John Held Jr: The Sugar-Coated Bullets of Pawel Petasz

Held, John Jr.: The Sugar Coated Bullets of Pawel Petasz, in: Pawel Petasz: Arriere Garde, Stamp Art Gallery, San Francisco, USA, 1996

In the mid to late seventies mail art began reaching out across the world, and there were many active network artists from different cultures expressing their inward sentiments and outward conditions in various fashions. Some of the most interesting work arrived from artists in latin America and Eastern Europe living under repressive social and political restrictions. The art reflected the reality.

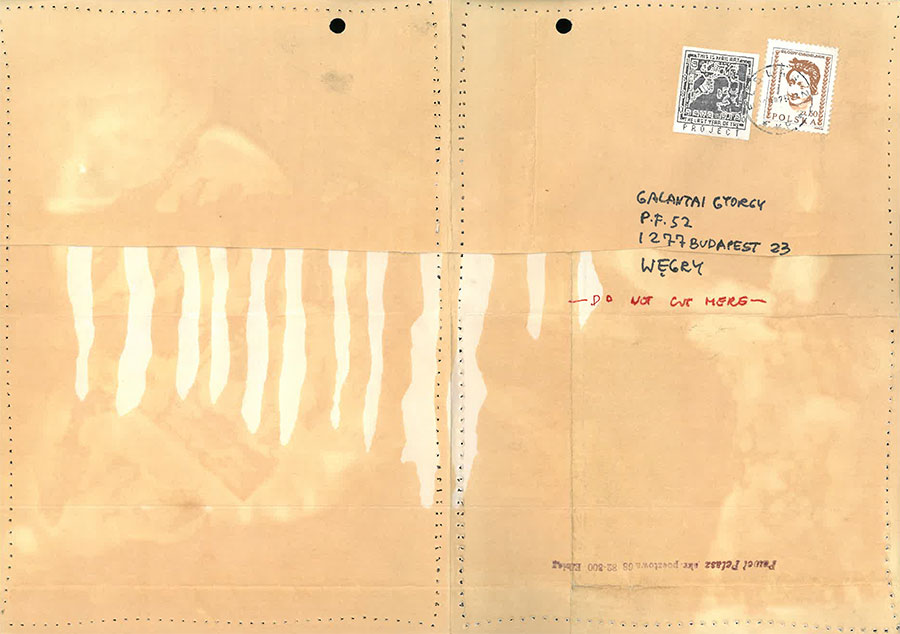

No work was more anticipated in one's mailbox during this period than that of the artist Pawel Petasz from Elblag, Poland. In order to confound the censors in his country, he would sew his envelopes shut. As a result, it became immediately apparent if his letters were tampered with. To receive a letter from Pawel Petasz, no matter what the content, was an event. There was a sense of direct involvement in an international conspiracy of goodwill in opposition to the old international order fostering division among a global brotherhood.

Artists took these bold steps for different reasons. Petasz was never an overtly defiant renegade in Communist controlled Poland. He was an artist with a need to reach out to other artists. This simple act branded him as one to be watched and controlled.

"In the late 1970s, government spy hunters visited me several times. Since I wasn't considered dangerous, these visits were friendly ones and a bottle of vodka was brought along to be shared with me. Politely, the intelligence agents would ask me to make a friendly gift of a valuable book or record that might be in sight. On one visitation, I was told by the intelligentsia to leave my studio and go after something. I don't know what they wanted to do or why they asked me to leave, but I suspect they were going to 'bug' my studio, although upon returning I searched and found no listening devices. My next studio was never officially searched, although I once found my cat outside the studio after I'd left it inside."[1]

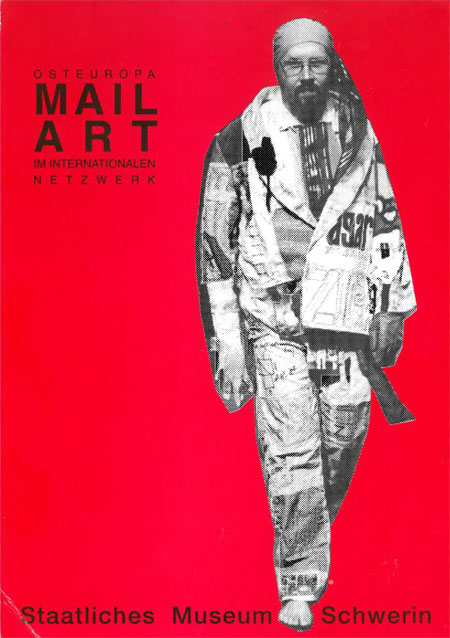

He was joined by other Polish and Eastern European artists in his desire to communicate with the outside world, but his patient devotion to the mail art network and unique creativity made him a seminal figure in Eastern European alternative artistic circles. When the Staatliches Museum Schwerin published a catalog of their 1996 exhibition, Eastern European Mail Art in the International Network, they placed Petasz on the cover.

