Ken Friedman: Notes on the History of the Alternative Press

Friedman, Ken: Notes on the History of the Alternative Press, in: Lightworks, No. 8-9, 1977 Winter, pp. 41-47.

When moveable type introduced "modern" printing to the Western world, all publishing was alternative publishing. Facts, ideas, and news travelled through court and countryside by word of mouth, "published" in the original sense, made public, divulged, proclaimed. Books were rare documents of received knowledge and revealed truth, accessible only to the few elite members of society who knew how to read. Even scholars rarely owned books - they attended lectures at the academy and university, the very word lecture deriving from the fact that masters and professors tutored the assembled scholars by reading aloud from books or notes.

The act of modern publication bore within it the seeds of revolution, that is, knowledge that could be transmitted without the intervention of church or state. Early printers were commonly accused of heresy and treason. In some places, printing itself was against the law, while in others, it was guarded and licensed by crown or clergy, and was as carefully controlled as the minting of money. Print represented power, the power of ideas, letters and the "teeth of the dragon" ready to spring to life armed and full of power when sown on fertile ground. At our far end of their revolution, it is hard to realize the fear with which rulers greeted publishing. They knew what we sometimes forget: that in print, ideas are carried, and in those ideas, the perspectives that can change lives, states and nations.

Until very recently in our history, printing and publishing were inherently small and usually local processes. Long before moveable type appeared in the West, printing from blocks existed and printer's guilds flourished. The bestsellers of the Middle Ages were the emblemata and gemalpoesie which combined image, word, and drama for the literate and illiterate alike. After the modern press came into being, bestsellers were books such as the Bible. But if the Bible, the works of Shakespeare, and books like Tom Paine's Common Sense were best-sellers, they were not the great hits of their time because one publisher and a series of press agents made them so. Rather, these were books genuinely loved and sought by the public: printed in one location and distributed nearby. Perhaps another few copies would trickle to other places where new editions would be set and printed, almost as many separate editions in print as locations the books might reach. The single edition produced and controlled by one firm in hundreds of thousands of copies is a relatively recent innovation, first visible only in the last century, and not overly common until recent years.

Ideas and information moved in slow patterns: An editor received a letter from a friend, published it, and started the idea of the "correspondent". Newspapers copied stories from each other, paper-to-paper, one-by-one, and the first roots of the syndicate and the wire service took shape. In many cases, the town printer, editor and publisher were the same person, and often the newspaper office was stationery store, bookstore and even town library.

With the advent of the electronic age, wire services and mass media broadcasting gave a uniform surface image to the transaction of news and information. While there is much less uniformity among major publishers and broadcasters than is visible on the surface, the flavor and tone of publishing and broadcasting is very similar from place to place. Style sells papers and increases one's share of media markets. "Successful" styles, therefore, dominate viewing and reading markets today. The book market is similarly managed by a few large, successful companies which basically control the lion's share of the vast mass market.

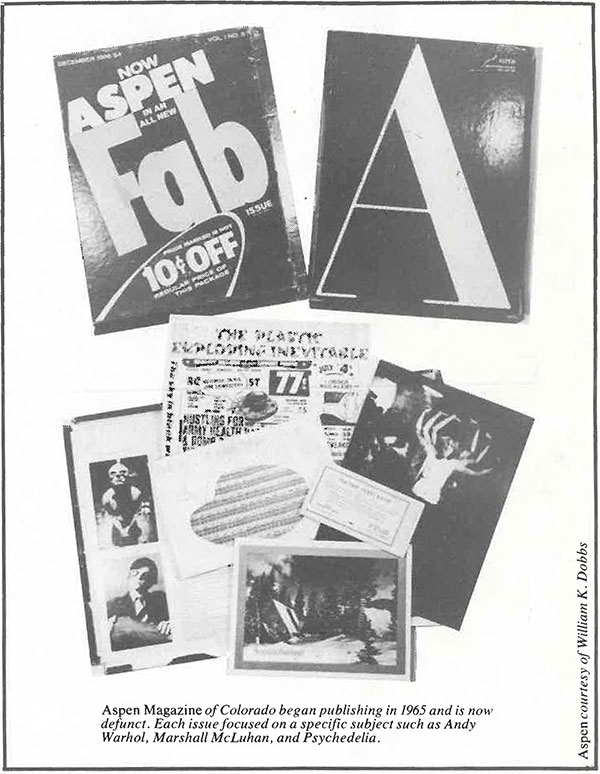

Aspen Magazine of Colorado began publishing in 1965 and is now defunct. Each issue focused on a specific subject such as Andy Warhol, Marshall McLuhan, and Psychedelia. Aspen courtesy of William K Dobbs.

