Edgardo-Antonio Vigo: The State of Mail Art in South America

Vigo, Edgardo-Antonio: The State of Mail Art in South America, in: Correspondence Art. Source Book for Network of International Postal Art Activity, Contemporary Art Press, San Francisco, 1984, pp. 349–367. (Ed. by Michael Crane – Mary Stofflet)

Let us try to put together some facts about mail art—its theoreticians and practitioners, what has been done, and the possibilities for the future. We don’t recognize any “founders” who consider themselves thus simply for using the mail to send works of art, since the mail is a universal means of communication. Let us make it clear that mail art does not consist of mailing literary or fine works of art to an exhibition, nor does it consist of mailing invitational postcards even though these may have some artistic purpose or aesthetic design. If we were to accept such a thesis, we would find ourselves face to face with a pile of predecessors that would be truly monstrous in size. We can, of course, justifiably give these activities the well-earned description of “those who opened up or created the possibility of a communicational-creative activity.” They are generative. Thus the greeting cards, the holiday wishes, the correspondence between artists. Horacio Zabala and Edgardo-Antonio Vigo gave a definition in their article, “Mailart: A New Form of Expression,” part of which follows:

A distinction must be made to clarify the concept. When a sculpture is sent by mail, the creator limits himself to using a specific means of transport to move an already completed work. While the sculpture was coming into being, this removal was not taken into consideration. In contrast, in the new artistic language we are analyzing, the fact is that a work must cover a particular distance as part of its structure, it is the work itself. The work has been created to be sent by mail, and this factor conditions its creation (dimensions, postage, weight, nature of the message). Thus the purpose of the mail is not simply to move the work but to condition it and form an integral part of it. And the artist, for his part, changes the purpose of this means of communication. There also occurs a modification in the attitude of the recipient; he is no longer the classic collector (a condition which implies a kind of egoism) but an accidental depository of the work, who is obliged to give it maximum circulation. The recipient is a source of information that opens a new circuit of communication when he enriches the work by exhibiting it or mailing it to new recipients.[1]

In support of the above, Walter Zanini, director of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Sao Paulo (Brazil), in reference to the practice of mail art, says:

Mail art belongs to a class of systems that breaks down barriers separating the levels of art from those of life. The motivations for this new expression are multiple and do not depend on any one particular circumstance. Artists, in considerable numbers, are breaking away from the traditional concept of “work”; they are moving away from official and commercial shows, and are mistrustful of the function of criticism and indifferent to the dominant art magazines—that is they are hostile to all the status mechanisms that would seem indispensable to an artistic career. They are organizing instead to present a different situation, creating their own exchanges, their own publications and selecting their own locations for expositions. They are becoming economically independent of the centralizing mechanisms of art, dedicating themselves to parallel activities. Communication through postal correspondence will become an important element for the conciliation and expansion of this autonomous behavior. No one can doubt the great incentive that is signified by mail art, especially for the younger generation. It means a step forward in the direction of a democratization of activities, in the direction of an effective questioning of bureaucratic demands, and it may be—if it doesn’t get bureaucratized itself—an always growing contributing factor in the formation of a new culture.[2]

Edgardo-Antonio Vigo and Horacio Zabala, Last International Exhibition of Mail Art, Argentina, 1975. Cover of the exhibition catalog.

G.E. Marx Vigo (top), First Day Cover, Argentina, 1978. Postcard with rubber stamps. Leonhard Frank Duch (middle and bottom), untitled, Brazil. n.d. Rubber stamps.

Jonier Marin, a Colombian artist, using the mail as a medium, printed in February, 1977 a communication entitled On Mail Art (Bogota, Columbia) from which we choose the following words: “Artistic work has become an isolated, a marginal, phenomenon. Mail art guarantees an intimate contact with the addresses, overcoming the distance of the usual exhibition, placing the artistic message in the middle of ordinary correspondence between friends, family members, or places of business.”

