Rea Nikonova: Mail Art in the THE U.S.S.R.

Nikonova, Rea: Mail Art in the THE U.S.S.R., in: Eternal Network. A Mail Art Anthology, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, 1995, pp. 95–99. (Ed. by Chuck Welch)

With glasnost, the Soviet nation removed Communism’s Little Red Riding Hood with a balletic gesture. Meanwhile, the military held theatrical meetings, chanting in unison about weak-minded leaders. Coming through the sewage hatchways, monarchists in full uniform sat confidently in broken, three- legged armchairs, sculpting, modeling their plasticine white horses to be ridden into the Kremlin. Russia, choking from the smoke of “roasted facts,” allowed foreigners to roam about the country with microphones; dissidents gave interviews, emigres published their books in Moscow and Soviet maestros left the country in droves.

The Soviet government’s most favored organization, the KGB, stood, face strained yet smiling, while it solemnly announced its willingness to shake the hand of every human killed or tortured on its account. With this announcement, a third of the KGB staff traveled abroad as representatives of dissident circles.

With these tumultuous beginnings of glasnost and perestroika, mail art began to emerge within Russia. The beginning of Soviet mail art can be traced to these political events, but in 1985, the international “Experimental Art Exhibition” in Budapest had an equally profound effect. That exhibition, sponsored October 21-November 21,1985 by the Young Artists Club of Budapest, mailed invitations that Serge Segay (my husband) and I accidentally received. Having entered the show, our mail artwork, names and address appeared in the Hungarian catalogue on pp. 165-166. Soon thereafter, the mail artists Ninad Bogdanovich (Yugoslavia), Daniel Mailet (New Caledony) and Harley Francis (USA) wrote to us.

From that time onward, Serge and I mailed thousands of original mail artworks each year, a time when Xeroxing copies was illegal and conviction often led to imprisonment.

Serge and I often sent our mail artworks to complete strangers, and in reply we received Xerox copies of participants in mail art shows. Amidst the in-coming mail, art of beauty and originality arrived daily and was included in the exhibition Mail Art: The Artists from 25 Countries which we organized January 1989 in Yeisk. This was the first mail art exhibition in the U.S.S.R. Prior to our Yeisk mail art show, I sent a few mail art bulletins about my project “Write Yourself.” The project drew seventeen participants from eleven countries. All these mailed artworks were included in the Yeisk mail art exhibition.

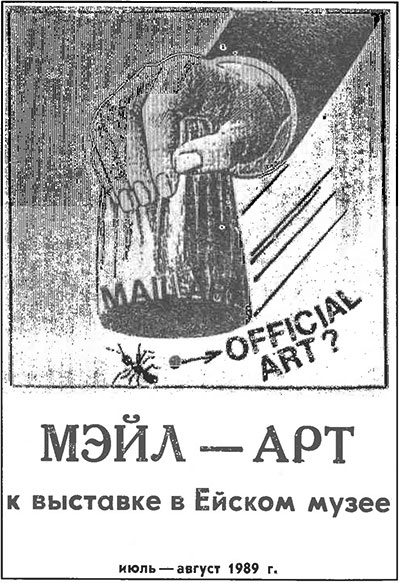

The Yeisk mail art exhibition included work by 105 artists from twenty-five countries (Fig. 60). Serge personally guarded the works and talked to the press. As for me, I played the role of show guide. With the help of the Yeisk Museum, a placard was printed for the exhibition, but the catalog had to be ordered privately, and then be “improved.” We mailed all the documentation with our personal funds, Yeisk Art School provided the space, and the Museum kindly agreed to finance most of the show. TV journalists from our regional center, Krasnodar, arrived at the show, interviewed Serge, and shot a video clip that was broadcast in Krasnodar.

All of this activity inspired me to create a new mail art project I entitled “Scare-Crow.” I advertised “Scare-Crow” in many bulletins and mail art notices and responses came from ninety-five participants living in twenty-three countries. The exhibition took place in the summer of 1989. Afterwards. I mailed a placard and several photos of the exposition to all of the participants. Due to the peculiarity of our postal service, Serge and I had to mail the documentation package as often as three times to some participants. We also involved third parties to assure delivery.

Figure 60. Serge Segay, Mail Art: The Artists from 25 Countries,

Russia, 1989. The bold blockprint exhibition poster announces

the former Soviet Union’s first international Mail Art exhibition.