While little magazines and literary journals have existed for hundreds of years, more recently, small political newspapers and related ventures, the first form of alternative publishing to have major impact on the American scene arrived with the Beat Movement and their authors and poets. When San Francisco's City Lights press published Howl by Allen Ginsburg, the first trickle became visible in what would ten years later become a flood tide.

IT WOULD BE AN exaggeration to trace everything to Howl, but as so many truths are exaggerations of their own fact, the history of interaction between art, literature and alternate publishing were typified in that work. That interaction, centered on the Beat movement, attended by wide controversy and wide public attention, foreshadowed the changes which were later to transform major sectors of public media in North America.[1]

Another focal point in this effort were the artists and composers in New York who had studied with John Cage at the New School and in his freewheeling, intermedial school of life. Many of them entertained new visions of what culture could be: denied access to established channels of public exposure, some of them began to create publishing networks of their own.

A major expression of those artists was the group known as Fluxus, an international group organized as a vehicle for publishing and performance in the early '60's. Fluxus approached the idea of publishing in the original sense: "making public and proclaiming", which naturally led to the creation of alternate spaces, films, festivals, and many other forms of public activity which have all been linked at one time or another with the alternate press.

John Cage and Fluxus provided the launch site for what was to become the largest and most far-reaching venture in the publication of artists' books ever to emerge: the Something Else Press. As a result of a short-lived feud between press founder, Dick Higgins, an artist and composer, and Fluxus editor, George Maciunas, Higgins established the Something Else Press in 1963. Heralded in the "Something Else Manifesto", the Press promised to "chase down an art that clucks and fills our guts."

Modern Correspondence by Tom Hosier. Contact P.O. Box 253, Plymouth, Connecticut 06782

Dadazine and Quoz of San Francisco. Contact: Bill Gaglione, 1183 Church Street, San Francisco, California 94114

The philosophy of Something Else Press was expressed in more rational terms in the opening passage of The Arts of the New Mentality, the 1967- 68 catalog of the press. In it, Higgins wrote that we are living in a Golden Age of literature-literature which was going unpublished because of the stifling nature of the controlled media and book industries. By literature, Higgins meant that commerce in ideas which informs our culture, our arts, and sciences as well as literature in the sense of poetry and writing. He pointed out that it was necessary for the artist and the thinker to also become producers: If we would see new ideas and new books published, we must publish them ourselves.

The middle '60's were fertile years for alternative publishing. In Berkeley, a newspaper called the Berkeley Barb was established in 1963, followed a year or so later by the Los Angeles Free Press together launching what would become the Underground Press Syndicate. The "U.P.S." got its most vivid push-off through the work of New York artist Walter Bowart, founder, publisher, and first editor of the East Village Other, a newspaper born as an artwork, as a cityscape collage of news and ideas. In late 1966, Bowart and a few other editors of similar papers around the country decided to work together for mutual selfhelp. They arranged a meeting scheduled to coincide with the January 1967 "Human Be-In" in San Francisco, an affair sponsored by The San Francisco_ Oracle., another U .P.S. paper. This was the first of the "be-ins" and "love-ins" that crowded the middle and late '60's. A Time-Life reporter asked Bowart during a telephone interview what the new syndicate would be called. Walter, at a loss for words, looked out his window, saw a United Parcel Service truck roll by and answered, "Uh ... the U.P.S." When asked what the initials stood for, he quickly replied, "The Underground Press Syndicate." In that way, using a collage process, an artist invented a style and name for one of the most important new styles of publishing to mark the 1960's.

