Pawel Petasz: Mailed Art in Poland

Petasz, Pawel: Mailed Art in Poland, in: Eternal Network. A Mail Art Anthology, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, 1995, pp. 89–93. (Ed. by Chuck Welch)

Before the term “mail art” came to be known in Poland as the name of an international communication genre, there were conceptual Polish artists such as Anastazy Wisniewski, Leszek Przyjemski, Zofia Kulik, Przemyslaw Kwiek and Andrzej Partum(1) who were working during the 1960s and early 1970s. These artists and others were active in many creative genres including PhotoMedium and Contextual art(2). What differentiated these mail exchanges from western mail art was twofold: first, Polish mail art exchanges were primarily in-country, and second, the major purpose of these exchanges was to create art that challenged or circumvented the restrictive ideology and regulations of the Polish people’s art scene. The marginal character of these postal exchanges was balanced between an unofficial or illegal status. Furthermore, the concepts and purposes for Polish mail art exchanges were privately shared and understood from a localized Polish perspective(3)

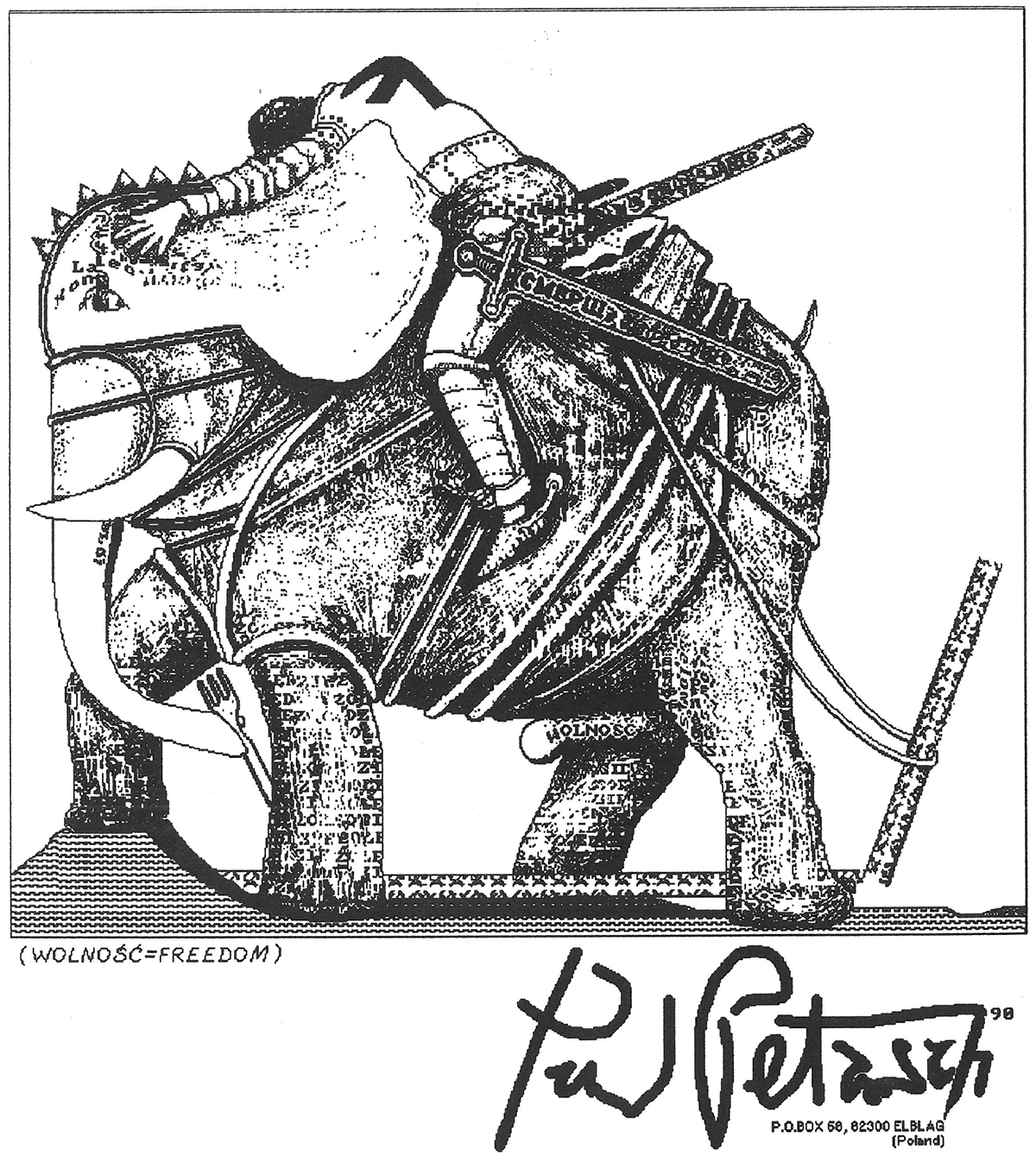

Figure 57. Pawel Petasz, Freedom, Poland, 1990. Computer Print

Figure 57. Pawel Petasz, Freedom, Poland, 1990. Computer Print

Under Communist rule, all duplicating and printing services were strictly controlled and not available for private or public usage. Student galleries and local cultural centers, however, were not censored as severely and often became a conduit for the exchange of independent texts— concrete and visual poetry, scripts or edited documentation. Quite often, a show or an event scheduled by a local art center would be a pretext for printing and distributing material that would otherwise be severely censored. A local gallery could not obtain a censor’s permission to print books, but they were allowed to print show catalogues in editions of 100 copies. The content of these programs or catalogues had to be passed with a censor present, but such visitations were more relaxed and discussion could be bargained over a vodka. Readers may find it hard to imagine mature people playing such silly games with words and compromises, and so an anecdote may help to illustrate the spirit of these times.

