a direct one, but he still had an enormous impact, which inspired the Eastern European artists. In the following paper, these complex interrelations shall be outlined.

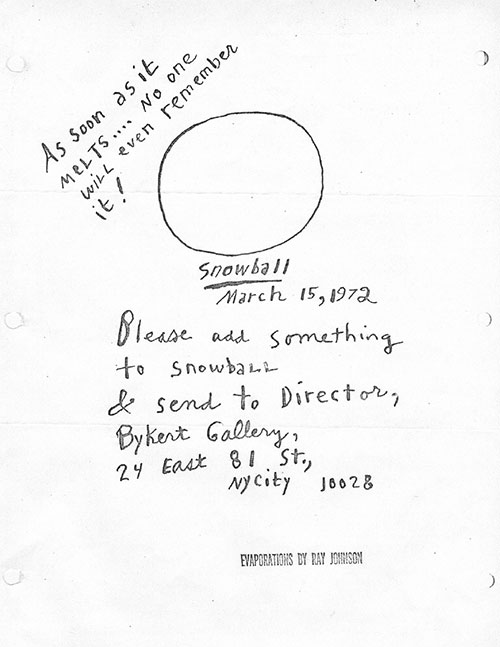

Ray Johnson created different forms of dialogues, literally with the material of his art. PLEASE ADD TO & RETURN formed a new way to receive art without the involvement of any institutions like museums or art market oriented galleries (fig. 2). He created an anonymous cycle of distribution and feedback between the artist and the recipient, thus investigating complex communication with changing images. Exploring the system of the art market and everything belonging to it, Johnson opened the closed system between artist, mediator and consumer, and created an alternative.

Eastern Europe did not have an art market, but instead its world of art was shaped by ideological usurpation and censorship. Thus, Eastern mail artists focussed particularly on those topics that were banished from public discussion. In this regard we can find lots of parallels between East and West. Topics like freedom of art and creativity, new forms of art, sociological problems, environmental pollution and acceptance of differences were the main subjects. The spirit of blurring the boundary between life and art united artists and people interested in the network. A counterculture generation was looking for new ways for artand life. Ray Johnson’s collages, drawings and various mail art media were understood as hints at his personal ideas for a popular culture and his view of the art world.

Thereby, Johnson created a complex network of opinions. The main subject of his work was to annihilate the differences between the professional artist and the amateur. By opening the network to all people he removed the strict academic ways of the art market. Everybody was able to participate. This particular aspect of Johnson’s idea formed the basis for the mail art network. The structure of the network guaranteed the abscence of any form of hierarchy of exlusion. Its credo was „No jury, no fee, no return.“

2. Ray Johnson: Snowball, 1972.

Ray Johnson was known for his self-mockery. He curiously observed what happened within the system of corresponding exchange, developing and inspiring one of the first network formations in the context of art. His Correspondence Art generated new forms of interpersonal communication, which were also characteristic of the mail art network. His activities made no distinction between life and art. Johnson invented communication as a form of art long before Fluxus and other art movements appeared.

The invisible process of networking and an attempted reconstruction

Ray Johnson never visited Eastern Europe, but his ideas of networking crossed continental borders. The fascination with international communication and the exchange of ideas rose worldwide. The American art historian Mark Wikley describes the spirit of that time as “Network Fever.”[6] A lot of new artistic and creative ideas like Performance, Happenings, Conceptual Art, Concrete and Visual Poetry were born at that time. The borders between the classical media of art melted away. Interaction and multi-disciplinary working brought another understanding of the question: what is art? These new art forms needed a new system of communication, distribution, and another approach to reach the audience. The network offered all those opportunities. Counterculture movements, especially, discovered in it a place for action, creativity, communication, distribution, and collaboration with others in the sense of Ray Johnson’s PLEASE ADD TO & RETURN.