Before returning to the art world proper, a brief look at the U.P.S. will be of value. Seven presses were represented at the January 1976 meetings in San Francisco and Stinson Beach where the syndicate was founded. These·were the East Village Other, Berkeley Barb and Los Angeles Free Press previously cited; the Washington D.C. based Underground, a tabloid with a penchant for publishing concrete poetry and avant-garde art;Fifth Estate, a Detroit newspaper one step beyond the traditional "Fourth Estate"; The San Francisco Oracle, a visionary paper produced and edited by poets and artists engaged in psychedelic revolution and ecstatic process; and Fluxus West, a branch of the Fluxus movement linking contemporary art and socio-cultural consciousness-raising. What blossomed into the several hundred papers of the U.P.S. started there: A mixture of artists, poets, and other disestablishmentarians who wanted to have the right to express their own ideas in their own way, rather than be ignored or suffer media distortion. At one point in its tumultuous history, the Underground Press Syndicate numbered almost 400 members across North America and around the world. Even following its relatively swift disintegration as an organized body, the U.P.S. served as an inspiration to the many hundreds of underground and underground-influenced, community style newspapers which have blossomed since its time.

During the period just after this, many art world alternatives began to emerge. Along with Fluxus, which reached both fine arts and mass culture audiences and Something Else Press, which staked out the largest territory in theoretical and documentary publishing, specialized vehicles came to birth. Of particular note was the Letter Edged in Black Press, organized by artist William Copley. The press published multiple magazines, containing not only neatly prepared trick inserts and foldouts, but actual signed works by artists whose names are now household words. The Letter Edged in Black publications are considered to be the inspiration for Aspen magazine, a publication which also derived ideas and works from the artists of Fluxus and of the Something Else Press.

THE MID-'60's also saw the birth of what was then an alternate publication, Artforum, in Los Angeles. The success of Artforum and the influence it has had on the art world demonstrates that what may begin as a radical venture can become so successful, and so alter the territory it seeks to change that it itself becomes the established medium, calling forth new alternatives in response to its own strength and power.

The mid-'60's saw the appearance of many important magazines. In 1966, Composer/Performer Editions of Sacramento, California, created Source magazine, a lavish 11 "x 14" journal which included special effects and records as regular features. Source featured work by new musicians and by artist/composer/performers crossing all media and style boundaries of the period. Issues included major new scores and photodocumentations of performances as well as philosophical texts by a regular Who's Who of contemporary composers ranging from Pauline Oliveros and Jim Tenney, to Phil Glass and Nicholas Slonimsky. Several issues were organized by guest editors, including John Cage, Ken Friedman, and Alvin Lucier.

That same period in history saw the genesis of contributor-edited magazines and anthologies. In 1968 and 1969, Amazing Facts magazine was born in California on a collation principle, and Omnibus News was developed in Germany on the basis of contributors sending in their own pages in multiple form. This latter format proved extraordinarily durable, and was used with great success by Ace Space Company in Canada for the Space Atlas journals, and by New York's Assembling Press for Assembling. While most of these titles no longer appear, Assembling continues to flourish under the guidance of Richard Kostelanetz, Henry Korn and Michael Metz with a Seventh Assembling to appear this year. Assembling by virtue of its wide distribution and visibility has influenced countless numbers of similar ventures ranging from local art school products to international gazettes such as Orgon and Ovum from Latin America.

By the late '60's artist-run presses and artist's books began to flourish, a field of such magnitude that a special article could be devoted to this topic alone.[2] Canada was particularly rich in artist-established presses, including Image Bank, General Idea, Coach House Press, Fanzini, Intermedia Press, Talon Books, and many more which were active by the early '70's. Many of the Canadian presses published magazines and special format releases such as postcards. For some time in the early '70's, Canada served as a world center for alternate press work by and for artists. Many of these presses operated conjointly with alternate space and exhibition programs, now an area highly developed through the Canadian Association of Non-profit Artists' Centers (CANPAC) which stretches down the Trans-Canada Highway from Victoria to Halifax, pumping ideas through the Canadian provinces like oil circulating through a finely tuned engine. As this process began to take place, Something Else Press was losing its energy and preparing to end its long run of production and creativity. Canada began to fill the vacuum, serving as a powerhouse and beacon in helping to promote and develop what the Canadians called "Eternal Network" consciousness around the world. The list of Canadian leaders includes now-major art-world figures such as Michael Morris, Mr. Peanut, Clive Robertson and the honorary Canadian, Robert Filliou, as well as cult heroes such as A.A. Bronson, John Jack Baylin, and the well-loved Ed Varney of the anonymous Poem Company.