In 1974, I was appointed director of a municipal art center in Elblag. I decided to mail out an art calendar for the art center which would double as an announcement of my new position there. I made a paste-up for the calendar, and the art center applied for permission to create it(4). On the first visit, the censor found the calendar ineligible for discussion. It was argued that the calendar and not the art would have to be discussed by a top authority. I decided to remake the paste-up into a fake show poster with room enough at the top of the poster to be cut off so the word “calendar” could be added later with a rubber stamp. Not having a clearly established date for the calendar, I had to simply print, “In December.” But the censors didn’t like my usage of “December” because that month was associated with worker protests in Gdansk in 1970. They forced me to use the number 12 in place of December. I had to reconstruct the calendar a third time because the photograph of our art center, now located in a reconstructed former church, revealed a small cross visible on the back roof. I agreed to paint a cloud over the cross. Eventually, my calendar was printed, but with a variety of material collaged to conceal visual information I never intended to be interpreted as signifiers of anti-state content. For example, there was a snapshot of a prominent slogan, “We Are Building Our Fair Future,” that was placed over heavily barred windows. The censor didn’t understand my collage and for the price of removing a cross from my work, my calendar was printed and the intended subversive content remained.

I learned about mail art accidentally in 1975(5). It was very exciting to suddenly have a chance to participate in a world in which the Iron Curtain didn’t exist. All mail restrictions in Poland were shamefully hidden from the people. Oddly, unlike most Communistic changes to Poland, there was never any “People’s Post” introduced in Poland. The general postal regulations continued unchanged from the refreshingly cosmopolitan, open years of the 1930s. Problems began to occur when government spy hunters infiltrated the postal system, where they remained in the background of everything until the Spring of 1989. In the 1970s it wasn’t a crime to receive letters from abroad, but if you received too many, a logical excuse was needed.(6)

In the late 1970s, government spy hunters visited me several times. Since I wasn’t considered dangerous, these visits were friendly ones and a bottle of vodka was brought along to be shared with me. Politely, the intelligence agents would ask me to make a friendly gift of a valuable book or record that might be in sight. On one visitation, I was told by the intelligentsia to leave my studio and go after something. I don’t know what they wanted to do or why they asked me to leave, but I suspect they were going to “bug” my studio, although upon returning I searched and found no listening devices. My next studio was never officially searched, although I once found my cat outside the studio after I’d left it inside.