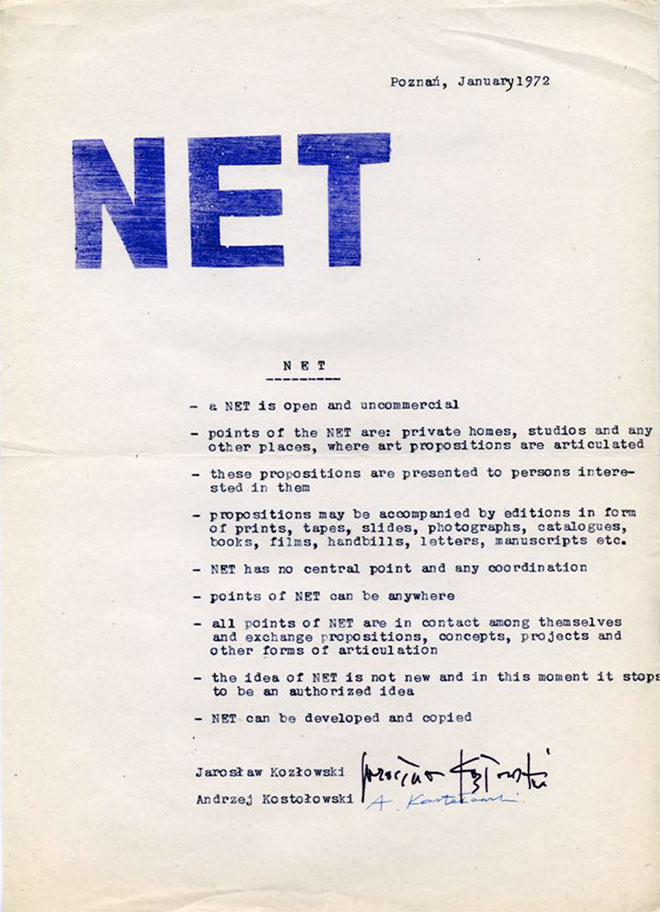

3. Jarosław Kozłowski, Andrzej Kostołowski (Poznań, Poland), NET, 1972.

The first evidence of relations between Johnson and artists from Eastern Europe can be found in the International Image Exchange Directory, which was published by the Canadian artist group Image Bank in 1972. Johnson only travelled twice outside the United States in his life. On both occasions it was to Canada. In 1969 he travelled to Vancouver in order to participate in the UBC Fine Arts Gallery exhibition Concrete Poetry, which included a collection of his collages. In 1973, he visited General Idea in Toronto, whose FILE Magazine documented the correspondence network.[7]

Image Bank published the International Image Exchange Directory in 1972. The entry referring to Ray Johnson included his address in New York and the following statement: “Requests photos and info on Shirley Temple and Shirley Temple dolls, plus alphabets.” From Eastern Europe, the following artists were included: J.H. Kocman (Brno), Petr Štembera (Prague), and Jiři Valoch (Brno), as well as the Polish artist Jarosław Kozłowski; all of them with the remark: “Would like to be on your mailing list.”

Building international files with addresses was crucial to the process of networking, because contacts were the entrance to the network in the days before the internet. The Bill Wilson archive (New York) and the Jean Brown collection (The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles)[8] include mail art works by Eastern European artists. These people and their collections shape nodes in the process of networking, which have not been fully researched to date.

In 1971 the Polish artists Jarosław Kozłowski and Andrzej Kostołowski formulated NET, a theory of the invisible process of networking (fig. 3).[9] One year later it already circulated in the network of mail art.

NET displays remarkable parallels to Ray Johnson’s ideas. According to Kozłowski and Kostołowski, NET is open and non-commercial. While existing outside institutions, it includes private homes, artists’ studios, and other places where artistic ideas are born. Proposals are directed to those who are interested. They are accompanied by publications, the form of which is arbitrary. NET has no central point and no co-ordination (a construction that stresses the non-hierarchical aim). The knots of the net are located in various cities and countries. The contact between these different knots comes into being through an exchange of concepts, projects, notations and other methods of articulation. As a result, a parallel exhibition at all points is possible. Kozłowski and Kostołowski state that the idea of the NET is not new; once it has surfaced, no author can be indicated and the NET may be used and reproduced at will. As the above statements show, the manifest NET declares essentials for creating networks, and being the first theory of network in the context of art, it is still of great importance up until now. Although NET and the ideas of Ray Johnson were created in totally different political and social systems, they formulated similar alternatives in developing new positions in art.

The beginning of the cooperation between Ray Johnson and Artpool

Johnson's ideas about art as communication inspired the Hungarian artist and organizer György Galántai. He and his wife Julia Klaniczay initiated a lot of projects in relation to the creative ideas of Ray Johnson.[10] The following statement by György Galántai from 1989 points out what fascinated him about Correspondence Art: “After all, Correspondence Art is a sort of brainstorming that makes it possible for us to find out what people are interested in and what the answers are.”[11]