Striding barefoot in a sea of red ink, the black and white figure of Petasz marches across the book cover in a wardrobe composed of artworks on cloth sent to him by mail artists from around the world in response to a mail art project he instigated at the behest of the Stempelplaats Gallery in Amsterdam, Holland, in 1980. He called this project, The Intellectual Benefits of Art.[2]

This action typifies Petasz's desire to link art and life, using the postal system as a means of connecting diverse individuals around the world, and using these contacts to initiate other actions, such as his march through the streets of Amsterdam.

Mail art was of utmost importance to Petasz; like food, clothing and shelter. It protected him from the isolation of a closed state, providing him some measure of hope. His experimental actions in the face of unpredictable state action set an example for others in more comfortable circumstances, setting a standard for others to measure themselves against.

The isolation of Poland after WW II was fertile ground for a response by artists from the alternative cultural scene. In 1971, conceptual artist Jarosław Kozłowski and critic Andrej Kostołowski circulated a statement to artists connected with alternative artistic centers in small and large cities around the country[3]. Although not mentioning mail art by name, the strategies they put forth related to the practice of Fluxus artists and the emerging philosophy of the correspondence art network.

"THE NET

-THE NET exists outside institutions;

-it includes private homes, artists' studios, and other places where artistic proposals are born;

-the proposals are directed to those interested;

-they are accompanied by publications, the form of which is quite arbitrary.

THE NET has no central point, and no co-ordination;

-the knots of the net are located in various cities and countries;

-the contact between the different knots is carried into effect through an exchange of concepts, projects, notations and other methods of articulation, as a result of which parallel presentation at all points is possible;

-the idea of the NET is not new; once it has surfaced, no author can be indicated;

-THE NET may be used and reproduced at will."[4]

Petasz writes about the beginning of his own involvement in mail art, occurring in the the mid-seventies; the start of a journey that would make him one of the most beloved figures in the network.

"Repression in Poland, as compared to Chile or Russia was never especially severe. Still, oppression in Poland was present everywhere in the form of a grey, hopeless reality with no place to move or do as one wished. Instead, there were limitations on our consumption and cultural freedom accompanied by overwhelming propaganda; that, 'Men-this is it, the working class paradise, and it is going to be a greater paradise very soon!' Everything in our culture was upside down, white was black, and while you knew this wasn't true, the TV, newspapers, and slogans left no escape; white IS black! This was the horror.

I learned about mail art accidentally in 1975. It was very exciting to suddenly have a chance to participate in a world in which the Iron Curtain didn't exist. All mail restrictions in Poland were shamefully hidden from the people. Oddly, unlike most Communistic changes to Poland, there was never any 'People's Post' introduced in Poland. The general postal regulations continued unchanged from the refreshingly cosmopolitan, open years of the 1930s. Problems began to occur when government spy hunters infiltrated the postal system, where they remained in the background of everything until the Spring of 1989. In the 1970s it wasn't a crime to receive letters from abroad, but if you received too many, a logical excuse was needed.

I tried to appear ignorant of any wrongdoing. I would try to cover up any suspicious mail, 'corrected' works, or tried omitting any real Polish underground contacts. I avoided underground contacts because I didn't want to have anything to tell the authorities, no matter how they tried to induce 'cooperation'. But there was another reason, on the margin, that most of the underground activity was merely a provocation. The authorities would often instigate trouble for the sake of keeping their jobs. They would fabricate reports, closed cases, etc.. I will not elaborate on the matter here, but Communism didn't die in Poland because some underground fought it. The state was so omnipotent and present in everything that the real underground, real secret activity, was almost impossible. It was always either inspired or kept by secret security police, as a farmer keeps pigs at his farm, feeds them, lets them reproduce and kills one from time to time.

I had no control over anything I mailed or received by post, but after the martial law controls were suspended I would either fold or sew my handmade paper envelopes with a sewing machine. The sewn mail was very difficult to open or unfold for photocopying by censors. The ostentatious appearance of these envelopes was provocative, yet this mail usually passed through. Using a variety of handmade paper, I purposely kept all of my mailing thick and coarse in appearance. The strategy proved successful for several years. When I needed to mail something that couldn't be included in the sewn envelopes, the material was nearly always lost, registered or not...