There is no doubt that Clémente Padín, fomentor and participant in the events of mail art, is one of the most interesting theoreticians from this southern part of the Americas. In any survey of the field his work must be represented:

Art frequently gets revenge on the cultural entropy generated by officialized art and by those wornout artistic forms that hold up the established systems in order to reaffirm things already known or “already given in art,” by changing the function of the means of communication either by transforming the information (content) or by taking advantage of the properties of the medium for the transmission of its own messages—such is the case with postcards which have been converted from a commercial object into one of today’s principal means of artistic diffusion thanks to the speed and extent of its dissemination anywhere, to the simplicity of its manufacture, storage and consumption, and, especially, to its innumerable expressive possibilities as a simple support for verbal, iconographical or other communications or as an artistic object in itself, creating its own language.[3]

In 1969, for one of the annual happenings (experiencias) presented by the Instituto Di Telia (Buenos Aires, Argentina), artists Liliana Porter and Luis Camnitzer developed, by means of the mail, an experience that fits perfectly within the theories about mail art. Through four mailings, they sent envelopes containing an enigmatic proposition to persons on the Institute’s address list. Later, on the day of the event, the questions were answered in the reality of the works, based directly on the cards whose facsimiles had been mailed out. The intentions of the artists are unknown—perhaps they were responding to the characteristics of the gallery’s happenings—but we can’t avoid wondering to what extent the director of the Institute, Jorge Romero Brest, modified ideas from the original work of the artists, knowing as we do his method of working. To better illustrate this event, let us transcribe the texts proposed by the cards:

LILIANA PORTER

Contents: Exhibit no. 1—text: SHADOW FOR TWO OLIVES

Contents: Exhibit no. 2—text: SHADOW FOR A BUS TICKET

Contents: Exhibit no. 3—text: SHADOW FOR A GLASS

Contents: Exhibit no. 4—text: SHADOW FOR A TURNED CORNER

LUIS CAMNITZER

Contents: Exhibit no. 1—text: FOR USE AS A MIRROR AND TO BOW THE HEAD

Contents: Exhibit no. 2—text: TO STOP SINGING AND TO CRUSH AS AN EXERCISE IN POWER

Contents: Exhibit no. 3—text: TO CHROME, SHARPEN AND CUT MEDALS

Contents: Exhibit no. 4—text: TO CUT OUT IN THE FORM OF A SWASTIKA AND TO USE AS A NATION OF CONCENTRATION

In addition, starting approximately in 1967, the intense activity of the Grupo Diagonal Zero, initiator of the current experimental visual poetry in Argentina, has been undergoing changes in the direction of mail art. Carlos Raul Ginzburg and Edgardo-Antonio Vigo, from La Plata, are both initiators of postal activity: their work has matured and become true postal communication. The recipient is invited to participate in group, individual, political, or entertainment activities. Ginzburg made a series of envelopes where the writing appeared on the outside: the insides (before sealing) lack contents. Later he developed, for specific dates, mailings based on elements that were in agreement with what the dates signified (for example: on the first day of Spring, September 21, he sent out flower seeds). Vigo created actions—going, returning, going again—in a sequence which, if followed to an extreme, would annihilate all movement (for example, “[In] conference” 1969).

The Centro de Arte y Comunicacion de Buenos Aires (Argentina) — CAYC — directed by Jorge Glusberg, has a system for distributing brochures by mail. The brochures, 750 by now, contain a real history of contemporary experimental art, as well as important theories, tendencies, and information. Around January 1974, CAYC published a series (unfortunately published no longer) called CAYC Postcards (Las Postales del CAYC). The six that were printed were generally related to conceptualist theories. A text on the back explains the author and his work. The authors were from the Group of Thirteen (Grupo de los Trece). Their names are mentioned here according to the numerical order of the cards: 1. Luis Paxos, 2. Edgardo-Antonio Vigo, 3. Victor Grippo, Jorge Gamarra, 4. Jorge Gonzalez Mir, 5. Alberto Pellegrino, 6. Juan Carlos Romero.