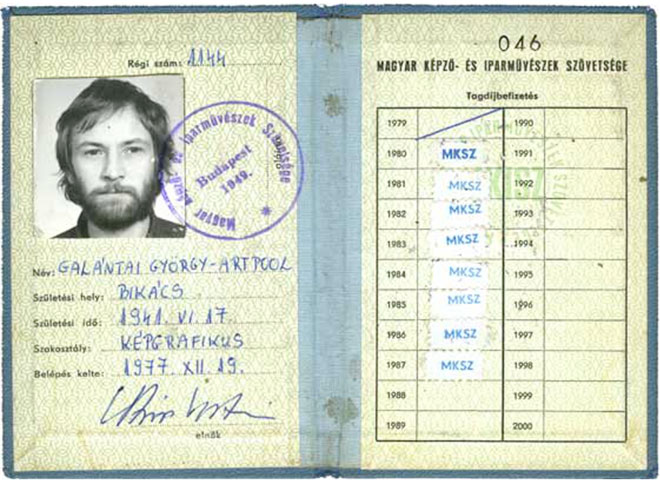

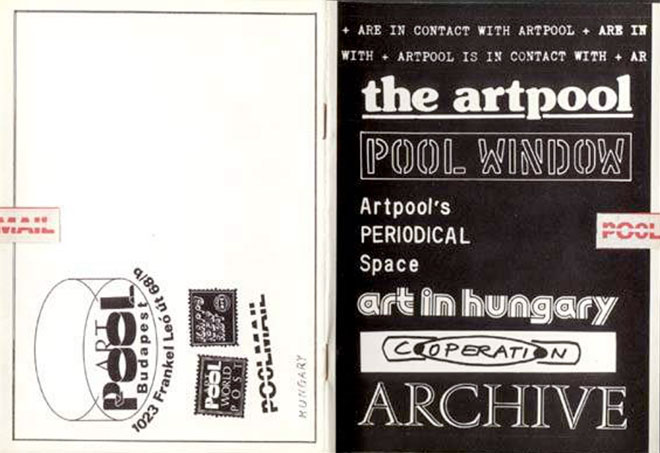

With the foundation of the Chapel Studio in the beginning of the 1970s, in a small lakeside village in Hungary, Galántai established a place outside of the official state art system. The police closed his studio in 1973. Such communicative meeting places were suspicious to the state and therefore controlled or, even worse, shut down. Suppressions like these were quite common in Eastern Europe. Yet the Galántais were not frightened and founded Artpool in their studio in Budapest in 1979. As a result, the Post Office refused to deliver the registered mail that was addressed to Artpool to Galántai, but undaunted he asked the Arts Foundation to register Artpool as his professional name in his membership card (fig. 4).

From 1980 until 1983 Galántai and Klaniczay published Pool Window. It was a one-page newsletter containing information about exhibitions, galleries and other activities, in and outside of Eastern Europe, as well as invitations to mail art projects. The Artpool archive operated as an underground institution with an international orientation. It became the most important documentation centre of alternative movements in Eastern Europe and especially in Hungary (fig. 5). Galántai and Klaniczay collected not only mail art, but also the most diverse cultural statements, such as music cassettes and video recordings as well as publications of experimental literature and documentations of political subcultural activities.

A letter by Johnson referring to the second drawing reached Artpool with the message “Thank you for all your communications” and a Dora Maar Fan club stamp. After that another one arrived with a Yoko Ono Bunny stamp. In 1983 a letter followed with the fourth drawing, and Johnson expressed his gratitude. Once, he finished a letter with the request “send it” to the German Peter Below and added a drawing with a duck in a cloud and the comment: „DUCK CLOSE” and wrote: “OH BOYS ALWAYS THE SAME STYLE.”

Having outlined the general development of the network idea in Eastern Europe, triggered by Ray Johnson, I am going to focus next on particular projects. The contact between Galántai and Johnson was not established without difficulties. Galántai received Johnson’s mail address from Romano Peli in Parma (Italy) in 1979. He contacted Johnson, who did not answer the letters. Three years later Galántai tried to get in touch with him again. He made twenty postcard collages and sent one per day to Ray Johnson.

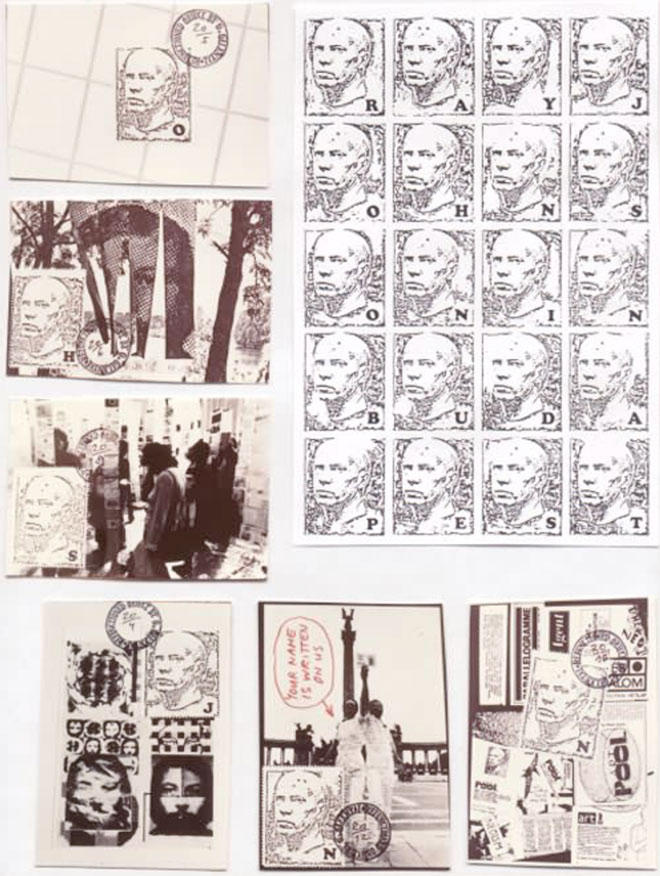

One of them shows the performance Homage to Vera Mukhina, with which György Galántai and his wife Julia Klaniczay criticized the pathos of the Socialist realism from the Soviet Union, a style which served as dogma for the official art in Eastern Europe (fig. 6). After this postcard action, Johnson answered with a first ‘send to’ letter containing drawings. Galántai modified these drawings and multiplied them. After this transformation the drawings were sent to all of Artpool’s mail connections and then back to Ray Johnson. In the following month Johnson posted further drawings.

