Joachim Frank: The Expanding Network: Toward the Global Village

in: Eternal Network. A Mail Art Anthology, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, 1995, pp. 112–116. (Ed. by Chuck Welch)

Networking in Science and Arts

My personal experiences with networking have been in the different realms of science and the arts. As a research scientist at the research laboratories of the New York State Department of Health, I work on three-dimensional visualization of structures at the molecular and cellular levels. As a writer, editor, and visual artist, I have contributed extensively to the artists’ networking publications, Prop and Artcomnet. In these seemingly different science and arts activities I experienced, besides the focus on visual themes, the aspect of networking as a common denominator.(1) In science, it is commonplace to find an international group of investigators, representing a multitude of fields, collaborating on the same project. In the arts, where traditionally individual authorship is more highly valued than a share in collaborative work, the phenomena of mail art(2) and correspondence art have created a new, legitimate platform for participation, and thus have brought science and arts onto a more equal footing.

Most interesting in the context of our topic, networking in science is exemplified in the process by which a manuscript with collaborative authorship is drafted. This process constitutes the most intense period of the collaboration. In principle, an infinite number of drafts is necessary for convergence of a consensus because each time a draft is changed by one participant the next one in the circle is confronted with a new context. This is similar to the process of tuning a piano, which has no exact solution, because the tuning of each string affects the tension of the strings already tuned, and consequently brings them out of tune again. In practice, the circle is broken by an exercise in restraint and by the abandonment of overly pedantic standards.

Before the onset of electronic mailing via computer networks, a manuscript used to physically travel over large distances, accumulating layers of comments and insertions. When on a sabbatical in England in 1987, I benefited for the first time from the computer network that links many academic institutions, and I was able to receive, edit, and send manuscripts across the world and receive a reply to my comments, all in the space of a single day! This experience had a profound effect not only on the efficiency of scientific collaborations, but also on the way I perceived myself in relation to the globe around me. This was, perhaps, similar to the experience of astronauts who for the first time see the planet Earth as a detached ball in the sky, and who have spoken about their sense of awe, despite the fact that they knew all along that this was going to be what Earth would look like. I believe that this perception of sitting in a “live node” that is connected to many points across the globe — and the feeling of simultaneity that comes with it — will have a profound effect on the artists and the art once they share the same ready access to the electronic network as is now available for scientific research.