EUROPE WAS NOT dormant at this time. Germany had long been a center of artist-publishers, very notably Hansjorg Mayer in the experimental contemporary art vein, and artists like Dietrich Albrecht in the proletarian position. In a special position of his own is German artist Joseph Beuys, whose activities have spawned hundreds of books, multiples, objects, chronicles, publications, commentaria and catalogs. Similarly, Beuys' friend and colleague, Klaus Staeck, is an artist and publisher who holds a unique position in German radical political art. In Germany, as in Canada, and as with the internationalist Americans, the same publishers were able to produce books, newspapers, postcards, and multiples under one press or aegis.

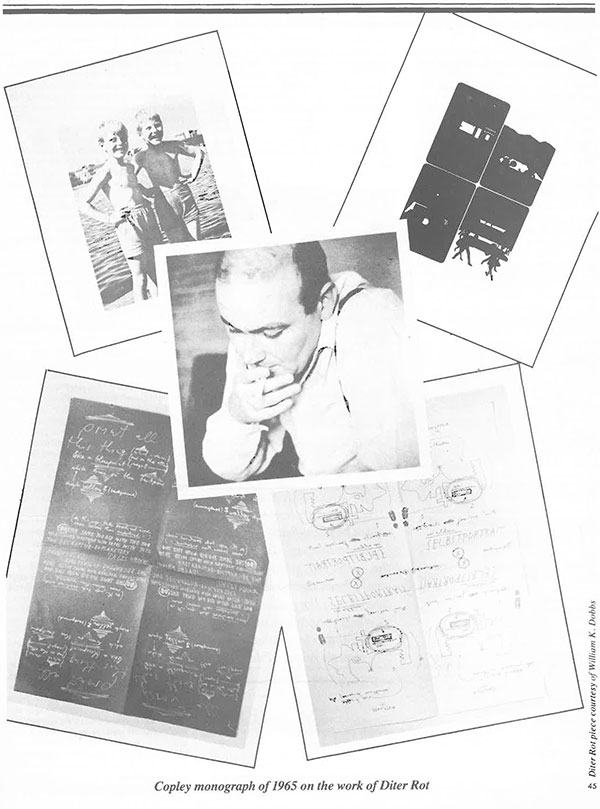

Copley monograph of 1965 on the work of Diter Rot

Of legendary stature as an artist-publisher is the famed IcelandicSwiss-German innovator, Dieter Roth. Dieter Roth (who has also been known as Diter Rot and Diter Roth, as well as Karl Deitrich Roth) has without doubt designed and printed more artists' books than any other major living artist. In hundreds of editions, large and small, by every printing technique known, many of which he himself invented, Roth has over the last 20 years poured out a neverending stream of books and printed artifacts. Once a very successful designer, Roth is considered one of Europe's leading artists. Edition Hansjorg Mayer began several years ago to publish Roth's Collected Works, so far totalling some 20 volumes, many combining several works into one. Forty more volumes are currently planned to make available the reprinted versions of original works by this prophet of artists' books movement. It is rumored that by the time the full 60 volumes are in print, Dieter will have finished 60 volumes more of original books and projects which will then need to be reprinted to keep up with the demand. As a typographer, designer, artist, printer, innovator and publisher, Roth has become the single most prolific and influential artist engaged in publishing the artist's book, and while essentially only publishing his own work, has done as much to influence artists' P.ublications as Dick Higgins and Hansjorg Mayer have done by publishing the work of other artists. Along with Roth, Higgins and Mayer, it is also necessary to mention WolfVostell, the German Happener and Fluxus artist, George Maciunas. They are considered by Europeans, Canadians and knowledgeable Americans to be as important to the present generation as the typographer-printers of the Dada and Bauhaus movements were to the past.[3]

Italy since the late 1960's has much resembled Germany, with the presence of Flashart, Arc Do, Ed 912, Multipla, Tau/Ma, Data, Aaa, and many others. Both Italy and Germany have benefitted visibly from the heritage and traditions of Futurism, Dadism and the Bauhaus.