Thus, a real cooperation started. More and more people, even people formerly unknown to György Galántai and Julia Klaniczay, took part in the evolving communication. Exchanged letters like the following example demonstrate how the network spread.

A letter by Johnson referring to the second drawing reached Artpool with the message “Thank you for all your communications” and a Dora Maar Fan club stamp. After that another one arrived with a Yoko Ono Bunny stamp. In 1983 a letter followed with the fourth drawing, and Johnson expressed his gratitude. Once, he finished a letter with the request “send it” to the German Peter Below and added a drawing with a duck in a cloud and the comment: „DUCK CLOSE” and wrote: “OH BOYS ALWAYS THE SAME STYLE.”

4. György Galántai: Membership card, 1979.

Artpool Ray Johnson Space

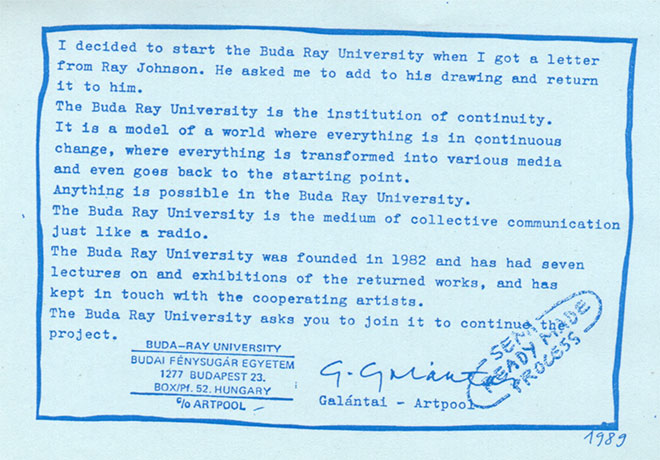

Johnson’s Buddha University was one of the incarnations of his New York Correspondance School, which was closed in 1973. The Buda Ray University was Galántai’s invented background institution for the creation of Artpool’s Ray Johnson Space (fig. 7). The Hungarian artist decided to found the Buda Ray University when he got a letter from Ray Johnson with the request to add something to his drawing and return it to Johnson. The word ‘Buda’ stands for the hilly part of the city Budapest, where György Galántai and Julia Klaniczay lived, as well as for Budapest itself. The university was founded in 1982 in homage to Ray Johnson. Galántai described the Buda Ray University as an

“institution of continuity, as a model of a world where everything is in continuous change, where everything is transformed into various media and even goes back to the starting point. Anything is possible in the Buda Ray University. The Buda Ray University was understood as a medium of collective communication just like a radio.”[12]

5. Artpool: Pool Window, 1982–1983, Newsletter.

Seven lectures were organized. Galántai remembered: “Here, as in real life, one keeps switching roles. For there are two people in all of us: the teacher and the student; thus there is no difference between teacher and student. Every member of the university asks and answers questions. The questions and answers are visual.”[13]

He prepared exhibitions of returned art works by cooperation partners. During the six years of the project, Johnson himself took part in it only once. He informed all the people who were on his mailing list about the activity. The Buda Ray University gained more and more participants through the continuous posting of the first four letters. Two books concerning Johnson's activities were result. One of them was Artpool’s Ray Johnson Book/ Four Letters[14] from 1985. It was photocopied on 120 pages size DIN A4 and issued in a limited edition of ten.

The other was a booklet named To live in a negative Utopia,[15] which appeared in 1987. It contained a selection of answers to Ray Johnson's second ‘add to’ letter. Thirty-two artists took part in this project. The book enclosed thirty-four photocopied DIN A5 pages. One hundred numbered copies were produced. In 1988 Ray Johnson thanked Artpool for this publication and asked Galántai to send Clive Phillpot, from the library of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a copy. Moreover, Johnson encouraged Artpool in this letter to send Phillpot further material. These two examples show the way in which the network spread out and how people got into contact with each other.