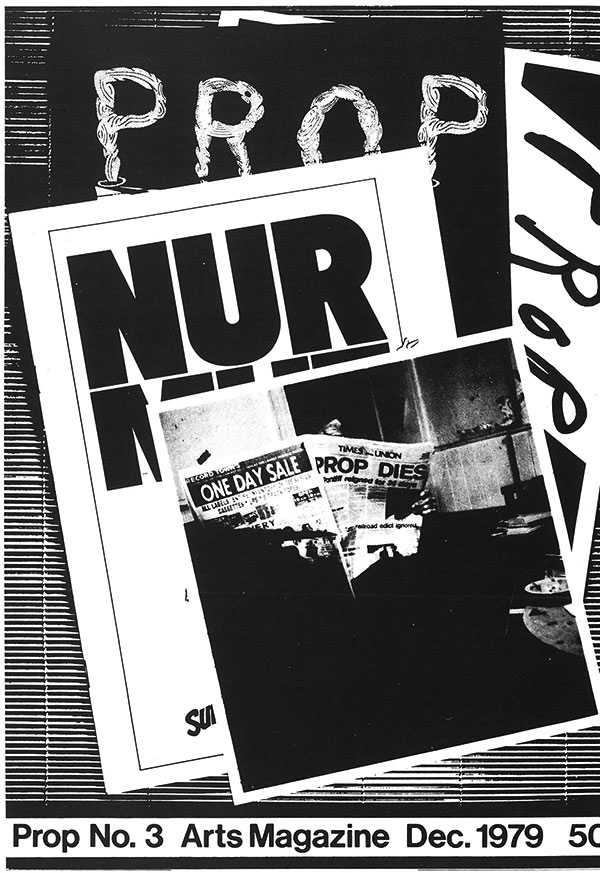

Figure 70. Joachim Frank: Prop cover, No. 3., Arts Magazine, December 1979

Figure 70. Joachim Frank: Prop cover, No. 3., Arts Magazine, December 1979

This brings me to my experiences from 1978 to 1986 as an editor of Prop(3). (Fig. 70) During that time my correspondence with the contributors was limited by the speed and success of physical transport of mail through the postal system. Prop was founded in Albany, New York by a group of artists known as Workspace(4) and became a new focus point for the group after a two-year uninterrupted series of performances. This origin of the magazine explains the immediate emphasis on projects that invited reader participation (e.g., the Void Show(5)). Prop was first edited on a rotating basis by two or three members of the group; in later issues I assumed a primary role by default. Prop first acted primarily as a documentation of collaborative visions and brainstorms of the group; later, when the magazine became widely circulated, it enjoyed some popularity among experimental authors and mail artists. At this stage, the volume of the correspondence with authors and readers became enormous — an indication that Prop, as similar magazines, was meeting a new need: artists needing an exchange of visions in a free form not supported by academic or descriptive journals. Not surprisingly, the days of the magazine were numbered when Workspace dissolved. Prop became the self-reflection of the single, remaining editor; a node without a network.