Presented at the Yeisk Art School in January 1989, Serge Segay

and his wife Rea Nikonova organized the show, which proved

to be a catalyst for Mail Art activity in the Soviet Union.

We sent the mail art exhibition Mail Art The Artists from 25 Countries traveling around the U.S.S.R., and to the Urals (Sverdlovsk), where it was such a success that a mail art club was created there. Further travels of the exhibition around the Urals (in Perm) also encountered success. A few Leningrad and Vladivostok residents who saw the exhibition in Perm asked us to show it in their cities, but we couldn’t guarantee security of the works or any type of certification. Hence, we vetoed the continuation of our exhibition’s voyage.

In Yeisk, Serge published the first mail art brochure in the U.S.S.R. (Fig. 61). This document included reproductions of Ruggero Maggi’s works with mail art by other artists. In the summer of 1990 we planned two important exhibitions: John Held Jr.’s (USA) stamp collection and the first international exhibition of visual poetry in the Soviet Union.

Figure 61. Serge Segay, Mail Art, Russia, 1989. Pamphlet.

All of these exhibitions and activities became possible with the advent of “glasnost.” Government agencies that previously incarcerated artists suddenly began signing release forms for the publication of posters. But these authorities didn’t necessarily love the art they once hated. In the USSR, government and art were altogether incompatible.

The KGB took great interest in mail art and began opening every one of our international letters. An unsophisticated-looking stamp, “Forwarded Damaged,” was placed on each of our torn and opened letters. Our letters took three to four months to arrive, disappeared by the dozens, or were returned without reason. Serge and I knew for some time that we were taking great risks with our art activities.

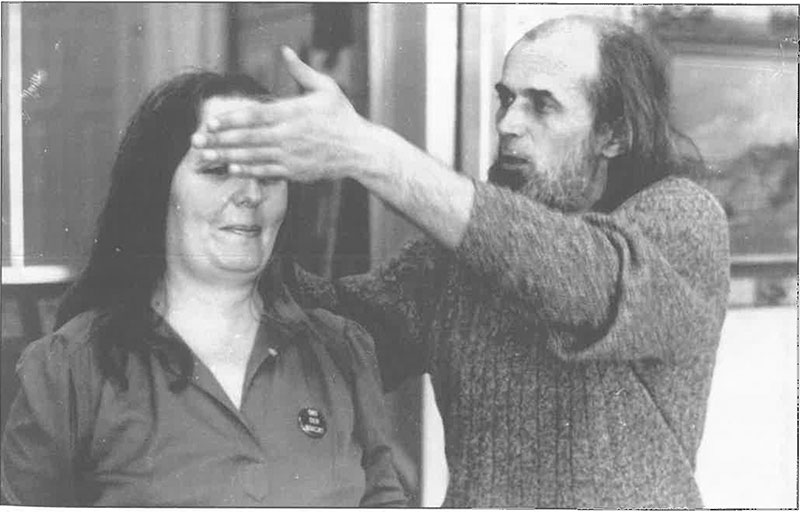

(Figures 62-63) When Serge and I went into mail art we were already active artists and poets. We had edited two samizdat[1] avant-garde journals, hundreds of unpublished books, collections, articles, textbooks, thousands of poems, paintings, drawings and unofficial poetic recitals for Leningrad audiences. We collaborated in the performance group, Transfuturists, (Nikonova, Segay, Konstrictor, Nik).

Figure 62. Rea Nikonova and Serge Segay, Spirit Netlink Performance, Russia, 1992. In collaboration with Crackerjack Kid, Nikonova and Segay organized a Russian Congress of the 1992 Netshaker Harmonic Divergence. The two hour event was held March 22 in the Yeisk Museum where activities included a music concert by American composer Janecek, a poetry reading, and an exhibition of bookworks by Chuck Welch, Miekal And, Liz Was, John Held Jr., and Craig Hill. Later, Nikonova wrote an account of the activities for the Moscow newspaper Humanitarian Fund.

Serge and I participated in unofficial art exhibitions in Leningrad and Sverdlovsk and edited a journal, Transponans. This publication was considered a model avant-garde journal in the nation and was the only journal which dealt with the subject of visual and action poetry in the USSR.