I tried to appear ignorant of any wrongdoing. I would try to cover up any suspicious mail, “corrected” works, or tried omitting any real Polish underground contacts. I avoided underground contacts because I didn’t want to have anything to tell the authorities, no matter how they tried to induce “cooperation.” But there was another reason, on the margin, that most of the underground activity was merely a provocation. The authorities would often instigate trouble for the sake of keeping their jobs. They would fabricate reports, closed cases, etc. I will not elaborate on the matter here, but Communism didn’t die in Poland because some underground fought it. The state was so omnipotent and present in everything that the real underground, real secret activity, was almost impossible. It was always either inspired or kept by security police, as a farmer keeps pigs at his farm, feeds them, lets them reproduce and kills one from time to time.

Repression in Poland, as compared to Chile or Russia, was never especially severe. Still, oppression in Poland was present everywhere in the form of a grey, hopeless reality with no place to move or do as one wished. Instead, there were limitations on our consumption and cultural freedom accompanied by overwhelming propaganda; that, “Men—this is it, the working class paradise, and it is going to be a greater paradise very soon!” Everything in our culture was upside down, white was black, and while you knew this wasn’t true, the TV, newspapers, and slogans left no escape; white IS black! This was the horror!

Visits by spy hunters ceased in the 1980s, although in 1985 I was called to visit the secret police headquarters, where I was offered a passport if I would accept a position as an agent. I began to suspect that a center for mail art investigations were being run by the intelligentsia in my hometown, Elblag. This suspicion is based on several facts. Twice I found correspondence from other Polish mail artists addressed to other, far-away towns mixed incorrectly with my own post office box mail. Another time I was called to the militia station and confronted with a large pack of my recent mailings. They informed me that my mail had been stolen from the post office and rescued during a search at a suspect’s home. I was to sign for the mail stating that I recognized the letters as my own correspondence. They let me have some of the “stolen” mail but kept the rest as proof against the criminal. This encounter was my closest brush with conviction by the authorities.