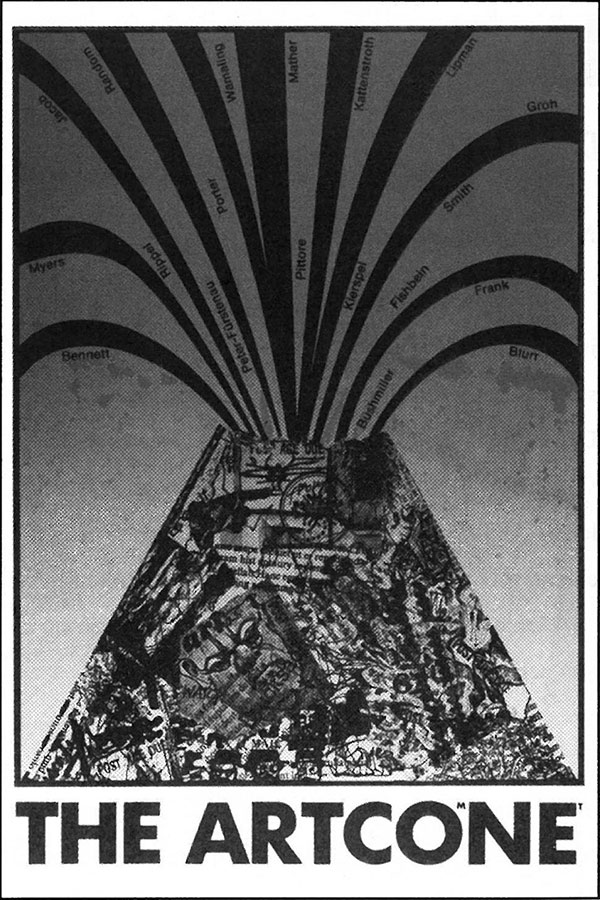

Figure 72. Joachim Frank, ARTCOMNET, U.S.A., 1984. Postcard

Figure 72. Joachim Frank, ARTCOMNET, U.S.A., 1984. Postcard

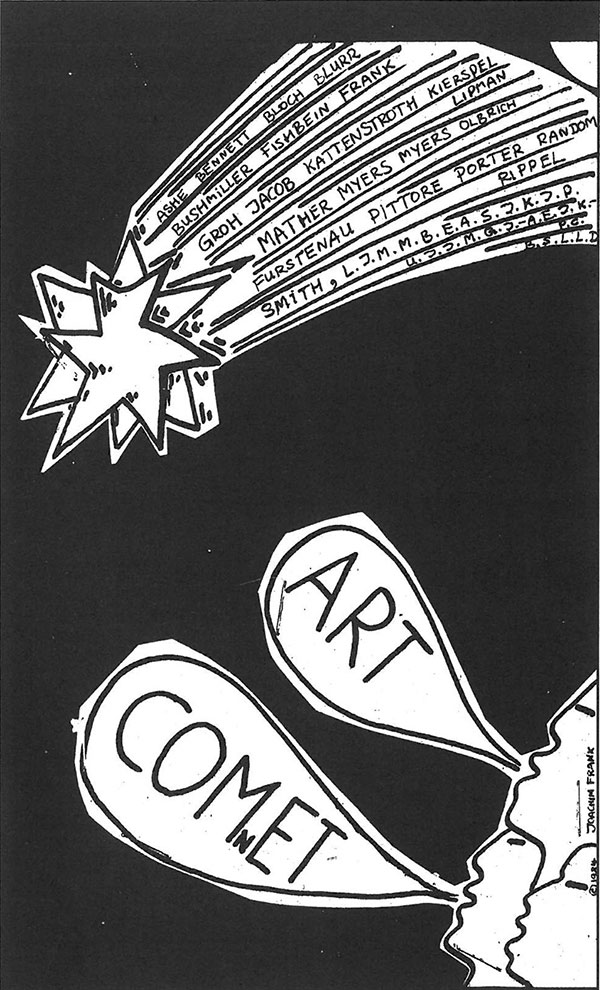

Figure 71. Joachim Frank, ARTCOMNET, U.S.A., 1984. Postcard

Figure 71. Joachim Frank, ARTCOMNET, U.S.A., 1984. Postcard

Another experience with networking comes from my participation in ARTCOMNET (ART COMmunication NETwork), a group activity centered around a xeroxed newsletter organized by Larry Smith(6) in 1982. For five years and 25 issues, Smith adhered to the principle of reproducing everything that was sent in by group participants: notes, announcements, letters, poems, visuals, etc.(7) We could have called him accumulator rather than editor, had it not been for a process of “editorial networking,” that is, addition of comments that tie all pieces together in some way. I think that this seemingly impossible mediation of the ARTCOMNET newsletter was both skillful and successful, and served as an unpretentious forum for ideas, monologues, and chats about the struggles of artists in search of their art.

The existence of ARTCOMNET helped establish distinct relationships among some of the participating artists, who started correspondences and interactions outside the framework of the newsletter. However, ARTCOMNET had no identity or direction as a group in terms of artistic or aesthetic concepts. In Smith’s words, “I decided to try to set up a situation in which unacquainted artists could communicate back and forth, allowing their thoughts to be shared openly and unrestricted by formality.”(8)

What I found particularly interesting were the attempts to create a mythology by means of works-that have the group itself as a theme: the Yearbook, from which Smith was quoted before, was an attempt at self-reflection and self-representation of a group that had no common goal other than interaction and exchange of creative ideas. Ironic references to a purported unity and great influence are also found in postcards created by various group members. These postcards feature themes that allude to power and fame: a volcano (Figures 71 and 72), MTV, and Halley Comet.

Brain Storm and Lone Ranger

It is intriguing to see how today’s world-wide electronic network is in some sense an embodiment of Robert Filliou’s 1965 visionary phrase “eternal network” at a time when computers were, in fact, still huge, solitary, disconnected boxes. Later, the terms “ethereal open network” and “neonic network” emerged in the correspondences between Chuck Welch, Vittore Baroni and Volker Hamann in their 1986- 87 international networking project, Netzine.(9) In part, these three mail artists were emphasizing the ethereal, delicate qualities the communication network was bestowed with, qualities not always of material, objective reality. Interestingly, there exists a fortuitous reference to “ethereal network” in the word, “ethernet,” the name of a present hardware connection that is frequently used to link computers together.

So far, scientists have been the main beneficiaries of the new age of instant worldwide communication; however, even though sponsorship of the arts and humanities is minuscule compared with that of science, it is not futuristic to think of a time when artists will gain wide access to electronic networks. To imagine what kind of impact this new means of communication might have on the arts, we should consider both of its components, the “medium” (form) and the “message” (content). Electronic networks are an example of a communication means where these aspects are clearly differentiable, the main message of Marshall McLuhan’s treatise notwithstanding.(10)

The message aspect lies in the fact that existing ideas can now travel much faster than before. The artists’ ability to interact thousands of times faster will accelerate the development and spread of artistic ideas, just as the onset of jet travel has accelerated the proliferation of new forms of the flu. In the same vein, we could think of the future when visual information might be transported with the same accuracy and speed, so that contents of messages may also be entirely non-verbal.