6. György Galántai: Postcard collages, 1982.

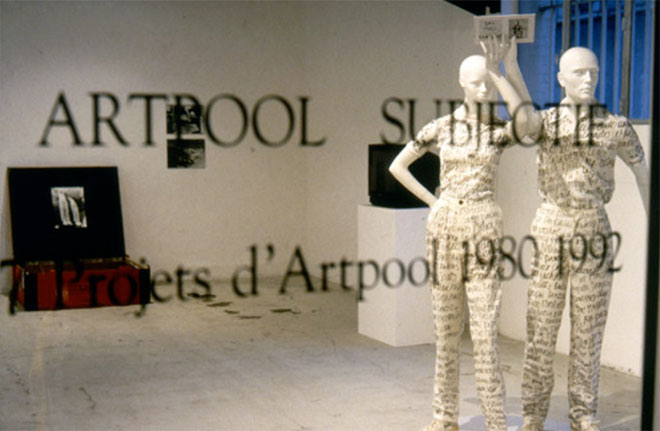

Two noteworthy aspects emerge along with this analysis: Firstly, Artpool established ties to well-known institutions and researchers on the basis of the connection to Ray Johnson. This fact must not be underestimated because the international exchange was restricted in Eastern Europe. The second aspect is the importance of alternative publications. They are absolutely crucial for the network of mail art. The network served not only as a space for communication and exchange, but also as a possibility to edit books, magazines and new forms of publications like assemblings. For East European artists the opportunity to publish within the network was very attractive because they were able to print material beyond the state control and the alternative art scene had thus found a medium to present their artworks internationally. Leading to the establishment of Artpool was one of the most successful projects based on five drawings by Ray Johnson from 1986 entitled BILL de KOONING'S BICYCLE SEAT. The project was initiated for the Ray Johnson Book, and the bicycle seat was a reference to Marcel Duchamp’s first ready-made Bicycle Wheel. Artpool received many reactions to the ‘Bicycle seat’ within a short time. Since the material was too big to turn it into a book, Galántai chose another form of publication: a series of exhibitions. The chronology of the Artpool’s Ray Johnson Space gives an idea of the activities during that time. Between 1986 and 1993 it was shown fourteen times in eight different countries all over the world. Sometimes it was part of other events, sometimes an independent exhibition.[16] Besides mail art, the exhibitions combined presentations with visual poetry. They were presented in connection with European festivals or as activities against current art (fig. 8). Topics of some projects included in the Artpool exhibitions encouraged participants to think about a new relationship to Marcel Duchamp’s art. Duchamp as well as John Cage or Merce Cunningham was one of the main, important figures pioneering new art movements in the 20th century. Duchamp’s concept of the readymade had broken with all conventions in art already in the beginning of the century, yet for a long time Eastern European artists could not experience his artworks directly. Neither were Duchamp’s works present in museum collections, nor were any of his exhibitions presented in Eastern Europe. Furthermore, it was difficult to obtain catalogues or publications.[17]

7. Galantai György: BUDA-Ray University, 1989.

Projects like In the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, initiated by Artpool in 1987, however, stimulated the discussion about his revolutionary understanding of art among the participants of the mail art network (fig. 9). Duchamp’s influence on Eastern European artists, which to my knowledge worked mainly via the mail art network, requires further research.

Ray Johnson’s influence on the worldwide network activities including Eastern Europe

8. Artpool Subjectif – 7 projects d'Artpool, Budapest, 1980-1992.

Ateliers d'artistes de la ville de Marseille, 1993, France.

The correspondence between Johnson and Artpool seemed like a ping-pong game - forwards and backwards with important and long lasting inspirations. In 1988 Johnson announced his own death in the near future. He drew with chalk his name, date of birth and death and signed with “MR. MONTAUK”. In 1990 the Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo published an off set print with a portrait of Johnson in his youth, which had been circulating for a long time in the network. Three years later Johnson sent Galantai a drawing:

“BEST WISHES AND MUCH LOVE FROM THE NEW GUINEA CORRESPONDENCE SCHOOL/ BIANCA JAGGER IS MY FAVORITE FLUXUS ARTIST.”

On the verso there was an offset-print of the drawing by Willem de Kooning.

The name of Ray Johnson is associated with the beginnings of the Fluxus movement. Ray Johnson studied at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he became acquainted with Willem de Kooning, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller, and Robert Rauschenberg, among others. After finishing his studies, Johnson moved to New York. For his art works he used fragments from popular culture. Johnson favoured the Lucky Strikes logo and images from fan magazines with movie stars like Elvis Presley, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe and Shirley Temple. His collages are an example of Neo-Dada and the beginning of the Pop art. Since 1955 Johnson had been calling his short collages Moticos. At the same time he started his first happenings. Between 1957 and 1963 Johnson participated in performance art events and in the Fluxus Yam Festival of 1963.