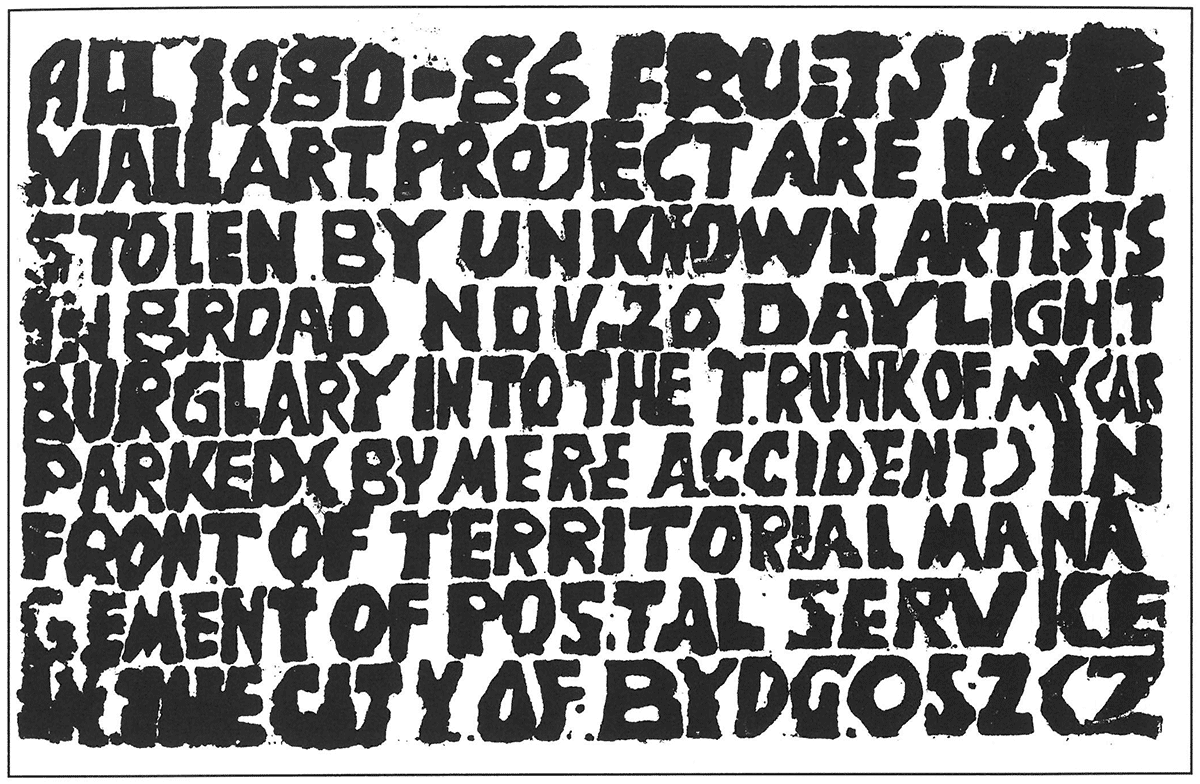

Figure 58. Pawel Petasz, Untitled, Poland, 1987. Rubber-stamped message. The notice above appeared inside an envelope addressed to the editor. Petasz folded and sealed the envelope on three sides with machine stitching.

Figure 58. Pawel Petasz, Untitled, Poland, 1987. Rubber-stamped message. The notice above appeared inside an envelope addressed to the editor. Petasz folded and sealed the envelope on three sides with machine stitching.

After the martial law issued by former President Jaruzelski, it became obvious to the Polish people that they couldn’t live under Communism any longer. Communists could no longer lie to us about a bright, happy, future in which their propaganda was portrayed as a lesser evil compared to the Soviet Union. It was no longer a crime to express discontent with Communism, as long as it wasn’t a conspiracy. Still, the possession of a typewriter and a few leaflets was enough to arouse suspicion. The militarized post offices were instructed to pay attention to the “language of stamps”(7) and demanded that recycled envelopes must not be mailed abroad because recycling parodied the poor economic situation within Poland. In the beginning of martial law, letters were to remain open and always received a rubber stamped impression which read “censored” or “not censored.”

The overbearing authority of the postal service exploited the people, and mail theft was common. There were methods used to break up communication between senders and recipients by failing to deliver correspondence. My mail was being constantly checked, and it was customary to find everything sorted and bundled by country; one day the mail would arrive exclusively from East Block countries, next day, the USA. The envelopes, which were torn open, were usually placed in sealed plastic bags rubber-stamped “received damaged.” Robbery was common, as investigators frequently searched foreign mail for money or valuable items. Such mail was purposely delayed, or the delivery was so uncertain that any crimes committed were impossible to ascertain. The international Commonpress(8) collaborations, which I started in 1978, were impossible to coordinate because of constant postal interference.

I had no control over anything I mailed or received by post, but after the martial law controls were suspended I would either fold or sew my handmade paper envelopes with a sewing machine. The sewn mail was very difficult to open or unfold for photocopying by censors. The ostentatious appearance of these envelopes was provocative, yet this mail usually passed through. Using a variety of handmade paper, I purposely kept all of my mailings thick and coarse in appearance. The strategy proved successful for several years. When I needed to mail something that couldn’t be included in the sewn envelopes, the material was nearly always lost, registered or not.

Mail art was never respected by the official artists and art critics of Poland(9). The number of mail artists were always small, fewer than twenty, and primarily included H. Bzdok, T. Schulz, A. Dudek-Durer, R. Rupocinski, A. Dudek, A. Kirko, W. Ropiecki, and P. Rogalski. The mail art network was useful, however, as one of many information holes punched through the Iron Curtain. Mail art itself probably had little effect in breaking down Communist oppression. In a larger sense, however, mail art helped to free Polish artists from a feeling of rejection by others in the world.

At present, there are problems that have dampened my optimism that Polish artists will once again be global citizens in the arts. In December 1988, Piotr Rogalski organized a mail art show for a popular teenage newsstand magazine, Moj Swiat. The article encouraged an overflow of mail art exchanges within Poland, but the interest arrived too late. Poland’s tragic economic inflation

continually increases postal rates, and it is unlikely that the mail art fad can be sustained under these conditions. Furthermore, there isn’t evidence of any clear ideology that is being expressed by artists within Poland. We have been accustomed to fight against, and not for. What shall we fight for? Wealth? Yes, we want wealth, but to want it is a shame in the modern tradition. Shall the alternative art cry resound for wealth when it is supposed to fight for the survival of elephants and whales? There is no conclusion to our situation in Poland. Everything is in rapid transition, and nothing makes any sense. While mail art in Poland has helped us to break the feeling of past rejection by the world, our future remains uncertain, as do mail art activities that may help us evolve in a positive direction of involvement and influence in the world today.