Mail art was never respected by the official artists and art critics of Poland. The number of mail artists were always small fewer than twenty...The mail art network was useful, however, as one of the many information holes punched through the Iron curtain. mail art itself probably had little effect in breaking down Communist oppression. In a larger sense, however, mail art helped to free Polish artists form a feeling of rejection by others in the world."[5]

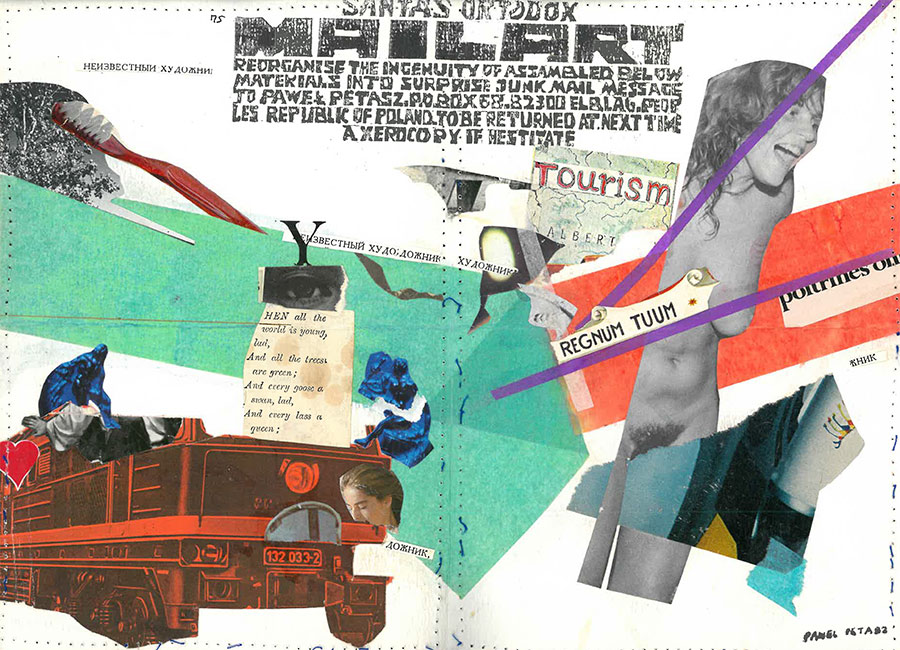

Petasz was active on many fronts of alternative creativity. Rubber stamp art, performance, artists' books, organization of mail art shows, and publications were but a few of his interests.

That he was able to participate in the growing popularity of rubber stamps in the mail art network, is itself a poignant tale. Rubber stamps were tightly controlled in Communist countries, because of the potential they carried for bureaucratic havoc. Internal passports were vital documents in controlling the population, and rubber stamps played a key role in the authority they carried. Rubber stamp use by individuals was prohibited, and those used by institutions were closely guarded. At night, rubber stamps used by schools, state agencies, banks and other offices, were locked in special safes constructed for this purpose.

To overcome these obstacles, Petasz began to carve his stamps from erasers. The homegrown feel of these stamps, gave Petasz's works much of their charm. It was in part because of his activities eraser carving has become such a popular mail art activity. This is just one of the many areas where Eastern European artists, deprived of the freedoms taken for granted in the West, were able to contribute their special brand of creativity throughout the network.

Hungarian writer and mail artist, Geza Perneczky has written of Petasz's rubber stamp activity in his work, The Magazine Network. He likens the rubber stamp works to conditions under which Petasz was forced to operate.

"In the years between 1975 and 1978, Petasz depicted figurative motifs, or occasionally complete scenes or multi-figural compositions in his rubber stamps. In his small-format pictures, Petasz managed to turn the generally grotesque humour of the Poles into a kind of bitter histrionics, as if he had studied his art from the drawings of Goya. His oeuvre was only enriched when he chose to crush his painstakingly carved stamps in order to replace the expressive prints with splinter impressions. These fragments gave a tragic tone to Petasz's message, which blended personal doom with a sense of national mourning. The tragic darkness of the stamps created by Petasz can be likened only to that of the prints of some Latin American artists, notwithstanding that Petasz lacked the crystallized formal discipline of the latter. Accordingly, this affinity must not be established without reservations. I would say that the rubber stamps of Pavel Petasz, which reflect the helter-skelter dash towards suicide, have no rival in the world.

It would be a rather difficult task to systemize Petasz's stamp art publications. This much is certain that he launched his International Magazine of Rubberstamped Art sometime in 1978 or 1979. The majority of these publications were 'lettuce-like' compositions, since Petasz used glue and stapler to compile artworks from the postmarked corners of his mail. Accordingly, the term 'magazine' can hardly be applied to these unique works of art. Petasz's other series of publications, entitled Obsolete Rubberstamps, was a shade more distinct (and perhaps also more coherent). He used his shattered stamps to produce this series, and each issue had an unusual size. The number of copies ranged from 13 through 30+3 to 39, and this formal confusion can easily be identified with the puzzling contents."[6]

Petasz was the creator of many publications, none more influential then his Commonpress[7] project, arguably, one of the most conceptually important projects ever undertaken in the mail art network.