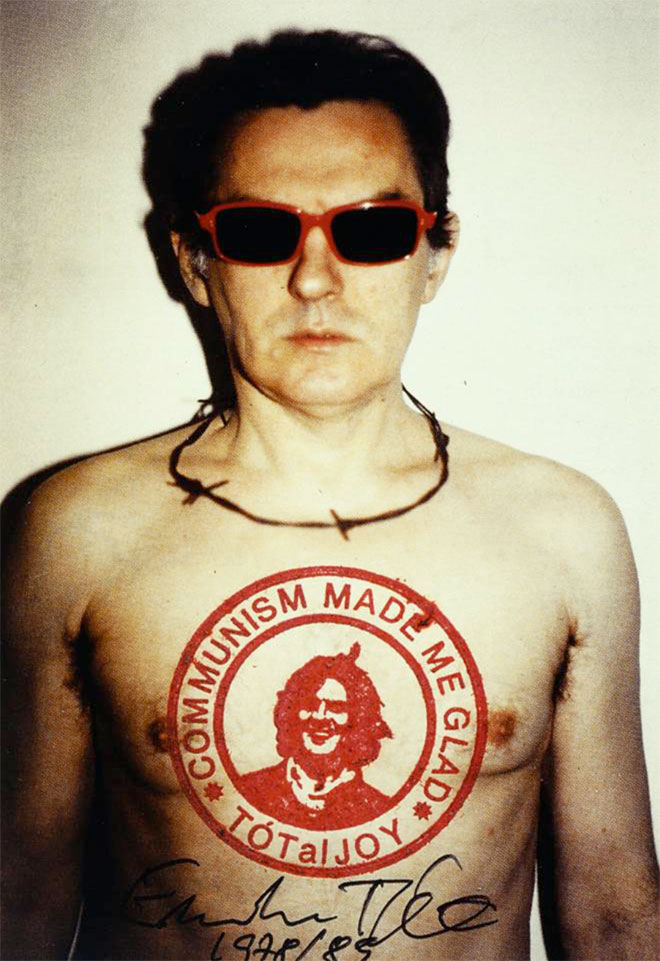

Galántai also considered himself a Fluxus artist, yet his opportunities to enact happenings publicly were severely restricted, as was the case in all Eastern European countries. Fluxus’ activities were directed against the art establishment, and meant to overcome the boundaries of art by developing new forms of interdisciplinary work and interaction with the audience. Similar artistic positions developed in Eastern Europe using the network of mail art as a main (resonance) space for actions. According to my research, Galántai, Robert Rehfeldt, Endre Tót and other East European Fluxus artists used the medium of mail art to make their position known within the Fluxus movement (fig. 10). Galántai, for example, communicated all his underground activities such as video, performances, radio and sound art through the network.

These facts taken together led to the German art historian Eugen Blume’s conclusion that Mail art in Eastern Europe could be called the pilot flame of Fluxus.[18] Another collaboration between Johnson and Artpool took place in 1994, when Johnson took part in Artpool's Hands-project. He drew a round hole in the palm of the depicted hand, which was originally sent by Galántai. Artpool answered by filling this hole with J.O. Olbrich's consignment of the same day. A second contribution from Johnson to the Hands-project got to Artpool. It was a cut-out combined with a frottage on the envelope. In reply, Artpool continued the process of communication and networking. Two envelopes from John Held Jr. and Robin Crozier arrived on the same date and were added to Johnson’s letter.

There are numerous examples of the worldwide network activities of Artpool with artists, mail artists and famous museums like the Musée de La Poste in Paris. It is important to recognize the function that Ray Johnson conferred on Artpool in this respect. It advanced to the central transmitter in a communication, developing globally and crossing country borders. With the support of Ray Johnson, Galántai's contacts were multiplied, and likewise for all participants. Johnson opened the dialogue and communication process that normally exists between correspondents. Even after the death of Johnson this spirit continued with real projects.