The first South American mail art exhibition was in Montevideo (Uruguay). It was organized by Clémente Padín under the title Festival de la Postal Creativa, in the Galeria U, and ran from October 11 to 24,1974. Although it contained only one branch of mail art, the postcard, it was an enormous exhibition, almost exhaustive, where all the possible permutations of the postcard could be found. The reading of the exhibition presented a new phenomenon, since the cards, which were tied to the ceiling, hung down. The spectator, in addition to touching the work without impediment, could, if he dared, carry away a souvenir. We insist on the term “reading” of the exhibition, because we believe that herein lies a fundamental element of the language of this art. Perception of the work requires a different time; if visual poetry, graphics, and fine arts affect the spectator with their images in “different times,” mail art also requires a “different time,” in addition to a different intellectual content. It further requires current sociopolitical information, since the possession of such data creates a greater comprehension of the work, without forgetting, of course, those artists who are concerned with the aesthetic level as well.

Brazil is not absent from this avant-garde. It was in the city of San Pablo where Ismael Assumpção organized the Primeira Internacional de Correspondencia, which ran from the 7th to the 15th of September, 1975 in the Colegio Duque de Caixas. The exhibition was limited to a few internationally known artists who were in contact with the organizer. Nevertheless, on the list of participants there appeared some names fundamental for the later development of mail art in the countries of South America. Assumpção defines mail art in this way: “This art is not closed, nor is it a system; it is an open art, incomplete, subject to constant revision.” His words hold great enthusiasm and faith in future developments.

Horacio Zabala and Edgardo-Antonio Vigo were the co-organizers of the Última Exposición International de Artecorreo, which took place December 5, 1975, in the Galeria Arte Nuevo, Buenos Aires (Argentina). Organization took the whole year of 1975. There were twenty-four countries represented and 199 participants. All means of communication were used and the exhibition received extensive publicity. The result was rather meagre; the fact that the exhibition took place in an “unsuitable” place—an art gallery—reduced the impact on the forewarned artists and public who questioned its validity from various personal points of view. There was even the problem that in the Argentine section, the director of the gallery forced the inclusion of artists who had never before or since participated in an exhibition of that sort.

Once again Brazil comes into view with the exhibition organized by Paulo Bruscky and Leonhard Frank Duch called Primeira ExposiçãoInternational de Arte Postal, which ran from December 1975 to January 15, 1976. Due to one of those accidents that always divides the different periods of art, the location of the exhibition was not in the usual museum, gallery, or art center. We wish to reemphasize here that presentation in a public space where the spectators are not expecting it produces the “aesthetics of surprise.” Thus for the first time in South America, a proper place for the new expression was found; that is a new environment. This show was not, perhaps, definitive, but its value lies in this opening. Here are the comments of one of the organizers, Leonhard Frank Duch, in a letter to Vigo dated January 22, 1976: “The exposition was based on the idea of putting together all the material received from the many friends of mail art, although there wasn’t a great deal. We wanted to have the show at the Post Office, but we couldn’t get permission. So we put it up in a large room of the Hospital Barao de Lucena, a government hospital. There was an enormous table with a glass top and we put the work beneath the glass.”