In 1984, the Belgian art administrator Guy Bleus undertook the documentation[8] of the Commonpress project, and had this to say about it's origins:

"CP is not a 'common' art-magazine. It is a special one, because it is 'common'. Created, produced and distributed by and to its participants each edition has a different editor. This almost seven years young artists-magazine has its own origin and evolution. The father and motor of CP is the Polish artist Pawel Petasz, who started this new art-medium, this remarkable art-forum and art-form in December 1977 (publication of the first edition). The short history of the magazine is closely related to the fast development of Mail-Art as a global movement. As the first threads of the Mail-Art-Web, CP started small. But this international small-press magazine with only 17 participants in the first edition had a solid concept. One can read in the first issues the participating rules which e. g. 'obliged' every contributor to print and distribute an edition once. This sounds severe, but is was a democratic principle, necessary for the survival of the alternative magazine and not insuperable to fix with only a decade of participating artists.

The succession of the different editions passed off quickly: almost sixty planned editions in seven years. But personal and social complications sometimes hampered the publications. Some artists with personal problems could not edit the planned issue yet. Besides there was (and is) the enormous growth of the number of contributors to each edition which increases the problems of financing and sponsorship.

On the other hand the sinister political climate in Poland in 1981 (with military censorship of the mail) obliged Pawel Petasz to transfer the coordination of CP to Gerald X. Jupitter-Larsen in Canada."[9]

Petasz was the organizer of many projects, beginning in 1977 when he presented his Christmas Show, featuring the work of thirty participants. That same year he initiated an even larger project, Circle '77, held at the Uniart Gallery in Elblag, attracting the participation of some one-hundred and seventy two artists form around the world.

In 1978, he curated the Transparent Art Show, composed of slides from thirty-eight participants. In 1979 he organized two exhibitions, Elblag Spring Salon and Five Collective Pictures for Competitions. During the eighties Petasz worked on two long running projects, This is Mail Art and This is I(AIL) Art, both of which were exhibited at De Media in Eeklo, Belgium, in 1991.

Another important action of his was the exhibition Square 88, one of the first exhibitions of art by computer in the mail art network. This exhibition at the Centrum Sztuki, Elblag, marked the beginnings of Petasz's work on the computer, which occupies him to this day.

Petasz's computer artworks often display symbols of Communism mixed with old woodcuts, drawings, printed cartoons, dictionary definitions, and other iconography drawn from a variety of sources, which are then scanned into the computer and collaged. Text and visual imagery are intermixed, linking this newer work to his early rubber stamp experiments in visual poetry.

For his exhibition at The Stamp Art Gallery, he has impressed his old rubber stamps of the seventies over the computer works, fusing two of his major interests. Colors have been added by rubber stamping, colored pencil and watercolor.

In one work, Sugar-Coated Bullets (1996), he writes that the "snapshot" includes;

"1) The Main Street in Elblag. 2) Hand-cut rubberstamps of '70s in a digital shape. 3) Pawel Petasz in Moscow, that is a place especially dear for American hearts, even if cold, unfriendly and ugly."

These "sugar-coated bullets" remind one of Petasz's former musings on the role of the secret police in Poland under Communism.

Everything in our culture was turned upside down, white was black, and while you knew this wasn't true, the TV, newspapers, and slogans left no escape; white IS black! This was the horror!

And now that the secret police and double-speak have vanished, other obstacles present themselves - primarily financial. Petasz describes himself as, "a free lance visual artist and designer, simultaneously wasting his time and benefits for marginal and ephemeral vanguard art genres. A country pioneer of computer graphics and collage, never able to (go) forward." Despair never seems far from Petasz's thoughts ("the generally grotesque humour of the Poles," as Perneczky cites the condition), yet his personal creative drive continues to inspire others throughout the world.

_______________________________

[1] Petasz, Pawel: Mailed Art in Poland, in: Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Canada, 1995, p. 89—93.

[2] See the documentation of Petasz’s project Intellectual Benefits of Art (Editor’s note)

[3] The 1972 version we published here is slightly different compared to the version published by Held. (Editor’s note)

[4] Rypson, Piotr: Mail Art in Poland, in: Osteuropa Mail Art im Internationalen Netzwerk, Staatliches Museum Schwerin, Schwerin Germany, 1996, p. 87.

[5] Petasz, Pawel: Mailed Art in Poland, in: Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Canada, 1995, p. 89—93.

[6] Perneczky, Géza: The Magazine Network: the Trends of Alternative Art in the Light of their Periodicals 1968-1988, Soft Geometry Edition, Köln, Germany, 1993, P. 87.

[7] See the magazine in our Chro-no-logy. (Editor’s note)

[8] Bleus, Guy: What is Commonpress?, in: Commonpress No. 56. Commonpress Retrospective, Administration Center, Wellen, Belgium - Museum het Toreke, Tienen, Belgium, September, 1984, pp. 106–108.

[9] See the documentation (Editor’s note)