9. György Galántai: Mail Art-Project: In the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, 1987.

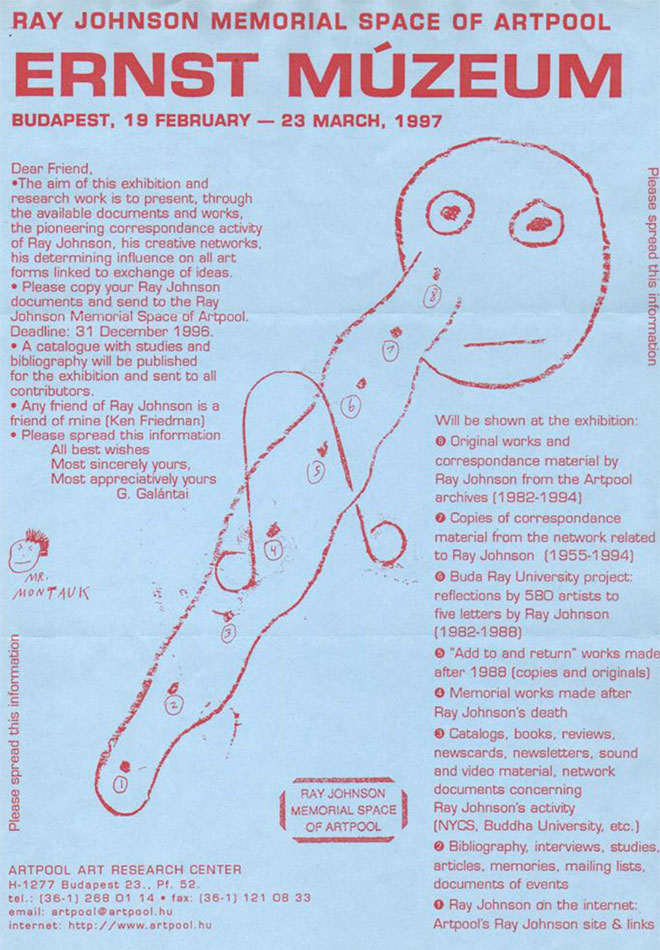

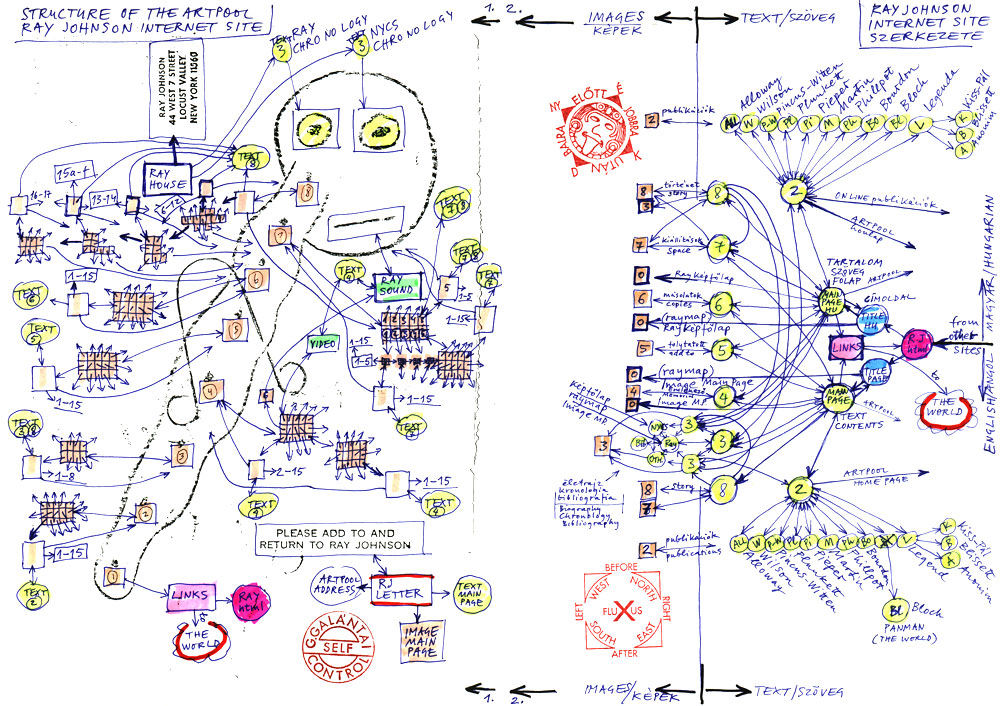

In 1997 Artpool organised the memorial exhibition Correspondence Art of Ray Johnson. It was presented in the Ernst Muzeum in Budapest (fig. 11). Besides memorial works, the exhibition contained catalogues, books, reviews, newsletters, sound and video material, network documents, interviews, mailing list and much more. Artpool’s website concerning Ray Johnson, which is based on this exhibition, can be considered itself as an artwork by Galántai.[19] The composition and the design of this website permit all internet users a lively insight into the intensive relationship between Ray Johnson and Artpool.

Conclusion

György Galántai wrote in 1989:

“The art that is spread all over the world through the network has arteries and pumps enhancing the flow, the circulation. The practice pursued by Ray Johnson and, in parallel, by the group of artists called Fluxus, according to which art can also materialize in relationships or as a function of real life, has become a fundamental concept now, at the end of the century.”[20] [21]

10. Endre Tót: Stempelaktion, 1978/89.

Today ‘network’ is a ubiquitous term and can be used in various contexts. At the time when the mail art network evolved, it was a new way to communicate and exchange ideas across borders. For Eastern Europe it had a special function. The activities of Eastern European mail artists were directed against the ideological occupation of art. The network helped artists to evade censorship and state restriction and thus to maintain and preserve artistic freedom. Since the network was especially used by artists of the countermovement, the circulating works as well as the initiated projects offer an insight into the alternative art scene of the various countries. Because of the network’s invisibility, its participants were able to partially elude the state-run control mechanisms and create subversive structures.

11. Correspondence art of Ray Johnson, 1997.

The knots and strings - or the “arteries and pumps” - as Galántai named the structure of the network, can be reconstructed with the material, the contributions in projects, books, magazines and in the archives of many mail artists all over the world (fig. 12). Therefore, the network of mail art was an autonomous communication system and stayed independent of governmental and commercial media. Even thought it could not make up for the existing information and communication deficits in art and society as a whole, it was a major factor in the information flow between East and West and the other parts of the world. The network gave artists and people interested in communication the chance to exchange their works and ideas. For Ray Johnson networking was an artistic strategy, creating alternatives to the existing forms of production, distribution and communication.