Transponans was published from 1979-1986 in a time now called “the era of stagnation.” Transponans was a risky, non-commercial venture that we distributed free. There were basic ideas of Transponans that sharply distinguished it from the sea of Soviet samizdat publications of that time. We strove towards originality in design; every issue had three formats, was handmade, and vaguely resembled an airplane with outstretched wings. Transponans was a theoretical elaboration of complex literary and pictorial constructions. The source of our publication could be traced to the early Russian avant-garde, a tradition largely unknown to many Soviet literary experts and nonconformist artists. The independent style of its editors brought Transponans a high reputation, even among its enemies.

Opponents to Transponans were not only from the conservative field (that of the realists, acmeists[2], absurdists, etc.—mostly from Leningrad), but also from the field of “innovators” or Moscow conceptualists, socialist artists and others. Residents of capitals, accustomed to patronizing the provincials, could not bear the thought that Transponans didn’t need patronage. The journal was already fit to supply ideas and information to anyone.

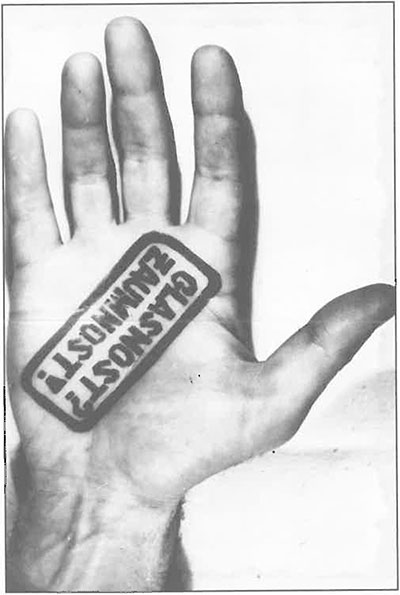

Figure 63. Serge Segay, Spirit Netlink Performance, Russia, 1992. A wet rubber-stamped “spirit impression” transferred by Serge Segay’s hand to Rea Nikonova’s forehead as pictured in Figure 62.

Serge’s long-standing interest in the Russian avant-garde gave readers of Transponans a lot of rare and valuable information. Publications were included in the journal and there were translations as well. One of the issues of Transponans included the manifestos of Michele Perfetti, Paulo Bruscky and others[3]. Separate, special issues of the periodical were dedicated to vacuum, pictorial and action poetry or to conceptualism. In the period of nine years, thirty-six issues were produced.

Glasnost completely destroyed many samizdat journals and triggered the creation of new ones. Many samizdat artists were somewhat at a loss because of the changes glasnost brought. Many irretrievably flung themselves through the opened doors of commercialism and some carried on with their usual work, unwanted by anyone and unable to find a new orientation.

Like many of the samizdat artists, Serge and I lost interest in continuing the production of Transponans. The journal had lost its aspect of risk, urgency and timeliness. Before glasnost, our publication was a dangerous venture that required large efforts to acquire art materials and technical tools for printing. Copier paper and paints, for instance, had to be shipped from Leningrad and Moscow. Still, glasnost brought to us the necessity of new ventures. Mail art became this venture!

At the height of glasnost, editors of Russia’s most prestigious fine art journal, Iskusstvo, offered its pages to the avant-gardists. It was because of this opening that a lengthy mail art story by Serge appeared in Iskusstvo’s tenth issue of 1989. Included were colored reproductions of mail art from the West. After the article appeared, many Soviet artists took an interest in mail art. Lithuania held two large-scale exhibitions, organized by Jonas Nekrasius[4]. Leningrad (St. Petersburg) and Sverdlovsk also planned mail art exhibitions[5].

Repressions? None whatsoever! Only a perpetual, irksome guardianship and an occasional roundup whenever you poked your nose too far. The guardians are ubiquitous—workers of the police muse who stretch out a cold paw of “fraternal” aid as they smile warmly with poisonous lips. They are everywhere: in the basements of “dissidents,” at embassy receptions, at meetings with “in-coming” foreigners. It is impossible to rid oneself of a sensation of binding “cooperation.” Serge’s and my war with the postal service has been a victory of sorts; receiving one letter instead of ten, five months after each letter is mailed. Our victory is the joy of discovering that our letters have reached the addressee. All of this would be humorous were it not so sad!