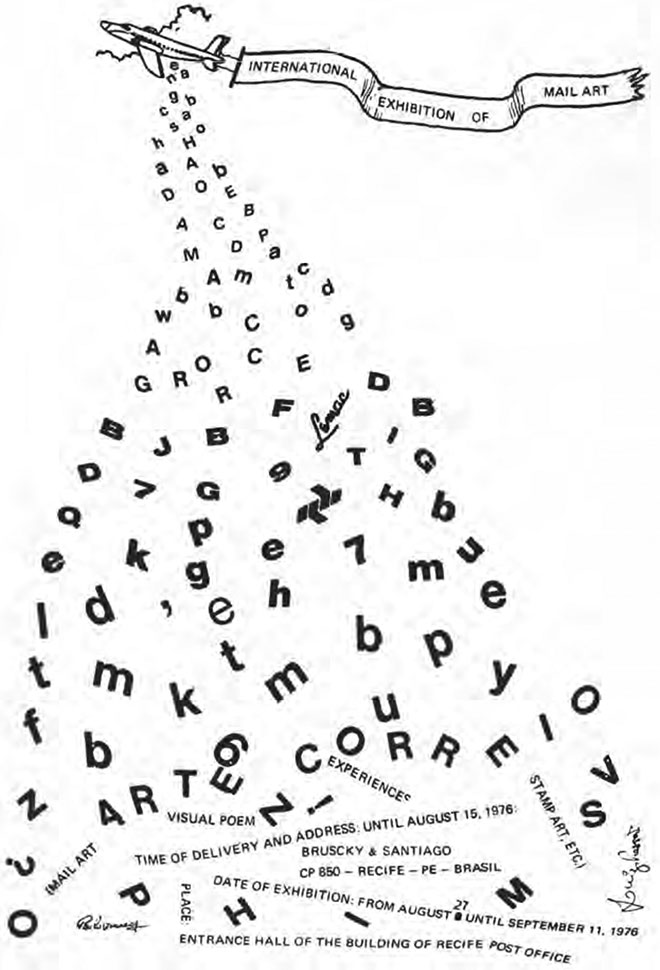

To conclude this review of the exhibitions organized up to now in South America, we must discuss the International Exhibition of Mail Art, which was organized by Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago in Recife, Brazil. It was to run from August 27 to September 11, 1976. Those of us who were not present were surprised to receive a circular in which the participants and critics were notified that “The exposition ... was suspended for reasons beyond our control.” Those reasons were revealed later. It was, quite simply, the beginning of censorship. Mail art had had its first confrontation. In a letter of March 2,1977 Paulo Bruscky explained what happened to the author of this article: “You probably already know that the Segunda ExposiçãoInternational de Arte Correa was prohibited and censored by the police and that we (the organizers) were even held prisoner for three days. The exposition was closed one hour after its opening.” Bruscky, in a letter of March 3,1977 denounces the fact that the works seized by the police were returned one month later, torn up and partially destroyed. This included works not only by Brazilians but by foreigners as well, and many of them are irretrievable because they form part of the police processes. A sad fate for a youthful expression. Unfortunately, such occurrences are spreading.

Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago, International Exhibition of Mail Art, Brazil, 1976

Finally, to sum up, we will list the practitioners of mail art by country. The selection has been based on the quality as well as the quantity of the work.

Argentina: Carlos Raúl Ginzburg, Juan Carlos Romero, Edgardo-Antonio Vigo, Horacio Zabala, Graciela Gutiérrez Marx, Luis Iurcovich, Luis Catriel, Reni Levy and occasionally some members of the Grupo de los Trece (CAYC).

Brazil: Unhandeijara Lisboa, Paulo Bruscky, Ismael Assumpção, Gastão de Magalhães, Luis M. Andrade, Samaral, Leonhard Frank Duch, Odair Magalhães.

Chile: Guillermo Deisler (currently in exile in Bulgaria).

Colombia: Jonier Marín.

Uruguay: Haroldo González, Jorge Caraballo, Clémente Padín.

Venezuela: Diego Barboza, Dámaso Ogaz, Luis García, Óscar Sjöstrand, Villasmil, Luis Viyamiser.

Translated from Spanish by John M. Bennett, Luna Bisonte Prods.

________________________

[1] Horacio Zabala and Edgardo-Antonio Vigo, “Mailart: A New Form of Expression,” Postas Argentina!, no. 370, October, 1975.

[2] Walter Zanini, “Mail Art in Search of a New International Communication,” O Estado de Sao Paulo, March 27, 1977.

[3] Clémente Padín, Festival de la Postal Creativa, Galeria U, Montevideo, Uruguay, 1974.