12. György Galántai: Structure of the Artpool, Ray Johnson Internet Site.

Moreover, in Eastern Europe the network gained an existential dimension. It became part of an intellectual and artistic survival strategy for many of the participants. Concerning the relationship between Ray Johnson and Eastern Europe, we are still at the beginning of research. Artpool’s connections to Ray Johnson were most important, direct and materialized in many projects. Other well-known mail artists like Paweł Petasz had contact with Johnson only sporadically. Lutz Wohlrab, an active mail artist from the former GDR and today an editor of public ations about mail art, started an inquiry about the connection between Ray Johnson and the East German mail artist scene. His project could not verify any contacts.

Independence from the art market or, as in Eastern Europe, independence from the state generates the basis for the freedom of art. The New York Times reporter Grace Glueck characterized Ray Johnson after his collage exhibition in 1965: “Ray Johnson is the most famous unknown artist in the world,”[22] thus referring to the relevance of artists creating self-organized communication media to reach the public. In this respect, Johnson’s view coincides with Duchamp’s who said: “The great artist of tomorrow will go underground.”[23] Both statements demonstrate the transformation in the self-understanding of artists. Marcel Duchamp and Ray Johnson, as well as Fluxus artists, wanted to unite art and life again. The following statement by Marcel Duchamp could be also understood as the credo of György Galántai:

“I like living, breathing better than working. I don't think that the work I've done can have any social importance whatsoever in the future. Therefore, if you wish, my art would be that of living: each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral, it's a sort of constant euphoria.”[24]

An interlinked world and connected people were the intention of Ray Johnson’s activities and have now become reality. The speed of the networking process accompanying globalization has brought profound changes for everybody. Today still, artists research and use networks in various ways. Ray Johnson’s ideas are living.

Endnotes

The essay is a revised and completed version of a lecture held at the CAA 98th Annual Conference in Chicago, 10-13 February 2010, at the panel: How to draw a bunny (Chair: Steve Perkins). The text was translated by Claudia Schönfeld and Thomas Röder as well as copy-edited by Mark Deavin and Antonia Napp.

__________________

[1] See further: artfacts.net.

[2] Ray Johnson, Correspondence Art of Ray Johnson, ed. Artpool, Leaflet for the exhibition in the ERNST MUSEUM Budapest, Budapest 1997

[3] See further: rayjohnsonestate.com.

[4] The exhibition was open between 5th November 2009 – 10th January 2010. Curated by Alex Sainsbury, Chus Martínez.

[5] See further: macba.cat.

[6] Mark Wigley, Netzwerk – Fieber, in: Derive, Magazin der Interdisziplinären Wochen an der Muthesius-Hochschule für Kunst und Gestaltung Kiel, p. 4-35.

[7] See further: concordia.ca.

[8] See further: getty.edu.

[9] Piotr Rypson, Mail Art in Poland, in: Mail Art – Osteuropa im internationalen Netzwerk, ed. by Kornelia von Berswordt-Wallrabe, Guy Schraenen, Kornelia Röder, Staatliches Museum Schwerin, Berlin 1996, p. 87-93.

[10] Köszönöm az Artpool Művészetkutató Központban dolgozó magyar kollégiáimnak az ebben a szövegben nyújtott.

[11] György Galántai 1989, in: Mail Art, ed. by Kornelia von Berswordt-Wallrabe 1996, quoted in: Artpool’s Faxzine, Join the Network, Networker Congress Artpool, Budapest 1992.

[12] György Galántai, Leaflet,1989, Mail Art Archive Schwerin.

[13] Galántai Fluxus. Lifeworks 1968-1993, ed. Artpool and Enciklopédia Kiadó, Budapest 1996, p. 252.

[14] See further: artpool.hu (Editor)

[15] See further: artpool.hu.

[16] See further: artpool.hu.

[17] Kornelia Röder, Zur Marcel Duchamp – Rezeption In Mittel – und Osteuropa im Kontext des Netzwerks der Mail Art: Ein Interview mit Serge Segay.

[18] Eugen Blume,Robert Rehfeld–Art Worker and Mail Artist, in: Mail Art 1996, ed. by Kornelia von Berswordt-Wallrabe, p. 114.

[19] See further: artpool.hu.

[20] György Galántai, 1989, ARTPOOL’S FAXZINE. JOIN THE NET-WORK, August 24, 25, 26, 1992.

[21] See further: galantai.hu (Editor)

[22] See further: rayjohnsonestate.com.

[23] Marcel Duchamp, Where do we go from here?, 1961,in:Marcel Duchamp. Die Schweriner Sammlung, ed. by Kornelia von Berswordt-Wallrabe, Ostfildern 2003, p. 283.

[24] Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1987, p. 72.