An interesting perspective arises when we consider the medium aspect and see the electronic network as an actual new field of artistic expression. The electronic network — when used as an immaterial extension of mail art — may permit the unfolding of artistic ideas into a new, global performance space: figuratively speaking, onto the plaza of the global village. Here is the site for the ecumenical art activism that Chuck Welch envisions in the Introduction to this anthology. By engaging thousands of minds in the pursuit of a concept, the artist would be able to initiate or orchestrate a communication-happening on a global scale. Networks might be the appropriate name, analogous to the tangible earth-works of the Sixties and Seventies(11). It is difficult to speculate what particular forms these happenings may take, except for two models that come to mind: the “Brainstorm” and the “Lone Ranger.” In the Brainstorm model, an idea, tossed out into the network, is being quickly illuminated from all possible directions. Such an event is self-documenting because all mail activity created in response to the original idea (along with all of its followups) winds up in everybody’s computer.

The Lone Ranger model of the communicationhappening would take advantage of the lack of authentication of electronic mail, which enables an artist to take on any desired identity: he is able to masquerade as a scientist, bureaucrat, politician, or plumber, and conduct conversations, issue requests or unruly ideas. In the process of this interaction, amazing insights are obtained, and thousands of minds are stimulated.

Conclusion

Whenever new territory was explored in the past, it also became a playground for human imagination, and thus, by implication, a space into which art could unfold. The electronic network constitutes a new space, but this space is unique in that it is spanned by nodes and connections, and that it facilitates instant global interaction. The concept of the global village arrived quite naturally: a village is the place where people are in shouting distance of one another, where people speak the same language, where gossip thrives, where people are held together by common fate. The networks have arrived just in time, it seems, to make the changes in global thinking manifest in the arts. If everything goes right, electronic net-works may become the plaza on which the street-theatre of the global village will take place.

(1) For more views on the subject read Joachim Frank’s “Networks and Networking,” The Works, September, 1989, III: 8, 13, 19.

(2) Some ideas about mail art are found in Joachim Frank, “On Mail Art and Mail Artists,” Umbrella, March 1984, VII: 2, 45.

(3) The subject and author index to all 13 issues of the magazine is found in Prop 13 (1986). Copies of the magazine can be located at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY and at the Centre de Pompidou, Paris, France.

(4) Workspace, an Albany, New York based group of performance artists, musicians, and painters, founded in 1976 to seek a noncommercial basis of art expression.

(5) Void Show, solicited in Prop #1, exhibit 1980 by Workspace Loft, Inc., Albany, New York. Listed in “Selected List of Mail Art Exhibitions” in Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet, eds., Correspondence Art, Contemporary Arts Press, San Francisco: 1984.

(6) Larry D. Smith, visual artist living in East Freedom, Pennsylvania. Major projects: The ShNn Report, a magazine coedited with Larry Rippel; Manifesto sHnnalchemy, 1981; Artcomnet Newsletter, 1981-1987.

(7) Larry D. Smith, “Once Upon a Time...”, in Klaus Peter- Furstenau, ed.. The Real McCoy, A Yearbook of Artcomnet, Frankfurt, 1986, 6-8.

(8) Larry D. Smith, Ibid.

(9) Vittore Baroni, Crackerjack Kid, and Volker Hamann, The Making of Netzine: A Collaborative Net-Working Tool for Discovering Ethereal Open Networks, Forte Dei Marmi: Near the Edge Editions, 1989.

(10) Marshal McLuhan, The Medium is the Message, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989.

(11) Susan Sontag notes, “What is primary in a Happening is materials — and their modulations as hard and soft, dirty and clean” (“Happenings: an art of radical juxtaposition” in Against Interpretation, New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1964). With matter as the main ingredient removed, the Communication Happening would only share the attributes of unpredictibility and unruliness with its predecessor.