In England, the role of architecture in artists' publishing has been larger than on the Continent or in the Americas. Architects and artists often worked together on little magazines and many magazines also were related to concrete and visual poetry. Magazines such as Arcade, Kontexts, Stereo Headphones and many more have won world-wide followings.

In 1970, the formation of a Fluxus West centre in England spawned the Fluxshoe, a process exhibition and series of performance festivals which toured Great Britain in 1972 and 1973. Also growing out of the process was Beau Geste Press, a publishing house which became a beacon for artists' presses in the mid-'70's. In the tradition of Beau Geste, now defunct, have emerged Ecart Publications of Switzerland, and Edition After Hand of Denmark. One of the special features of these presses has been the physical production of the books themselves: Rather than contracting their titles out, these publishers have acquired small offset presses and handled every aspect of their own production. In Beau Geste's Schmuck magazine and in the Ecart publications, multiple press runs, colors, overlays, and special effects have produced some of the most handsome and elegant artists' periodical's and books available. Many of these materials are available through Other Books and So of Amsterdam, which distributes the remaining Beau Geste stock and is one of the world's best bookstores for direct purchase and mail order of artists' books.

Artists' books and book distribution are now well-presented around the world, in this country through the Franklin Furnace, Printed Matter and other centers. The most recent issue of Dumb Ox magazine is devoted to the phenomenon of artists' books, and includes lists of places where one may acquire and see them.

File Magazine always poses form before content in

an art-as-life context. Contact: Art Metropole,

241 Yonge Street. Toronto. CANADA M5B1N8.

While artists had been involved in periodicals for some time, in the periods prior to the early '70's, they had generally been contributors and advisors, collaterally involved with production, editing and publication rather than directly responsible. The new movement in artists' periodicals saw artists taking direct responsibility, willing to spend the effort and energy, the disciplined work required for regular, serial publication as opposed to the much easier effort of a book product in a single or even small press context.

THE FIRST widely-visible artists' periodicals were not actually very widely released. They stemmed from the work of the New York Correspondent School and the availability of rapid offset printing. Ray Johnson's collages and printouts inspired a number of little ventures without names and then Stu Horn's image newsletter from New Jersey, The Northwest Mounted Valise. In 1971, the first small-format regular serial of this type of artist and art work was created, The New York Correspondence School Weekly Breeder. Rapidly followed by the many titles and magazines of the "Bay Area Dada" group of San Francisco, the phenomenon known as the "dadazine" was born.

There are now literally hundreds of Dadazines. Some are currently in print, others-such as the influential original Weekly Breeder and the renowned Quoz? are now defunct. Some of the titles still active are Modern Correspondence, Cabaret Voltaire, Or, Sluj and Luna Bisonte.

The "zine scene", as the phenomenon is known, produced a highline offshoot in the luscious magazines produced by groups such as General Idea. File Magazine is the classic example of lifestyle consciousness literature in an art-as-life vein. Parodying File is Vile, an item produced in the San Francisco Bay Area by another Canadian transplant group, Banana Productions, whose owner Anna Banana, also works with the Dadaland group of artists, poets and publishers. Very far out on the lifestyle angle are the personalist narratives or imagistic productions such as Fanzini and Egozine.

The second kind of artists' periodicals are the actual journals and newsletters. On the newsletter side are publications ranging from very small and informative bulletins such as the l.A.C. Newsletter published in Germany by Klaus Groh for the International Artists' Cooperative to the irregular trade exchanges of Spain' sLas Honduras. Moving toward information access in images and ideas, we find the Dutch Fandangos or the Polish Wspolczesna gallery newsletter. In America, of course, there are Diana Zlotnick's Newsletter on the Arts, The Original Art Report from the Midwest and others.

THE LARGEST AND MOST successful publication founded by an artist as an alternative publication in North America is Cecile McCann's Artweek . With strong international circulation, Artweek regularly provides a balanced coverage of the Western states and provinces, often with other news and in-depth essays. In a similar style is the very successful and popular Chicago-based journal, The New Art Examiner.