(1) Wisniewski, Przyjemski, Kulik, Kwiek and Partum were Polish artists whose activities involved some mailing strategies, but which were never designated by each artist as “mail art.” Anastazy Wisniewski was active in performance art, environmental art, and bookworks. Wisniewski often presented Communist rituals, celebrations, decorations, slogans and documents in an absurd, hidden context. Leszek Przyjemski, originally from Anastazy Wisniewski’s group, later developed concepts into an international character, e.g. The Museum of Hysterics. Zofia Kulik and Przemyslaw Kwiek tried to organize a variety of alternative art events within Poland and succeeded in forming an unofficial art center, The Workshop of Art Creation, Distribution and Documentation. Both Kulik and Kwiek referred to their mailing activities as “Rozsylki,” to send, spread out messages. Andrzej Partum, concrete poet, editor and organizer of independent art events, also carefully omitted the mail-art label from his work. (Brief references to these Polish artists and their activities were given by Pawel Petasz in a letter to Chuck Welch dated October, 1990.)

(2) PhotoMedium Art is performance-connected photography with a conceptual-sociological background. Oftentimes, PhotoMedium artists used snapshots and film and presented them in a non- documented series that looked somewhat like Muybridge’s pioneering photographs of people and animals frozen in motion. (Definitions as described in a letter to Chuck Welch from Pawel Petasz.) Contextual Art is sometimes referred to in Poland as “meta sztuka” or “meta-art.” The terms apply to intellectuals or art critics who declare their theoretical art texts to be an artform. These didactic texts were generally self-edited and self-distributed by mail. Pawel Petasz stated, “This was a very nice idea, but a bit boring and so these theoreticians created ‘contextual art’ so that anything could be art or not, depending on a context or situation.” (Pawel Petasz in a letter to Chuck Welch dated October 1990).

(3) For readers interested in pursuing further information about contemporary art and artists in Poland write to Centrum Sztuki Wspolczesnej (Contemporary Art Center), Director, Zamek Ujazdowski, Aleje Ujazdowskie 6, Warsaw, Poland. Or write to SASI (Other Artists Association), P.O. Box 2, 05092 Komianki, Poland. There are many texts pertaining to contemporary Polish art, but the editions are usually small and sometimes difficult to locate.

(4) In the case of calendars, a letter of permission was required for approval from the main censor’s office. The procedure was that you had to go to a printer with an official letter of commission from an institution and not an individual. The censor’s letter of permission would describe in detail the printing job and number of copies allowed. After the copy paste-up, the censor would rubber stamp approval on the back of each page. This procedure was possibly followed to prevent the designation of forbidden anniversaries, cancelled holidays, etc.

(5) I have a catalogue for a Polish mail art show organized in 1974 by the West German mail artist and neo-Dadaist Klaus Groh. The small, gallery mail art show was entitled. The Exhibition of the INFO group.

(6) In the early 1950s, receiving letters from abroad was a crime.

(7) Although this surprised me, I recall reading in a Sunday paper that such strategies did exist as something between semaphore alphabet and lovers’ code: a stamp in the right comer equals “I love you.”

(8) Note by Chuck Welch: Commonpress Magazine, a democratic, open forum founded in December, 1977. Commonpress encouraged an open, “floating” editorship to anyone assuming responsibility to print and distribute copies.

(9) Mail art was never respected in Poland. This is a fact that could be attributed to the simple context in which mail is regarded. The Polish language doesn’t tolerate common words for uncommon activities. Mail is too simple, Art isn’t. In Polish, for example, a record player could be simply expressed as “nagrywacz,” but this is too simple a word for such a complicated device. So there are words taken from other cultures, like “magnetofon,” “gramofon” or “magnetowid,” although these words are not used in this meaning there. In a more complicated, serious tone, a producer would call it something better: “urzadzenie magnetofonowe” (a magnetofon device). “Mail art?” This doesn’t sound serious at all!