Only registered mail reaches the addressee from our province. But where can a Soviet person get money to send by registered mail? There is only one solution—to deny oneself everything: food, clothing, house repairs, celebrations, and more. In spite of all, the government functions like a gigantic concentration camp. One sends priceless letters beyond the border and some get through. Occasionally, we get an answer from the West with a Xerox copy of mail art show participants. We find our nation listed with a few participants. We realize that this slot for Soviet mail art was empty for a very long time and now, it is finally filled. In contrast to H.R. Fricker’s slogan encouraging “mail art tourism” is our enormous country, the motherland of mail art stillness. It seems to me that mail art in Russia has a future, but in the past it was directly lied to the politics of glasnost.

Serge and I live in the Krasnodar region—the Vandei of perestroika. Pluralism, glasnost and other hearths of life have not existed in our region. We live amidst the collective slaves who chew six letters of the only word, “Hurray!”

If no civil war or pogroms occur, if there isn’t famine, if everything is just the opposite and heaven on earth will come about, we will find paints, brushes, paper, and Xerox machines in our stores, the international mailing prices will be substantially lowered, the free market will provide a few Western art magazines, the art exhibitions taking place mostly in Moscow will be shown on television, and the capital won’t be mere sites for the sale of paintings. If all of this happens, then I see the future of Russian mail art in merry colors.

The Russian people are communicative. Among other things, they will quickly learn English when it is truly allowed; when dictionaries are available in our stores we will be happy! One can only hope to stay alive until these heavenly times arrive. With pride we will continue to send our invitations to visual poets of the world for an international exhibition of visual poetry at Yeisk. Without waiting for the heavenly conditions to arrive. Serge and I continue working under difficult conditions, for we realize that art continues against all obstacles.

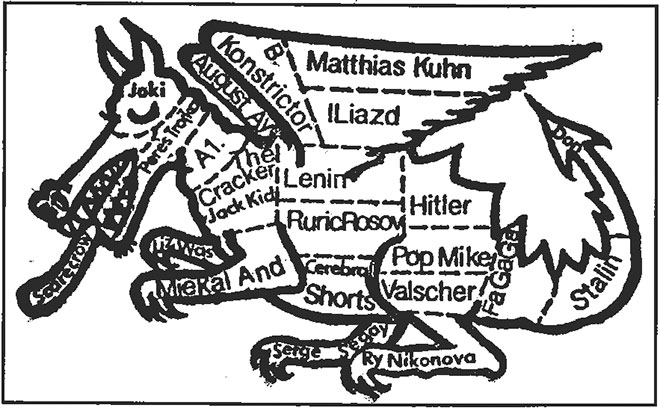

Figure 64. David Jarvis, Serge Segay and Rea Nikonova. Soviet Mail Art Dragon, 1989. Rubber Stamp.

________________________

[1] Samizdat is a form of free existence, without censors, of Russian art from the 1960s to the 1980s. Poets often used typewriters to create small editions of five to forty copies for themselves and friends. The authorities repressed anybody making or reading these books.” (Quotation from Rea Nikonova in a letter to Chuck Welch dated October 5, 1990).

[2] Acmeists were a group of Russian poets from the early twentieth century whose work closely resembled realism and romanticism. Members included the famous Russian poets Anna Achmatova, Osip Mandelstam, and Nicolaj Gumilev. The Acmeists have many imitators in Leningrad today largely because of the inlluence of Anna Achmatova who lived many years.” (Ibid.).

[3] Michele Perfetti and Paulo Bruscky: Perfetti is an Italian performance artist and pioneering mail artist who organized many visual poetry shows and publications. Paulo Bruscky is a Brazilian visual poet and mail artist who, with Daniel Santiago, organized the government censored International Exhibition of Mail Art in Recife, Brazil, August 1976. Serge Segay, upon finding Perfetti and Bruscky’ s manifestos in the Polish magazine Stucka, translated their texts for the Russian avant-garde journal Transponans.

[4] Nekrasius Jonas from Lietuvos, TSR organized two mail art exhibitions. The Windmill, October 28, 1989-February 28, 1990, and The Bridges held in Pakruojis, Lithuania from May to October 1990. In November 1990, Jonas, in collaboration with Italian Bruno Chiarlone, was organizing a third mail art exhibition with a theme of “Lithuanian Independence.”

[5] I read in Sverdlovsk’s newspaper about a mail art project there entitled My God. Serge Segay and I had planned a mail art show for Leningrad (St. Petersburg), but the KGB took our initiative into their own hands and we refused to pursue the idea any further.