The mid-'70's have seen the appearance of a number of large journals. La Mamelle of San Francisco, founded in 1975 by Carl Loeffler, is published by an art information support network which began as a magazine, and which now includes a museum, gallery center, an archive, video and radio production and broadcast programs and facilities. 1975 also saw the foundations of another major new journal, the first in the South of its type, Contemporary Arts/Southeast. Founded by artists Tommy Mew and Ken Friedman, the first issue appeared in 1977 preceded by two years of development and work under a non-profit corporation headed by gallery director David Heath and librarian and artist Julie Fenton.

Dumb Ox of Los Angeles has recently moved from tabloid publication to journal form. The LAICA Journal is published under changing editors by the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art. Lightworks is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, devoted to the exploration of culture and art through photosensitive media. CrissCross Communications of Boulder, Colorado, has slowly been struggling toward financial stability, presenting the art and artists of the Rocky Mountain region in one of the bestdesigned periodicals now in print, after several improvements in style and format.

A number of publishers of the new journals are now banding together into a network known as Associated Arts Publishers, planning to work together to solve mutual problems to help each other to survive, providing service and information to their many constituencies. Conceived as an organization for alternative publishers, and founded by community activist and La Mamelle publisher, Carl Loeffler, the AAP is being guided by a board which includes Dadaland's Bill Gaglione, Ecart's John Armleader, Judith Hoffberg of the Art Librarians Society of North America, Michael Gibbs of Kontexts, Anna Banana of Banana Productions, well-known critic and champion of artists' books, Peter Frank, Stephen Moore of The Union Gallery of San Jose State University, Trudi Richards of La Mame/le, Lynn Hershman of The Floating Museum, and Ken Friedman of The Institute for Advance Studies in Contemporary Art and Harley Lond of Intermedia magazine. By drawing on the experience and expertise of members from all areas of alternative presses, Associated Arts Publishers hopes to forge a strong international community of concern and interaction.

Contemporary Art/Southeast

a bi-monthly journal.

34 Lombardy Way, N.E., Atlanta, Georgia 30309

The concept and practice of the alternate press is now so rich and so varied that even in an article such as this, every sentence omits a major title. If there had been room to look back in the century, magazines such as 291, Rong, Rong , Blind Man, VVV, and others would have cropped up. The discerning reader will note absences such as Spain's Centro Di and King Kong; Sweden's Vargen and Grisalda; and North American publications such as TRA, Praxis, Art-Rite, Ear, The New Wilderness Newsletter, and many more. Honored names in the alternative press such as David Mayer, Beth Anderson, Maurizio Nannucci, Mario Oiaconno, and alternative press supporter/archivists such as Jean Brown and Hanns Sohm have not been presented or discussed. No room has been given to the great alternate press collections and centers such as Archive for New Poetry at University of California at San Diego, Germany's Archiv Sohm, the Tyringham Institute in Massachusetts or the Library of the National Collection of Fine Arts at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

This article is a brief survey: It identifies the intellectual and aesthetic currents at work in our culture today without recognizing every contributing force and unfortunately perhaps leaving some out in favor of others.

Through publishing alternatives, artists, critics and art historians take the production and distribution of thought into their own hands, creating senses of community and intellectual exchange which are necessary to a diffuse and growing spirit. What we lose in uniform sensibility and homogenous vision, we gain in the sense of self, place and position. What is to be hoped is that just as literacy spread with the advent of the printed media in the first publishing revolution, so an ability to deal justly with ideas and to conduct well-tempered discourse will emerge as we each have the opportunity to direct the nature of our discourse through the control of our own presses and magazines.

________________________

[1] For deeper historical information on this topic, Howardena Pindell's history of artists' periodicals in the Fall, 1977 issue of Print Collector's Newsletter goes back as far as 1900. This article, basically covering the period since the Second World War is naturally more limited in scope

[2] Judith Hoffberg and Joan Hugo are preparing to organize and tour the definitive exhibition of artists' books through the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art in 1978. This exhibition will hopefully be accompanied by a catalog in which Hoffberg and Hugo, two of the great authorities on artists' books will clarify and present the many histories of this fascinating medium.

[3] Despite the fact that there are over 3,000 accredited institutions in North America in which one may study art and art history, decent scholarship and research in contemporary art movements or art since 1945 is very rarely seen. The reasons for this situation are many, some reasons good, but the situation does exist.